Moody MOOCs: An Exploration of Emotion in an LMOOC

Elaine Beirne [elaine.beirne@dcu.ie], Conchúr MacLochlainn [conchur.maclochlainn@dcu.ie], Mairéad Nic Giolla Mhichíl [mairead.nicgiollamhichil@dcu.ie], Dublin City University, Ireland

Best Research Paper Award Winner

Abstract

This paper reports on the emotions experienced by participants of a language learning MOOC or LMOOC. It has been previously shown that emotions play a key role in the learning process. Therefore, identifying and understanding the emotions experienced in new learning environments, such as LMOOCs, is of particular importance. This study was conducted during the first iteration of the Irish language and culture MOOC, Irish 101, which is delivered through the FutureLearn platform. An analysis of both self-report data and in-course learner comments is conducted to identify the emotions experienced during various content steps in the LMOOC. We found that positive emotions, such as curiosity, excitement and pride, were reported most strongly by participants throughout the course. However, certain sections of content evoked comparatively stronger instances of negative emotion such as frustration and confusion. Examples of how these emotions manifested in the discussion posts are also presented. This paper concludes by discussing the potential of emotion research for informing LMOOC design.

Abstract in Irish

Tuairiscítear sa pháipéar seo na mothúcháin a bhraith daoine a bhí rannpháirteach i MOOC foghlama teanga nó LMOOC. Tá sé léirithe go bhfuil baint mhór ag mothúcháin leis an bpróiseas foghlama. Tá tábhacht mhór dá bhrí sin leis na mothúcháin a bhraitear i dtimpeallachtaí nua foghlama, mar LMOOCanna, a aithint agus a thuiscint. Le linn na chéad chuid den MOOC Gaeilge agus Cultúir, Gaeilge 101, a cuireadh ar fáil ar an ardán Future Learn a tugadh faoin staidéar seo. Tugtar faoi anailís ar shonraí a thuairiscíonn na rannpháirtithe féin agus tuairimíocht an fhoghlaimeora le linn an chúrsa d’fhonn na mothúcháin a bhraitear le linn na gcéimeanna éagsúla ábhair i LMOOC a aithint. Fuaireamar amach gur mothúcháin dhearfacha, mar fiosracht, ríméad agus bród na mothúcháin ba mhó a thuairisc rannpháirtithe le linn an chúrsa. Spreag míreanna áirithe ábhair mothúcháin láidre dhiúltacha inchomparáide, áfach, mar frustrachas agus mearbhall. Tá samplaí tugtha freisin de na bealaí ar cuireadh na mothúcháin seo in iúl sna postálacha plé. Ag deireadh an pháipéir seo déantar plé ar an bpoitéinseal a bhainfeadh le taighde ar mhothúcháin chun leagan amach LMOOC a chur ar an eolas.

Keywords: learner emotions, online language learning, MOOC, learning design, mixed method

Introduction

For a long time, emotions were considered to be outside the realm of rational thought and thus systematically ignored in educational research. In the past few decades, however, educational science has been experiencing an affective turn (Pekrun & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014). Increasing interest in emotions in education has emerged in the literature following recognition of the inextricable link between cognition and emotion. Subsequent research has proven that emotions have a significant impact on learning achievement (Pekrun, Goetz, Titz, & Perry, 2002). Despite this progress, there remain many learning contexts where the relationship between emotions and learning is less understood.

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are online instructional platforms that have grown in popularity in the past decade, in particular among higher education institutions. In 2017, over 800 Universities around the world had launched at least one MOOC (Shah, 2018). The high expectation associated with the influx of MOOCs into higher education has provoked a burst of research focused on improving pedagogical and technical approaches in order to maximise their effectiveness. While the majority of this research has been student-focused (Veletsianos & Shepherdson, 2016), the affective dimensions of learning have not received as much attention in MOOC research. The role of emotion in online learning contexts such as MOOCs is of particular importance considering the regulatory role of instructors in face-to-face environments and the corresponding lack of such support for online learners. The role of a teacher involves understanding and responding to student emotional patterns (Mayer, 2004), providing assistance and reacting to prompts. In comparison, online instruction, even when synchronous, relies on a delayed form of reaction. A far greater reliance is placed on adequate design, appropriate pedagogical foundations and ensuring frequent contact with instructors.

