YouTube as a Repository: The Creative Practice of Students as Producers of Open Educational Resources

Helen Keegan [h.keegan@salford.ac.uk]

Computing, Science and Engineering, University of Salford

Frances Bell [f.bell@salford.ac.uk]

Salford Business School, University of Salford M5 4WT

University of Salford, MediaCityUK, Salford Quays, Greater Manchester, UK, M50

2HE

[http://www.salford.ac.uk]

Abstract

In this paper we present an alternative view of Open Educational Resources (OERs). Rather than focusing on open media resources produced by expert practitioners for use by peers and learners, we examine the practice of learners as active agents, producing open media resources using the devices in their pockets: their mobile phones. In this study, students are the producers and operate simultaneously as legitimate members of the YouTube community and producers of educational content for future cohorts. Taking an Action Research approach we investigated how student’s engagement with open media resources related to their creativity. Using Kleiman’s framework of fives conceptual themes which emerged from academics experiences of creativity (constraint, process, product, transformation, fulfillment), we found that these themes revealed the opportunities designed into the assessed task and provided a useful lens with which to view students’ authentic creative experiences.

Students’ experience of creativity mapped on to Kleiman’s framework, and was affected by assessment. Dimensions of openness changed across platforms, although the impact of authenticity and publication on creativity was evident, and the production of open media resources that have a dual function as OERs has clear benefits in terms of knowledge sharing and community participation.The transformational impacts for students were evident in the short term but would merit a longitudinal study. A series of conclusions are drawn to inform future practice and research.

“The most important thing in our rapidly changing society is not to amass some certain knowledge forever, but to be able to throw out obsolete knowledge, to be ready to start over, to see the world with fresh eyes” (Kupferberg, 2003)

Keywords: OERs, Creativity, Mobile, YouTube, Producers, Community

Topics of the paper

- Introduction

- Creativity

- Open educational resources

- Why mobile phone films?

- Researching two years of mobile film projects

- The mobile video case

- Results

- Discussion

- Creativity and OERs

- Conclusions

Introduction

UK Higher Education (HE) in the 21st Century is changing. Government funding of HE has gradually shifted from the government funding provision directly to funding via a graduate contribution system, putting students as customers whose demand drives the number of places in different universities and how teaching is delivered (Browne, 2010; Hall, 2010). As students invest more in their education and look forward to a long period of debt, employability looms large with the vocational and practice-based elements of degrees assuming increased significance for students. This shift is beginning to be recognized by HE institutions and by academics as they design and deliver curricula.

There is a long tradition of education being linked to practice: Dewey saw experiences as both the means and the goal of education (Dewey, 1998), first published in 1938. Practical outcomes need not be mundane, indeed creativity is valued by employers. However creativity is scarce as an explicit learning outcome in the UK academic curriculum, and companies that employ graduates invest in training for them to learn creative ways of thinking (Norman Jackson, 2002).

Converging technologies and web services offer new opportunities for mediating personal, social and organisational practices. ‘Everyday’ devices and services such as smartphones1[1] and social networking and knowledge sharing services like Facebook, Twitter, blogs and wikis have become part of the tapestry of our daily lives - personal, study and work (COMSCORE, 2010). These devices can be used to capture, remix and share media, which has led to a rise in participatory culture, an acceptance of imperfection and the authentic experience of creativity as a social process (Gauntlett, 2011). Whether or not we can define exactly what staff and students will do in converging technology contexts where personal devices are used for both ‘work’ and ‘play’, we can assert that engagement in authentic and reflective practice offers opportunities for creativity and relevant learning.

The context for our study is the Professional Sound and Video Technology (PSVT) degree, a vocational undergraduate degree that prepares students for employment in the broadcast industries - industries that are themselves in a state of flux due to technology and media convergence. Possibilities for learning, teaching, creating and publishing across multiple open platforms and mobile devices mean that it is increasingly important for students on vocational programmes to not only ‘know the subject’ but also to prepare themselves for dynamic industries where the only thing that is certain is change. The final year Advanced Multimedia module combines vocational relevance with a critical approach whereby students are encouraged to reflect on their professional practice and develop an understanding of past, present and future developments in their chosen industry. The reflective nature and creative ethos of the module sets it apart from others on the programme, with its focus on open media production and communication rather than technology per se. As well as defining a range of competencies through learning outcomes, the module places an increased emphasis on platform-agnosticism[2], individual interests and learner-centered assessment. For the past 2 cohorts, students have been assigned assessed group work of using their mobile phones to make short films that are published openly.

