The Experience of Distance Learners as Writers

Phil Wood, Bishop Grosseteste University, Palitha Edirisingha, University of Leicester, United Kingdom

Summary

In 2016, we (Edirisingha & Wood, 2018) attempted to develop provision for distance learners on an MA in International Education through the use of a modified version of lesson study, an approach affording the opportunity to consider student learning and practice development (Wood & Cajkler, 2016). One area of student need which became clear in this work was the difficulties experienced by some students in relation to academic writing. Being remote from support, relying heavily on electronic resources with little access to extra support which those on campus-based programmes take for granted, we decided carryout this initial investigation to understand the experiences of these learners as academic writers working at a distance.

Introduction

Whilst distance learning has become an established field of research for practice development, there is relatively little research focusing on the experiences and approaches to writing undertaken by students. Academic writing is the focus of a very large literature, but this predominantly focuses on grammar and structure of writing, as in the English as Academic Practice (de Chazal, 2014), and the emotional impact of the writing process (Huerta, Goodson, Beigi, & Chlup, 2017) rather than understanding the processes utilised by students when writing for assessment purposes.

We were interested in exploring the following questions to focus a preliminary investigation into some of these issues:

- What is the role of technology in the process of academic writing for distance learners?

- How do distance learners approach academic writing as a process?

- What forms of support are used by distance learning students to support their writing?

The programmes we focused on were to masters level programmes in an education department at a UK university. The majority of students were full-time teachers and academics undertaking the programmes whilst in full-time employment.

Methodology

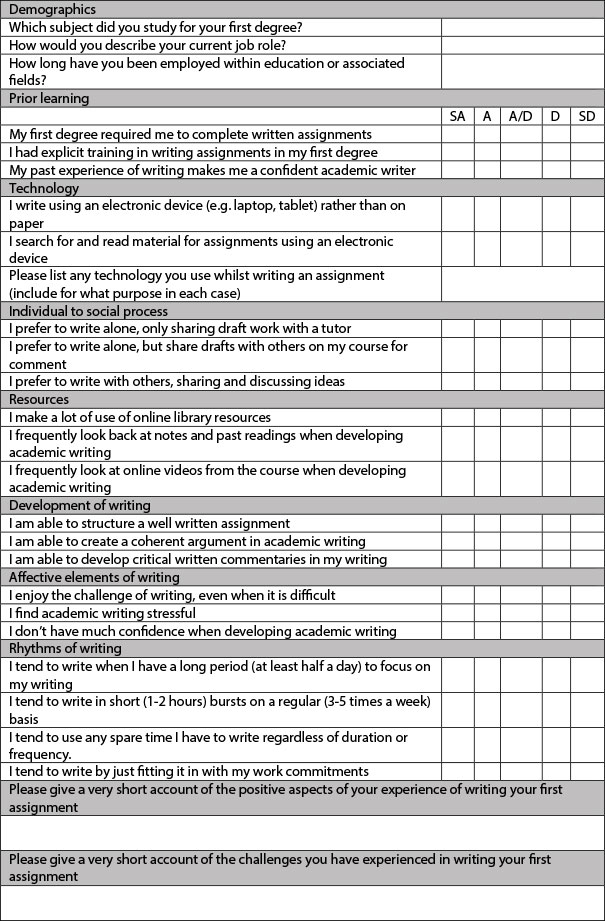

To carry out an initial exploration of student experiences of writing, a simple explanatory mixed methods approach was used during the winter of 2017. After obtaining ethics approval from the university ethics committee, all students on an MA in International Education (n = 50) and those on a Post Graduate Certificate in Educational Technologies (n = 17) were e-mailed a link to an online questionnaire (Table 1 shows the questionnaire items) together with an invitation to take part in the study and were asked to complete it if they wished. The questionnaire was wholly optional, and it was made clear to students that its (lack of) completion was not linked in any way to their work on the course. Students were asked to include their e-mail address if they were willing to be interviewed online subsequent to completing the questionnaire. In the questionnaire students There were 28 returns (response rate = 42%). Based on an initial analysis of these returns, a set of interview questions (Appendix 2) were developed. The interview text was sent out as an e-mail to complete as an online interview (James & Busher, 2009). Due to time restrictions and the period over which the returns were made it was not possible to send out follow-up questions in a second round of questioning as would normally occur in the online approach to interviewing.