Initial investigations of emotion in a MOOC context have used MOOC discussion forums (Wen, Yang, & Rosé, 2014) and click stream data (Leony, Muñoz-Merino, Ruipérez-Valiente, Pardo, & Kloos, 2015) to infer student emotion. Dillon et al. (2016) however, utilised a self-report approach, giving voice to the student and the subjective nature of emotion. They investigated student emotion during an introduction to statistics MOOC, obtaining self-report data at multiple points during the course. The current paper reflects this approach, addressing key questions about student emotion in a language learning MOOC (LMOOC). Learning a language is not comparable to learning other subjects. This is mainly because of the social nature of such a venture. The process is not only knowledge-based but mainly skill-based, requiring interaction with other speakers and the use of higher order thinking skills, not just memorisation and mechanical reproduction (Bárcena & Martin-Monje, 2015). As a result, facilitating the acquisition of language-specific skills is a significant challenge in an online context, in particular in a MOOC context which consists of potentially thousands of heterogeneous students and templates that promote a transmission-based approach to learning. However, as Sokolik (2014) points out, the infancy of LMOOCs presents us with an opportunity to ‘get it right’, informed by the mistakes of the past. A greater understanding of learner emotions in an LMOOC context could enhance this process.

The Current Study

This study explores the presence of emotion in the Irish language MOOC, Irish 101, provided by Dublin City University in Ireland, through an analysis of self-report data and discussion forum posts.

The following two research questions will be addressed:

- What emotions do learners self-report when engaged in an LMOOC?

- Is there evidence of these emotions in course discussion posts?

Method

Learning Environment

We conducted this study during the first iteration of an Irish language and culture MOOC, Irish 101, which is hosted by the FutureLearn platform. This MOOC is offered by DCU as part of the Fáilte ar Líne (Welcome Online) initiative. This project is co-funded by the Irish Government, specifically the Department of Culture, Heritage, and the Gaeltacht, under the Twenty-Year strategy for the Irish Language, with support from the National Lottery. The course was designed for ab-initio learners of the Irish language. It began in January 2018 for three weeks, consisting of approximately 4 hours of learning per week. The content each week is broken down into 32 steps on average and these steps are grouped under various themes such as greetings, hobbies, giving directions etc.

Procedure

An experience sampling approach was used to collect self-reported data pertaining to learners emotions during the course. Following various steps, learners were prompted to self-report on the emotions they experienced while learning during that step. The survey appeared as a link within the step. It was intended that the immediacy of the measurement would reduce the retrospective bias inherent in self-report data. There were 6 data collection points per week (18 in total). All responses were anonymous and participation was optional.

An analysis of discussion forum posts for two exemplar steps was then conducted to identify if, and how, the emotions identified by the survey were expressed by participants during these steps. This qualitative analysis of learner comments was intended to supplement the survey results and provide important contextual information that addressed some of the limitations of the quantitative instrument, in particular, the lack of subjective articulation of emotions. It also opened up an avenue to explore the reasons why learners expressed these emotions. This multiple methods approach was ensured that the research was “…inclusive, pluralistic and complementary” (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2014; p.17). Ethical approval for the study was obtained from DCU’s Research Ethics Committee in January 2018 (DCUREC/2017/205).

Emotion Measures

Survey Instrument

The short version of the Epistemic Emotion Scale (EES) developed by Pekrun, Vogl, Muis, and Sinatra (2017) was used to assess students’ learning-related emotions due to the fact that it is minimally invasive and thus suitable to an experience sampling approach. This version of the scale contains one item per emotion, measuring a total of 7 emotions: surprise, curiosity, enjoyment, confusion, anxiety, frustration and boredom. Adaptations to the scale to account for an Irish language learning context included the addition of a further four emotions: hope, hopelessness, pride and anger. These, and the other emotions on the scale, were found to be relevant to Irish language learning during prior research conducted by the study’s team. The final scale investigated eleven emotions. Participants responded to each item using a 5-point Likert scale in which they were asked to indicate how strongly they felt the emotion from 1 = not at all to 5 = very strongly. Contextualised instructions were included to address each task type.

Discussion Posts

At the end of each step in the course, learners had the option to contribute to a discussion forum. One exception to this was during quiz steps. Comments posted in the discussion forum for two exemplar steps investigated by the survey were downloaded and coded as positive, negative or neutral. They were then further categorised into subject themes which allowed researchers to identify contrasting and supporting evidence for the survey results.