In an HE context where employability is a key driver, and the links between subject content and professional practice are valued, emerging technologies offer students opportunities to engage in authentic and up to date creative experiences. The outcomes of those experiences can be published media resources, in this case on YouTube, open to review by anyone. We have an incomplete understanding of the effectiveness of this type of learning activity influencing student practice. In this paper we aim to increase understanding by addressing the following question:

How does students’ engagement with open media resources relate to their experiences of creativity?

We examine the literature on Creativity, Open Educational Resources and Mobile Phone filming, followed by a description of our research methodology, the details of the case, and the results. In the next section, we analyse and discuss student experiences of creativity and their relation to Open Educational Resources. Finally we draw conclusions to inform future practice and research.

Creativity

The nature and definition of creativity has been the subject of debate for hundreds of years, yet it is only in recent times that creativity has been conceptualised as a life-skill; no longer the preserve of the arts or exceptional individuals, creativity has entered the discourse as a societal as well as personal competence which is essential for a learning society in the modern age (Loveless, 2002). However the idea of ‘core competences’ is not uncontroversial; for example Kupferberg sees the notion as reductive and a relic of an industrial mindset. Competencies - despite their necessity - may even act as barriers to original thinking as due to their rigidity (Kupferberg, 2003; Leonard-Barton, 1995).

In education, creativity is no longer tied to particular disciplines or epistemologies, but is now a feature of recent curriculum frameworks alongside employability, enterprise and innovation (Kleiman, 2008). Whilst it still conceptualised differently across disciplines, creativity is generally defined as the development and production of something ‘novel’, of ‘value’, with distinctions drawn between the product and the process (and also person and place). Further theoretical frameworks have been used to view creativity through multiple lenses, for example as a social practice (Amabile, 1996; Knight, 2002), as a digital literacy (Walsh, 2007), in terms of its relation to new technologies (Sefton-Green, 1999), or as a combination of these conceptualisations (Gauntlett, 2011).

Aspiring to creativity as an outcome of education does not guarantee its delivery, as education can stifle rather than promote creativity (Knudsen, 2010; Robinson, 2007). At the same time, while the constraints imposed by educational processes can be seen as prohibiting creativity, creativity can also be viewed as (or even triggered by) a reaction to constraint, working “across the boundaries of acceptability in specific contexts” and “exploring new territory and taking risks” (N. Jackson & Shaw, 2005)

Kleiman’s (2008) conceptual map of creativity in learning and teaching frames our analysis of student practice in mobile video. Constraint, process, product, transformation and fulfillment are the categories of experiences of creativity derived inductively from interviews with 12 UK academics across a range of disciplines. Constraint provided a focus for creativity when academics saw constraints as possibilities for enabling student creativity, when ‘systems’ imposed barriers to creativity, and when constraints formed a trigger to the academics’ own experience of creativity in producing ‘workarounds’. Process-focused creativity can be seen as leading to an explicit outcome (possibly a creative product); leading to an implicit outcome (say, having a creative experience); or with no outcome where the creative experience could be of playing for its own sake. Where the focus is on the Product, the emphasis could be on newness and originality or on the production of utility and value. Of course in the re-mix culture, originality is re-interpreted, particularly in media-sharing communities such as YouTube, where re-mixing of media is seen as participative and creative. Kleiman sees Transformation-focused experiences of creativity as “an engagement in a process that is transformative, either in itself, or is undertaken with the intention (implicit or explicit) of being transformative”. Creative experiences with a focus on Fulfilment are characterised by personal commitment and a sense of achievement.

These conceptions of creativity include disorientation and encountering the unexpected - unconventional approaches to learning and teaching in contrast to the more conventional pedagogical devices of scaffolding and frameworks. We build on Kleiman’s conceptual framework derived from academics’ perceptions of creativity by applying it to student perceptions of creativity in the context of a media creation project that challenges some of what they have been taught on other parts of their degree programme. Media constraints and disorientation are viewed as discontinuities in the learning process (Lanzara, 2010) that have the potential to transform learners through facilitating deep learning and reflection.

Open educational resources

In this paper we explore creativity as something that can be experienced by groups of students when they are asked to create a (public) media artifact using a tool that is a personal device rather than one that would form part of their normal learning resources. Although resources may include print and even people (Downes, 2007), Open Educational Resources are generally seen as digitised materials offered freely and openly for educators, students and self-learners to use and reuse for teaching, learning and research (Hylén, 2007). However, these resources exist within communities that produce, use and sustain them (Downes, 2007) and form part of participatory pedagogies (Brown & Adler, 2008) that characterise the student as active and engaged. Demand-pull learning emphasises student authentic participation in communities that go beyond their classroom.