The data were collated for simple descriptive analysis in the case of the questionnaire data, and the interview data were analysed using emergent coding to create a set of basic themes from the data.

Questionnaire Findings

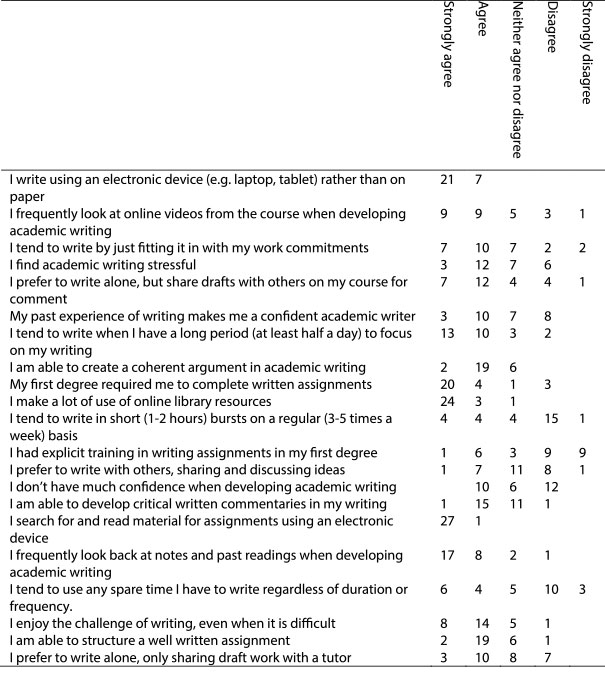

The summary of the results from the Likert Scale items of the questionnaire are shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Summary results from questionnaire focusing on the experience of distance learners in relation to writing

The results from the questionnaire show that there is a ubiquitous use of technology in the assignment writing process. Students identified that they tend to make more use of tablets, particularly iPads (students on the MA International Education programme are given a complementary iPad when they start the course), for searching for literature and reading that literature once found. This appears to extend to reading on screen rather than downloading and printing off papers for analysis. However, whilst the portability of tablet computers for searching and reading are highlighted, when it comes to writing, there is a greater tendency to use laptop computers. Some students also mention particular Apps at this point, with five students identifying that they hold written drafts on Google-Docs, and 4 students identifying their use of Grammarly for checking and ensuring a good quality of written academic English.

Time is also an issue which appears to be important for students in their writing experiences. Most identify a preference for writing alone, perhaps unsurprising for a distance-learning medium, although a small number of students do state in answers to the later, open questions in the questionnaire that they have found informal collaboration has been a useful part of their work, an observation which is duplicated in the subsequent interview returns. Working alone appears to be an important aspect of their writing experience as many of the respondents identify a need to fit their academic writing around their professional responsibilities meaning that they create personalised rhythms for their writing process. This also means that they are often having to find time in-between other activities. This may lead to a less satisfying experience as the majority of students admit that they do not like writing for short bursts of time. Rather the clear majority prefer to spend extended periods (at least half a day) focusing solely on their writing. This appears to suggest that finding time to write is a major challenge for this group of distance learners.

The students appear to be confident about their writing abilities, but also admit that the process of writing is a challenge. However, a number of those replying to the questionnaire who are close to finishing their courses do state that they feel that they have learned a great deal about academic writing and generally feel more confident than they did at the beginning of the programme.