Findings

Survey Results

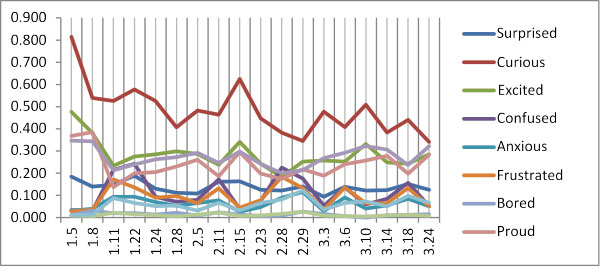

Of the 10,464 people who enrolled for the course, 2931 learners completed the survey at least once during the course. The emotion felt most strongly by participants during the course was Curiosity, with over 55% of respondents reporting Strong or Very Strong instances of curiosity. This is followed by Excitement (32%), Hope (28%) and Pride (26%). Figure 1 presents a breakdown of the reported emotion over the 18 data collection points. Notably, emotions varied with regard to different sections of content during the course. Curiosity, while remaining the emotion reported most strongly by participants throughout, experienced a gradual decline over the course. Step 2.15 (cultural article about place names) proved to be an exception to this as curiosity increased significantly during this step. Following a sharp decline at the beginning of the course, other positive emotions such as excitement, pride and hope remained relatively stable throughout the course. Mirroring curiosity, these positive emotions were also experienced strongly by participants during step 2.15. Step 3.10 (Vocabulary for giving directions) also evoked positive emotions among respondents. The strong presence of positive emotion is comparable to the results of the Dillon et al. (2016) study. They found that the positive emotions of Hope and Enjoyment were the most frequently reported among the participants of their statistics MOOC.

Figure 1. Distribution of emotion over course

While positive emotion dominated throughout, some content evoked comparatively stronger reports of negative emotion. For instance, the percentage of participants identifying strongly with confusion increases 7-fold, from 3% to 21%, during step 1.11 (Conversation Video) compared to step 1.8 (Quiz) of the course. Again during step 2.28 (Grammar Quiz) strong reports of confusion increased significantly when compared to the previous steps investigated. Interestingly, other negative emotions such as anxiety, frustration and hopelessness follow the same pattern to varying degrees during these steps. These spikes in negative emotion also correspond with drops in the reports of strong positive emotions during the same steps.

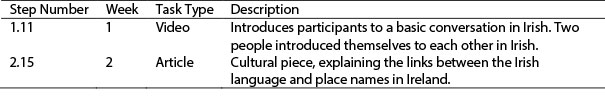

These survey results highlight that learners experience certain emotions more strongly during different sections of content in an LMOOC. In order to explore these results further, two steps were selected for specific comment analysis due to their distinctiveness among the survey results. Step 1.11 was chosen for its comparatively high negative emotional reaction, particularly following mainly strong positive emotion reports prior to that step. Step 2.15 was selected for its particularly strong positive emotional trend. For a description of these steps see Table 1.

Table 1: Description of steps

Discussion Post Interpretation

1.11 Conversation Video

The survey results indicated that this step provoked comparatively strong reports of negative emotion. Despite this, curiosity and excitement were still the emotions reported mostly strongly by respondents. The analysis of learner comments during this step, however, identified predominantly negative posts from learners. Many expressed concern that the video content was too difficult, referring to pronunciation and the speed of the conversation. Reference was also made to non-linguistic aspects of the video such as the long introduction and background music. Interestingly, this was one of the first interactions learners had with a linguistic task which in this case was listening. Previous steps consisted of introductory blocks of grammar and culture.

“Found this video a little too fast, also would like know what they are saying.” (Learner A)

“A lot of intro and music to a very fast conversation. Not very helpful to a novice.” (Learner B)

“Perhaps the jump from single words to quickly spoken sentences is a little sudden? Slowing down the interaction just made them sound very strange.” (Learner C)

The comments also indicated that some learners returned to the step having completed successive steps in which the linguistic elements of the video were explained in more detail. This highlights the importance of how activities are structured for learner understanding.

“Just realizing all these phrases are explained in future lessons…” (Learner D)

Finally, it is also important to note the role of learner interaction during the course, with many participants encouraging each other, suggesting that learners potentially play a role in regulating emotions.