“passion-based learning, motivated by the student either wanting to become a member of a particular community of practice or by just wanting to learn about, make, or perform something” (Brown & Adler, 2008).

However, in much of the discussion on OER, the emphasis is on teachers’ creation and finding of knowledge for students to use. Postgraduate student work is increasingly ‘owned’ by institutions (Stacey, 2007) and although joint content development by teachers and students is predicted (IIEP, 2005) cited in (Stacey, 2007), students are primarily seen as consumers rather than producers of OERs.

Hoyle’ distinguishes between big and little OERs (Hoyle, 2009) where big OERs are institutional repositories of teaching materials with explicit aims and quality control procedures and little OERs are produced by individuals, have low production values and shared through third party services (Weller, 2010).[3]

Why mobile phone films?

In this study, we are introducing mobile phones as creative tools whose use is free from the normative constraints of established practices using high-end equipment. Mobile phone film-making lends itself well to a creative pedagogy based on user-generated content (UGC) and open media production/consumption, as short-form video is easy to produce on a mobile phone and is ideally suited to viewing and sharing between mobile devices and across the web. Through the rising genre of mobile filmmaking a new aesthetic has emerged, emphasizing the importance of location and the everyday (Baker, Schleser, & Molga, 2009). ‘Mistakes’ such as pixellation and shakiness are viewed as characteristics of the medium. The projects set for students are in the spirit of the ‘good enough’ movement that combines a new aesthetic with the experience of creating digital media, where the importance of the content (subject matter) and its context of use overrules low production values (Engholm, 2010). This pragmatic approach is consistent with the Deweyian tradition of experiential learning that pervades vocational degree programmes. Mobile phone films offer an authenticity in content which can lead to a heightened sense of verisimilitude; as short-form films gain importance as a type of web-based media, so it becomes clear that the understanding of, and ability to produce such content is desirable for these students.

Students engage actively with a range of digital technologies through the production of open media resources. They are encouraged think about user-generated content in a different way and develop an appreciation for the potential for mobile devices as creative tools. The intention is for them to develop an appreciation for participatory media production and to think ‘outside the box’, developing skills in the production of (UGC) and thinking editorially, as opposed to the more traditional narrative-based approach to film-making. Through engaging with a range of open media resources as both consumers and producers, and producing mobile films which necessitate the development of innovative approaches to overcome constraints of the medium crossing the boundaries between traditional and new paradigms, we offer the learners greater opportunities for creativity in their practice.

Researching Two Years of Mobile Film Projects

Action Research (AR) is an approach that allowed us to solve practical problems in a higher education module, and to test and generate theory (Baskerville, 1999; Mumford, 2001). AR is essentially cyclical in nature, e.g. Checkland’s Framework for AR (Checkland & Holwell, 1998) and Susman and Evered’s 5 stage AR Process (Susman & Evered, 1978). Our approach was consistent with the ‘new Action Research’ where the emphasis is more on individual flourishing within a community and less on contribution to scientific knowledge (Oates, 2004; Reason & Bradbury, 2001). The first author designed the learning activity, collected data and conducted ongoing reflection throughout the process, with the second author acting as ‘critical friend’ (Kember et al., 1997). Both authors reviewed the literature before, during and after the student projects, writing and reflecting via a shared private space. Students were also participants in the research, contributing valuable process data and reflections via their blogs and wikis; and making their own practical achievements. The AR project ran from November 2009 to December 2010, involving 2 cohorts of students (n=25 in 2009, n=23 in 2010). Two separate mobile film/OER projects took place, each lasting for 6 weeks (Nov-Dec 2009, Nov-Dec 2010). The personal reflections of the tutor during and after the 2009 project informed the design of the 2010 project: in 2009 an appreciation of the scope for creativity emerged as the overriding theme in student evaluation and feedback, closely followed by their acknowledgment of the benefits of publishing work openly. However, further study was required to identify why and how students were experiencing creativity and how this related to the publication of open media resources (if at all). A more targeted approach was taken to data collection in 2010. Research data was collected from a range of sources, both online and offline:

- Mobile films and comments on them (open resources hosted on YouTube)

- Reflective blog posts (open resources hosted on Wordpress)

- Group wikis (open resources hosted on Wikispaces/PBWiki)

- Photo-diaries (open resources hosted on Flickr)

- Module evaluation questionnaires

- Participant observation + session notes

The information generated from the dataset, while mainly qualitative in nature, was coded into emergent themes through intertextual analysis of the films alongside the other open resources that were produced. Critical incidents were recorded, alongside ‘vignettes’ which highlighted key (both expected and unexpected) issues. Open blogs and wikis have not been quoted verbatim (in accordance with University ethical approval) as a web search could reveal the identity of the author.