The main challenges which writing presents appear to be related to features of distance learning itself. Some commented on the lack of physical resources due to their remote location, for example not being able to easily obtain paper resources such as books which exist in the university library, but which are not held in an electronic format. Two students commented on the lack of immediate tutor availability that can lead to anxiety, which relates to a comment from another student regarding feelings of isolation. The other reflection which came from three students relates to the support given online for assignment writing. Two exemplar assignments were made available but there was little deconstruction of the elements within those assignments or commentary to help students understand the reasoning behind the grades the assignments had been given. This meant that whilst they might be able to deduce elements such as structure and general issues around composition, referencing etc, there was little guidance to help understand the relationship between attained grade and mark schemes or deeper reflections on the detail of the assignments.

Interview findings

The questionnaires led us to focus on several themes in the online interviews:

- time;

- resources;

- networking with others;

- the nature of criticality.

Students found that there were a number of tensions in completing academic work whilst in full-time teaching. Most outlined how they created a clear rhythm in their writing activity, which helped them work productively, often by using set periods of time. For example, Respondent 1 stated,

“As I am working full time I would allow myself a two- hour break after arriving home and then would work for a few hours every other day during the week, as the other evenings would be spent for paperwork for work. I would then typically set aside either two half days at the weekend or one full day, so that I could still meet up with friends.” (Respondent 1)

This appears to reflect the questionnaire returns which showed that students prefer to find longer periods of time to immerse themselves in writing as opposed to merely fitting it in at points when they find they have often small, spare periods of time. However, for some students the writing process is much more difficult as they highlight that they are not only challenged by the amount of professional work they have to complete alongside their studies, but also the pressures of family life, for example,

“It is not easy to manage, so what I do sometimes is wake up very early to read and write and sometime also stay very late to do same. I have to give my family time in the evening to engage with them and during the day time, I have to be at work full time which did not give me time to do anything about my study or assignment.” (Respondent 3).

One interesting aspect of the interview returns was that whilst the questionnaires had suggested that students tended to work alone on their assignment writing, the interviewees gave rich reflections on the networks, predominantly inform in nature, they had relied on when writing assignments. For example, Respondent 2 outlines a number of collaborative activities, from discussing potential topics, to sharing papers. Hence, networks of support were being developed away from the formal structures of the course.

“I worked with others somewhat during my writing process. Initially, this involves informal conversations with other students regarding our topics and using each other to informally explore ideas we were considering. There was also the occasional sharing of an article that was relevant to another student’s topic. This stage was very useful as it allowed me to get feedback regarding how interesting my topic was to other people in the field and course plus it allowed me to discuss the topic and have other people provide other avenues for me to explore.” (Respondent 2).

Resources from the course were also used to support writing. More than one interviewee highlighted the utility of the exemplar assignments which had been made available, for example, Respondent 4 stated,

“I think the examples of proper and successful writing were extremely helpful as they give you an idea of what should be done at this level of academic writing.” (Respondent 4)

Again, this is in contradiction to some of the open responses from the questionnaire, but there may be a level of self-selection bias in the replies from the interviewees. Indeed, there is clear evidence that whilst the exemplars were seen as a useful resource, further contextualization and explanation of them in support of writing would be very useful.

Some respondents also discussed how they had integrated the weekly work activities from their studies into their writing process, showing that they were making direct use of the information and resources to inform their assignment writing.

“I relied on the weekly material a lot, in order to inform an understanding of the module which would lead to the choice of topic. I also used the resources listed on the module, both to write my assignments and as a starting point to research more articles by the same authors or on the same subject.” (Respondent 5).

Two respondents also highlighted the importance of contact with tutors as a resource, and in one case (Respondent 1) suggested a way of using this resource more productively to help students in their writing,

“It would be very helpful to perhaps have a time slot (I know this is challenging on a distance learning course due to time zones) whereas students we could have a form of question time with some of the tutors from the course.” (Respondent 1).