“Good job! I can’t do that yet” (Learner E)

2.15 Cultural Article

In contrast to the difficulties found in step 1.11, step 2.15, in which learners explored Irish language place names, showed strong increases in positive emotions, such as curiosity, excitement and pride. Learner comments pointed to several possible reasons for this, such as intrinsic enjoyment of the task:

“The Irish place names are quite fascinating as they have history and location built into them” (Learner F)

Contextual application of the knowledge in the step to existing learner knowledge (the step prompted learners to talk about their own home-places and their lexicological origins):

“A very interesting section. Caloundra where I live in Australia is on the coast. The word Caloundra is an Aboriginal word meaning 'place of the beech tree' or 'Callanda' a beautiful place, which it is.” (Learner G)

A general enjoyment of the discussion relating to place names:

“A fascinating section. Love all the comments” (Learner H)

A mixture of both pride and aesthetic appreciation of the language:

“It strikes me how lyrical and visual the original place names are” (Learner I)

This strong positive reaction speaks to the potential usage of cultural teaching embedded within grammatical tasks as a way of provoking strongly positive responses and engagement from learners.

Conclusion

Identifying the emotions experienced within LMOOC environments is an important task. Our results show that learners experience a variety of both positive and negative emotions while learning with different types of content in an LMOOC. We also found that broadly positive and broadly negative emotions appear to move in tandem. At a macro-level, the results show that Curiosity is the emotion participants felt most strongly; however, it is within the variation of the less commonly reported emotions that the, arguably, more valuable findings emerge.

There are a few limitations in this study. Firstly, we acknowledge that our results may be biased by the high rate of attrition in the MOOC. This was reflected in survey responses and course activity. Secondly, due to the anonymity of the surveys it was not possible to determine whether the survey sample reflected the participants who contributed to the discussion forums in the course, although some overlap is likely.

Our analysis points to several implications for LMOOC and also MOOC design more generally. Significant diversity was found in learner emotions, pointing to the need for designers and instructors to understand these distinctions and their potential role in learning at a distance. Furthermore, the analysis of discussion forum posts proved useful in identifying the reasons why learners experienced certain emotions. This highlights some of the benefits of qualitative research in a field that to date has been dominated by quantitative studies. Further research with regard to emotion antecedents would be beneficial in informing teaching strategies and interventions that encourage positive emotions during learning in a MOOC environment.

References

- Bárcena, E., & Martin-Monje, E. (2015). Introduction: Language MOOCs: An emerging field. In Language MOOCs: Providing Learning, Transcending Boundaries (pp. 1–15). https://doi.org/10.2478/9783110422504.1

- Dillon, J., Bosch, N., Chetlur, M., Wanigasekara, N., Ambrose, G. A., Sengupta, B., & D’Mello, S. K. (2016). Student Emotion, Co-occurrence, and Dropout in a MOOC Context. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Educational Data Mining. Raleigh, North Carolina, USA: International Educational Data Mining Society (IEDMS).

- Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. (2004). Mixed-methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14-26.

- Leony, D., Muñoz-Merino, P. J., Ruipérez-Valiente, J. A., Pardo, A., & Kloos, C. D. (2015). Detection and Evaluation of Emotions in Massive Open Online Courses. Journal of Universal Computer Science, 21(5), 638–655.

- Mayer, J. D. (2004). What is Emotional Intelligence? UNH Personality Lab, 8.

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic Emotions in Students’ Self-Regulated Learning and Achievement: A Program of Qualitative and Quantitative Research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4

- Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2014). International Handbook of Emotions in Education. Routledge.

- Pekrun, R., Vogl, E., Muis, K. R., & Sinatra, G. M. (2017). Measuring emotions during epistemic activities: the Epistemically-Related Emotion Scales. Cognition and Emotion, 31(6), 1268–1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1204989

- Shah, D. (2018, January 18). By the numbers: MOOCs in 2017 [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.class-central.com/report/mooc-stats-2017/

- Veletsianos, G., & Shepherdson, P. (2016). A Systematic Analysis and Synthesis of the Empirical MOOC Literature Published in 2013–2015. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(2). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/2448

- Wen, M., Yang, D., & Rosé, C. (2014). Sentiment Analysis in MOOC Discussion Forums: What does it tell us? In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Educational Data Mining. London, United Kingdom: International Educational Data Mining Society.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted as part of the Fáilte ar Líne – Welcome Online project, which is co-funded by Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht under the Twenty-Year Strategy for the Irish language with support from the Irish National Lottery.