The Mobile Video Case

The BSc (Hons) in Professional Sound and Video Technology at the University of Salford is a course in production skills for the broadcast industry. Students, who are typically in their early 20s, aim to work full time as engineers, production professionals or technicians. All entrants to the BSc conversion year have successfully completed a two-year HND course that is practice-based with a heavy emphasis on technical skills. Two-thirds of these students come from other institutions, and many have no prior experience of video production; the remaining students have studied at Salford and already have some skills in the production of video using high-end equipment. For all students, making short films using mobile phones is novel, and counter-cultural to the technology focus of their previous practice. They are working away from their ‘comfort zone’ as they are not able to rely on high-end equipment.

The module under study (Advanced Multimedia) encourages students to engage critically with mobile and web-based technologies, developing their online presence and digital identity alongside experimentation with open participatory media production with a view to identifying how these technologies can be used professionally. The emphasis is on using digital media effectively across a range of open platforms, encouraging the learners to work openly and creatively and to consider issues and techniques in relation to multi-channel content production.

In this project, PSVT students worked in groups to produce short practice-based films shot entirely on their mobile phones, developing imaginative and innovative filming techniques through exploring the affordances of the technology. Each cohort was introduced to mobile film-making through a masterclass delivered by Hugh Garry from BBC Audio and Music, winner of a Media Guardian Innovation Award in 2009 for “Shoot the Summer”, a film shot entirely on mobile phones. The aim of the masterclass was to inspire the group to consider techniques and approaches that challenged students’ received wisdom and exploited the affordances of the medium. They were free to make their films on any subject of their choice, and were asked to collaborate on the development of ideas and negotiate their chosen subject/genre within their group – openness was a theme of the module. With an emphasis on open content and open platforms, groups were responsible for managing their own projects through wikis, which were authored collaboratively and used to document the overall research and production processes and present the final project report. A visual diary of the ‘making of’ each film was presented in Flickr, alongside textual commentary (using overlay notes and descriptions) that linked to the corresponding wiki, offering the viewer a rich insight into their creative and technical processes. Each student was also asked to write 3 reflective blog posts at key stages of the project: beginning, middle and end. By producing open content across multiple spaces, both as a group (film, wiki, Flickr) and individually (reflective blogs), the students were able to publish their final creative product (the film) and describe and reflect on the creative processes which led up to that product. The films were presented to students and staff in a mini ‘film festival’. All materials were made openly available online – a total of 13 films were produced: 7 in 2009, 6 in 2010.

Results

Table 1 Mobile Films produced in 2009/10 (hyperlinked to available films)

2009 |

2010 |

|

No. of students |

25 (2 female/23 male) |

23 (3 female/20 male) |

% who own camphones |

60% |

90% |

No. of films produced |

7 |

6 |

Films (titles with links to those we have permission to publish in this paper) |

The Move From Busk ‘til Dawn Live at Newton A Mobile Intrusion Mobile Productions |

Killing in Your Eyes |

Camphone ownership increased significantly from 2009 to 2010, although the low ratio of female:male students remained fairly constant. Each group produced and published a final film, a collaborative wiki and Flickr photo diary, and individual reflective blogs. Films were between 3 and 5 minutes in length and demonstrated a range of influences, although owing to the collaborative nature of the project the audio-visual montage was the key feature of many of the films, particularly in 2010 when most students were able to film on their own devices.

Discussion

Through using multiple media across a range of open platforms the students were able to immerse themselves in the technologies as mobile networked learners and open content producers. Following the five conceptual themes that emerged in Kleiman’s study (constraint, process, product, transformation and fulfillment), we explore the students’ experiences of creativity in using and creating open media resources.

Constraint

The technical constraints of the mobile phones were generally experienced as opportunities to produce ‘workarounds’ and experiment with filming practice away from the orthodoxy. Many students (n=24) appreciated the way that the device limitations influenced their thinking about how to create the footage, and also added grittiness and realism. This is consonant with much of YouTube footage, immediate rather than slick.

However students did not always fully-embrace the more accidental aspects of the medium. One group had mistakenly filmed in different aspect ratios and orientations, but rather than treat this as a characteristic of the genre the group saw it as a failure and re-filmed in order to ensure consistency across scenes. A student from this group saw the solution in standardising video formats, a view that demonstrates how conventional film-making practice was still guiding the perceptions of some students, and their aversion to breaking the rules in spite of being encouraged to do so. There was a marked reluctance to move away from the constraints of conventional practice that could be related to lack of ego (Runco, 2008) or lack of confidence in risk-taking (Kleiman, 2008). This reluctance was not dispelled by the film “Shoot the Summer” (shown to them at the beginning of the project) that contained footage that ran counter-cultural to convention such as the camera falling over during filming. Despite our discussion of this being a relic of the medium, some students still did not feel comfortable or confident in using this kind of accidental footage. However, others expressed their appreciation for this new freedom from their prior experience of filmmaking techniques.