Finally, we included a question relating to criticality as we reflected that this is a major focus of writing at masters level, but that there is often an assumption that students understand what it means and how to integrate it into writing without ever understanding if this is actually the case or not. Two respondents left the question unanswered which may indicate a lack of confidence, whilst Respondent 3 gave a useful, simple definition.

“I would define Criticality as an in-depth understanding of a particular work concept, which leads to questions as to why the writer is developing his/her writing in such a way, and facts that surround it.” (Respondent 3).

This suggests, alongside previous research we have conducted (Edirisingha & Wood, 2018), that greater support is required for helping distance learners explore the meaning and application of criticality in their writing, a focus which we think may often be ignored in programme materials.

Initial Reflections

Little is known about how distance learners approach their written work, especially in terms of use of resources, the temporal aspects of how written work can be intertwined with professional and personal responsibilities, and how they can best be supported to enable them to reach their academic potential. The initial insights gained from this small-scale study suggest a complex picture of highly differentiated ways in which individuals choose to work. They manage their time in different ways to fit with the idiosyncratic pressures they experience. There is also a spectrum of resource and support use, with some students preferring to work in a very individualistic manner, whilst others begin to form informal support networks. Some students make extensive use of the course resources as a foundation for their work whilst others do not. It is also the case that further support resources are required to help students to fully understand what is expected of them and how to develop their academic writing.

The main elements of the process which show a level of similarity across the cohort are the development of positive working relationships with tutors who are seen as crucial in supporting the writing process, and the ubiquitous use of technologies. However, on this latter point, there is a tendency to assume students know how to make use of technologies to greatest effect, but do we need to consider how to support better, and more critical use of technologies to support writing processes?

References

- de Chazal, E. (2014). English for Academic Purposes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Edirisingha, P., & Wood, P. (2018). From Evaluation to Sensemaking: Emergent Development of a Masters Distance Learning Research Methods Module. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, Special Issue: Best of EDEN 2016. Retrieved from http://www.eurodl.org/materials/special/2018/Oldenburg_041_Edirisingha_Wood.pdf

- Huerta, M., Goodson, P., Beigi, M., & Chlup, D. (2017). Graduate students as academic writers: writing anxiety, self-efficacy and emotional intelligence. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(4), 716-729.

- James, N., & Busher, H. (2009). Online Interviewing. London: Sage.

- Wood, P., & Cajkler, W. (2016). A participatory approach to Lesson Study in higher education. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, 5(1), 4-18.

Appendix 1

Questionnaire

Appendix 2.

Interview text and questions

Dear student

Thank you for including your e-mail in the recent questionnaire focusing on experiences of writing as a distance learner. If you are still happy to answer some interview questions that would be great, the instructions are below. If, however, you have now decided not to take any further part in our research, please feel free to stop reading now.

We have included a participant information sheet and an informed consent form (attached) and would ask you to have a look through and sign the consent form if you choose to carry on (an electronic signature is fine).

Below are seven interview questions. You are free to answer these questions either as written responses in a return e-mail, or as a voice recording if you have the kit to record a voice file. Whichever is easier for you. Once you have either typed or recorded responses, please send them to us. The data will obviously be treated confidentially, and any reporting will be either aggregated or anonymised. Once we have analysed your responses, we may want to send through a couple more questions for clarification, but again your decision concerning involvement can be revisited again at that point.

Interview questions.

- Over the period during which you developed your assignment, please describe your general pattern of work (e.g. did you read and then write, did you read and write in cycles, etc.).

- How did you work with others, if at all, during the writing process? If you did, what do you think are the advantages of sharing ideas and work?

- Please describe the nature and impact of any networks of support you engaged with during the writing process?

- How might the exemplars offered to you be developed as a helpful resource for writing?

- How did you try to manage the time tensions between full-time work and academic study/writing?

- If you used the materials from the weekly work packages to inform and help with your assignment writing, how did you do this?

- How would you define the concept of ‘criticality’

and how has the writing of your first assignment helped you develop this part

of your work, if at all?