Process

The process-focused outcomes of the project were both explicit (the generation of a creative product, the films themselves) and implicit (having a creative experience within a group). Playing for its own sake was not an expectation of the project for either staff or students. Students clearly had fun but were not doing it for fun; although significantly, some of the students have gone on to make their own mobile films after taking part in the project.

One of the main aims of the mobile-film making exercise was for students to think about what they could do with a phone that they couldn’t do with a normal/high-end video camera, and they were specifically asked to develop imaginative and creative techniques. They demonstrated a range of innovative practices, often involving the placement of the phone e.g. inside a glass inside a fish bowl, stuck to a record as it spun around, placed inside a post-box. An interesting example of students developing their ideas in process was of one group where a student identified places where a phone camera would fit (down a grid, on a kite) and then used these ideas to develop the narrative with his group.

Although, in general, students were much more focused on making and editing the films than the process-related artifacts (images, blogs and wikis), one student did express the hope that their group’s wiki could be used in future as a reference, and another hoped that their film and their accounts of the development process could inspire others to make their own films.

Out of the 12 student films published on YouTube (originally 13, but 1 was taken offline after publication at the request of the subjects) only 2 groups were open about their project being part of their university coursework, explicitly mentioning the PSVT course - although 2 other groups did allude the film being part of a project. No group linked to their wiki/Flickr/blog posts from their film on YouTube, although linkages were made from the blog posts, wikis and Flickr to the film. Their films were presented as independent YouTube artifacts, suggesting that media published on other open platforms were seen as being peripheral to the film itself.

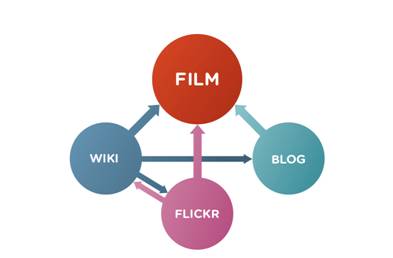

Figure 1 Links between platforms

Their attitudes towards, and levels of engagement with, the open platforms differed according to process and purpose:

- YouTube - the ‘cool’ space (tied to culture, high level of engagement)

- Wiki - the report space (tied to education, mixed level of engagement (high-medium))

- Blog - the personal space (tied to individual identity, high level of engagement)

- Flickr - the ‘strange’ space (“why do we have to use Flickr?”, low level of engagement)

Product

Due to mobile phone films being seen as an emerging genre, this project lends itself well to the creation of ‘new’ and ‘original’ products - in fact, all students felt that they had been creative and innovative in their projects. The re-interpretation of originality which underpins remix culture also featured strongly, whether through sampling (in the case of the David Lynch quote at the beginning of the film “Life Cycles” or through reinterpreting the work of others (in the case of “MOAR House and Whatever”, which was a remake of a house track using household objects). If we consider the films as creations that are new, original and having value, then it is important to consider personal value versus domain value.

One of the most successful films (according to Youtube views/ratings and class response) in 2010 (MOAR House and Whatever) received over 4000 views, 3 YouTube awards and 7 pages of comments in 24 hours, all of which were highly positive. This response and the unwillingness of groups to identify the work as a ‘student project’ underlines the experience of students as legitimate members of an external community such as YouTube. As a piece of open content produced by students, this will serve as an inspiring example for future cohorts (it will be interesting to observe the influence of this film) and has also been lauded by a senior producer for a major broadcaster.

In contrast to this, one of the films rated as the best by the class in 2009 (“The Move”) received only one YouTube comment on its release, which was negative. It was interesting to note the reaction of the 2010 group when being shown this 2009 film in class. They noticed the negative comment on YouTube and this influenced their attitude towards the film, as they considered it to be low in domain value. This was in sharp contrast to the 2009 cohort, who were not influenced by its reception on YouTube and rated it as being the best film produced across the whole group. Stylistically it played on the graininess and low-fi quality of the camera which added to the verisimilitude of the film – however people viewing the film out of context as a single YouTube upload (the invisible audience) were not aware of this and rated it as being low quality. The 2010 cohort veered away from this style after seeing the YouTube comment, even though the 2009 cohort had rated it highly, knowing the context of the film and the rationale for the amateur footage style. These experiences put the classroom and YouTube communities into contrast.

Transformation

Kleiman(2008) highlights risk-taking, chance (encountering and exploiting), serendipity and opportunity as factors that influenced creativity as a transformation-focused experience. The mobile phone, by its very nature as a pervasive, accessible, unobtrusive recording medium, lends itself to creativity through chance encounters and this is something that is evident in 11 out of the 13 films produced. The authenticity of serendipitous footage can be seen as being a characteristic of the genre, although the ease of recording authentic footage does raise issues around copyright and ethics and these had to be addressed by the students in order to publish their work openly online. The act of filming on a mobile phone did enable students to move beyond the technology and think more imaginatively. One student confirmed that he was inspired to creativity by filming with his phone, looking at the world through the ‘eyes of my phone’, liberated by its portability and inconspicuous nature. Another student felt liberated by the freedom to film shots unbound by video production norms.

Serendipity lay at the heart of the more memorable aspects of many of the films, such as quotes from people in the street, or sound samples being remixed and reused: in one of the films, a sound sampled from an unusual instrument played by a busker became the musical theme for the entire soundtrack. Risk-taking also featured in many films, mainly in terms of how the phones were actually used in the filming process: attached to sledges, zip wires and skateboards before being propelled at great speed, the students felt able to take these risks as they were using their own devices.

While intended to be a complement to more traditional instruction in video production, there does seem to be some evidence from student comments - and in line with (Kleiman, 2008) that in this sense the creative freedom of the project may have had a “positive yet disruptive, disorienting force.... the potential to disturb and even threaten educational and pedagogic structures, systems and processes.”

Fulfillment

Fulfillment as personal commitment and a sense of achievement was clearly demonstrated by the students throughout the project, and was evident in the evaluation, blog-based reflections and observations. A student confirmed that the learning acquired from editing video had inspired him to make video for tracks he made – his own and found video. Another reported that he had purchased a FLIP Mino HD Camera for future experimentation. A sense of enjoyment came through in their comments.

They welcomed the opportunity to develop their skills in the production of short-form content, seeing this as something that is relevant for them as future production professionals and they clearly felt a sense of satisfaction and achievement. One student from a mainly audio background became so interested in the process of syncing the video with the audio of the original that he is considering editing music videos as a future career.

After completion of the project/module, many students have carried on making films using their mobile phones and have begun to engage more seriously as producers in the YouTube community. It seems that the mobile film project has had a genuinely transformative effect on many of the students, both personally and professionally.

Creativity and OERs

There were two major expectations of the students doing their projects, openness (this was encouraged not enforced) and the use of mobile phones for filming that enabled the students to produce ‘little OERs’. These expectations can be viewed as constraints. In publishing films within the YouTube community unacknowledged as student project work, the groups engaged in an authentic knowledge sharing and participatory pedagogies (Brown & Adler, 2008). Rather than restricting themselves to classroom ‘communities’, students were keen to engage in the YouTube community where their presence and identity can transcend their temporary roles as students, and they own their own work. In this setting, they are producing open media resources rather than specifically OERs. The 2010 cohort were interested to see how the 2009 videos fared on YouTube, and the previous films provided good teaching and discussion examples. The strongest experiences here were product- and fulfillment-focused. Some students clearly had transformation-focused creative experiences, considering different career paths, challenging disciplinary orthodoxies.

However, student experiences of creativity were variable and difficult to tease out whilst students are being assessed when they may feel that claiming creativity is expected and beneficial to their assessment outcomes. Certainly the blogs, wikis, and Flickr images were generally regarded as records of process, of interest for assessment rather than as persistent artifacts.

Conclusions

- The analysis using Kleiman’s framework does reveal that students have experiences of creativity that may be triggered by constraints, experienced through the process of developing a product, leading to personal transformation and fulfillment. We found that Kleiman’s framework fitted student experiences: the opportunities designed into the assessed task were realised by students. Therefore, academics wishing to incorporate activities leading to creative experiences for students can benefit from using Kleiman’s framework.

- The dimension of openness worked in different ways. We have found a link between the tutor modeling/projecting the idea of openness and creativity and students experiencing it (or not). In this project students were introduced to films produced by a recognized media innovator and their subject tutor (and in 2010, prior students’ mobile film productions), along with other YouTube resources as inspirational learning artifacts and triggers for working beyond the constraints of the medium. The link between mobile phone films and the ‘good enough’ movement (Engholm, 2010) was apparent. However despite the acceptance of imperfection in participatory culture (Gauntlett, 2011) some students struggled to accept this, and did not always fully embrace the more accidental aspects of the medium.

- Students did produce and consume OERs, although openness of resources operated differently for different media. Creativity was evident in the student-produced films themselves but less apparent in other platforms. Records of group processes such as the wikis were more important for formal education purposes i.e. assessment, while the blogs enabled individual reflection which may be considered less important as OERs as they were linked to expressions of fulfillment. The films themselves were most significant in terms of creativity. This reflects earlier findings of student use of computer-mediated communication in that media came to occupy their own niche (Haythornthwaite, 2001).

- Self-conscious reference to creativity may be engendered by assessment requirements rather than a free expression of students’ experiences. ‘Creative freedom’ was the most common theme that emerged in the evaluations, although much of the feedback (evaluation questionnaires, blog-based reflections) tended to reflect what they had been told in class or what was stated in the assessment brief. Emphasis had been placed on the potential for mobile phone filmmaking practice with regard to innovative, imaginative, creative techniques – in fact this was a requirement of the assessment. The majority of student responses and reflections acknowledged their appreciation for the extended scope for creativity in this project, however these responses may also have been reflective of an assessment-driven approach, a desire to please the assessor. At the same time, their engagement with their mobile phones as tools for production did appear to stimulate the creative process, as they were both freed from the constraints of ‘traditional’ practice while simultaneously having to work around the constraints of the new medium.

- Tensions exist between the need for scaffolding and frameworks and the removal of constraints that temper creativity and authenticity. As shown in Fig.1, their engagement with the four platforms (YouTube, wiki, blog, Flickr) varied and they viewed only YouTube as the ‘public’ space - this would be the space that they would make publicly available to their friends through sharing via Facebook and other social network services. The majority of students portrayed themselves as YouTube publishers rather than students.

- The impact of authenticity and publication on creativity was evident. The constraints of the medium (mobile phone) challenged the students to develop workarounds, innovative practices and practice creative ways of thinking (Jackson, 2002). This particular learning activity did not stifle creativity (Robinson, 2007) but actually promoted it. The students experienced creativity as a social process (Gauntlett, 2011). Most importantly, the phones belonged to them personally unlike the other platforms. The novelty, ubiquity, and freedom of using their personal devices in this way appeared to free them constraints and structure, unlike the online platforms, which by design tend to dictate the form and the structure of the product.

- The production of open media resources that have a dual function as OERs has clear benefits in terms of knowledge sharing and community participation (YouTube success may inspire others) and also drawbacks (in-class discussion may be hampered by a negative YouTube community reaction).

- Transformation in the short term was evident in participants but a longitudinal study is needed to measure any long-term impact on practice. A limitation of the current study is that it is not possible to say what external impact - if any - the productions have as open media resources or OERs. However, the consumption of student OERs by later cohorts legitimizes their own productions as OERs. Furthermore, a core benefit of open publishing is that possible future problems regarding copyright, attribution etc. can all be resolved so that a growing body of student work becomes available as an archive for as yet unknown uses (although unknown uses also risk removal of context). However, even if the wider impact of student-produced OERs is limited, the impact of producing OERs can be significant to the practice of students now and in the future, with their acknowledgement of the status of OERs and their improved skills and knowledge in copyright and attribution.

- Further work is needed to explore in detail the relations between OERs and creativity. While there is a clear link between academics’ perceptions and student experiences, the links between OERs and constraints are less apparent. Future work will include detailed focus groups and further analysis of the relations between student-produced OERs, creativity and practice, once assessment is no longer present as a potential influence.

References

- Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context : update to The social psychology of creativity. Boulder, Colo. ; Oxford: Westview Press.

- Baker, C., Schleser, M., & Molga, K. (2009). Aesthetics of mobile media art. Journal of Media Practice, 10(2&3), 101-122.

- Baskerville, R. (1999). Investigating Information Systems with Action Research. Communications of the AIS, 2(19). Retrieved October, from

- Brown, J. S., & Adler, R. P. (2008). Minds on fire: Open education, the long tail, and learning 2.0. Educause review, 43(1), 16.

- Browne, J. (2010). Securing a sustainable future for higher education: an independent review of higher education funding and student finance. Retrieved from http://hereview.independent.gov.uk/hereview/report, from www.independent.gov.uk/browne-report

- Checkland, P., & Holwell, S. (1998). Information, Systems and Information Systems: making sense of the field. Chichester: Wiley.

- COMSCORE (2010). UK Leads European Countries in Smartphone Adoption with 70% Growth in Past 12 Months. Retrieved 3 March, 2011, from http://www.comscore.com/Press_Events/Press_Releases/2010/3/UK_...Months/.../eng-US

- Dewey, J. (1998). Experience and education (60th anniversary ed. ed.). West Lafayette, Ind.: Kappa Delta Pi.

- Downes, S. (2007). Models for sustainable open educational resources. Interdisciplinary journal of knowledge and learning objects, 3, 29-44.

- Engholm, I. (2010). The good enough revolution—the role of aesthetics in user experiences with digital artefacts. Digital Creativity, 21(3), 141-154.

- Gauntlett, D. (2011). Making is connecting : the social meaning of creativity, from DIY and knitting to YouTube and Web 2.0. Oxford: Polity Press.

- Hall, M. (2010). Tuition fees, markets, and inequality. In Professor Martin Hall. Vol. 2011. Salford:(University of Salford).

- Haythornthwaite, C. (2001). Exploring multiplexity: Social network structures in a computer-supported distance learning class. Information Society, 17(3), 211-226.

- Hoyle, M. (2009). OER and a Pedagogy of Abundance. In E1n1verse – WoW, Learning, and Teaching. Vol. 2011.

- Hylén, J. (2007). Giving Knowledge for Free: The Emergence of Open Educational Resources. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

- IIEP (2005). UNESCO’s International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP) Forum on Open Educational Resources/Open Content. Retrieved 8 April, 2006, from http://www.unesco.org/iiep/virtualuniversity/forums.php, from https://communities.unesco.org/wws/info/iiep-oer-opencontent

- Jackson, N. (2002). Guide for Busy Academics: Nurturing Creativity. (LTSN Generic Centre).

- Jackson, N., & Shaw, M. (2005). Subject Perspectives on Creativity: a preliminary synthesis.

- Kember, D., Ha, T. S., Lam, B. H., Lee, A., Ng, S., Yan, L., et al. (1997). The diverse role of the critical friend in supporting educational action research projects. Educational Action Research, 5(3), 463-481.

- Kleiman, P. (2008). Towards transformation: conceptions of creativity in higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 45(3), 209-217.

- Knight, P. (2002). The idea of a creative curriculum. Retrieved February 24, 2010, from http://www.palatine.ac.uk/files/999.pdf

- Knudsen, E. (2010). Cinema Of Poverty: Independence And Simplicity In An Age Of Abundance And Complexity. In Wide Screen Journal.

- Kupferberg, F. (2003). Creativity is more Important than Competence. In Fremtidsorientering. Vol. 2003.

- Lanzara, G. F. (2010). Remediation of practices: How new media change the ways we see and do things in practical domains In First Monday. Vol. 15.

- Leonard-Barton, D. (1995). Wellsprings of Knowledge.Building and Sustaining the Sources of Innovation. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA., 1995.

- Loveless, A. (2002). Literature review in creativity, new technologies and learning.

- Mumford, E. (2001). Advice for an action researcher. Information Technology & People, 14(1), 12-27.

- Oates, B. J. (2004). Action research: Time to take a turn? In B. Kaplan, D. Truex, D. Wastell, T. Wood-Harper & J. I. DeGross (Eds.), Information Systems Research. Relevant Theory and Informed Practice (pp. 315-333). Boston: Kluwer.

- Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2001). Introduction: Inquiry and Participation in Search of a World Worthy of Human Aspiration. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of Action Research. Participatory Inquiry & Practice (pp. 1-14). London: Sage.

- Robinson, K. (2007). Out of our minds: Learning to be creative: Wiley-India.

- Runco, M. A. (2008). Creativity and Education. In New Horizons in Education. Vol. 56.

- Sefton-Green, J. (1999). Young people, creativity and new technologies : the challenge of digital arts. London: Routledge.

- Stacey, P. (2007). Open educational resources in a global context. First Monday, 12(4), 5.

- Susman, G., & Evered, R. (1978). An Assessment of The Scientific Merits of Action Research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(4), 582-603.

- Walsh, C. S. (2007). Creativity as capital in the literacy classroom: youth as multimodal designers. Literacy, 41(2), 79-85.

- Weller, M. (2010). Big and little OER. Open Ed.

[1] A smartphone is a mobile phone that combines aspects of computers, phones and cameras. They run operating systems that provide a platform for application developers to offer applications that improve the usuability and functionality of the phone beyond what is available through the purchase of the phone itself.

[2] Platform agnosticism (in technology) is generally used to refer to an application that will run on any computer operating system. In this context, we use the term to describe an approach where students are free to produce and publish media on any platform of their choice.

[3] Weller publishes his paper at a Conference and stores it in the Open University repository Open Research Online, both of which have explicit quality criteria (big OER), using the concept of big and little OER that he acknowledges from Hoyle’s blog post (little OER).