Teachers’ Perceptions of Teacher-Student Relationship in Distance Education

Arnon Hershkovitz [arnon.hershkovitz@gmail.com], Akiva Berger [bergerakiva@gmail.com], Tel Aviv University, 30 Haim Levanon St., Tel Aviv 6997801 [http://www.tau.ac.il], Israel

Abstract

In this qualitative study (N = 4), we explore teachers’ perceptions of teacher-student relationship in distance education. Participants were teaching in both distance- and traditional classrooms, and we took a within-subject approach in order to highlight the differences in relationship between the two settings, with each participant being interviewed twice, using the Teacher Relationship Interview (TRI) protocol. TRI is focused on the teacher’s relationship with a single student chosen by the interviewed teacher. Findings suggest differences in the ways our participants perceived their students and communicated with them. Specifically, participants chose to be interviewed about distant students who were academically successful and about traditional classroom students who were generally struggling. Additionally, when referring to relationship with the distant students, it was mostly about issues directly related to the material taught, while regarding the traditional classroom student, there was a more comprehensive look at the relationship. Interestingly, there was emphasis on communication means and practices only when referring to the distant student. Finally, according to the participants, text-based communication – on which they were mostly relying – may impact teacher-student relationship in different ways.

Abstract in Spain

En este estudio exploratorio (N = 4), estudiamos las percepciones de los profesores acerca de la relación profesor-estudiante en la educación a distancia. Los participantes enseñaban en aulas de clase tanto a distancia como tradicionales, y hemos adoptado un criterio dentro del sujeto para destacar las diferencias en las relaciones entre las dos configuraciones, en donde cada participante es entrevistado dos veces, usando el protocolo de Entrevista de Relación con el Profesor (TRI – Teacher Relationship Interview). El TRI se enfoca en la relación del profesor con un solo estudiante, elegido por el profesor entrevistado.

Los hallazgos sugieren que hay diferencias en las maneras en que nuestros participantes percibieron a sus estudiantes y se comunicaron con ellos. Específicamente, los participantes prefirieron ser entrevistados acerca de estudiantes a distancia que fueron exitosos académicamente y acerca de estudiantes de aula de clase tradicional que por lo general debían esforzarse.

Además, al referirse a la relación con los estudiantes a distancia, era por lo general respecto de los temas directamente relacionados al material enseñado, mientras que con respecto a los estudiantes del aula de clase tradicional, había una visión más comprensiva de la relación. Curiosamente, se hizo hincapié en los medios y prácticas de comunicación solamente cuando se referían al estudiante a distancia. Finalmente, según los participantes, las comunicaciones basadas en texto — en las que se confiaban mayormente — podrían impactar la relación profesor-estudiante de maneras diferentes.

Abstract in Hebrew

במחקר גישוש זה (N = 4), אנו חוקרים תפיסותיהם של מורים את יחסי מורים-תלמידים בלמידה מרחוק. המשתתפים לימדו הן מרחוק והן בכיתה מסורתית, ובאמצעות מערך מחקר בין-נבדקי איתרנו את הדומה והשונה בין תפיסותיהם את יחסי מורים-תלמידים בשתי התצורות; כל משתתף רואיין פעמיים באמצעות פרוטוקול Teacher Relationship Interview – פעם אחת לגבי כל תצורה – במהלכו מתאר המורה את יחסיו עם תלמיד אחד מכיתתו, לבחירתו. מן הממצאים עולים הבדלים באופן בו תפסו המורים את תלמידים ובאופן בו תקשרו איתם. בפרט, בנוגע לכיתה המרוחקת - המשתתפים בחרו להתייחס לתלמידים שהצטיינו מבחינה אקדמית, בעוד בנוגע לכיתה המסורתית – בחרו המשתתפים להתייחס לתלמידים מתקשים. בנוסף, בהתייחס ליחסיהם עם התלמידים המרוחקים, התבטאויות המשתתפים היו בעיקר בנוגע לחומר הנלמד, ואילו בהתייחס ליחסיהם עם התלמידים בכיתה המסורתית ניכר מבט רחב יותר על מכלול היחסים עימם. מעניין היה למצוא כי רק בהתייחס לכיתה המרוחקת הדגישו המשתתפים נושאים הקשורים לפרקטיקות של תקשורת. לסיום, על פי המשתתפים, תקשורת מבוססת-טקסט (בה השתמשו בעיקר) עשויה להשפיע על יחסי מורה-תלמיד בדרכים מגוונות.

Keywords: student-teacher relationship, teachers’ perceptions, Web conferencing

Introduction

Teacher-student interpersonal relationships are key to students’ academic, social and emotional development, and may consequently affect social and learning environments of classrooms and schools (Birch & Ladd, 1998; Cornelius-White, 2007; Gregory & Weinstein, 2004; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; 2006; Sabol & Pianta, 2012). On the one hand, strong, supporting student-teacher relationship may promote students’ feelings of safety, security and belonging, which, in turn, will lead to higher academic achievements. On the other hand, conflictual student-teacher relationship may decrease students’ engagement with school’s academic and emotional resources, and may lead them to failure (Hamre & Pianta, 2006; Roorda, Koomen, Spilt, & Oort, 2011). Importantly, positive or negative teacher-student relationship may also influence teachers’ well-being and professional development (Hamre, Pianta, Downer, & Mashburn, 2008; O’Connor, 2008; Roorda et al., 2011; Spilt, Koomen, & Thijs, 2011; Yoon, 2002). Hence, the relationship between teachers and students are key to classroom research (Pianta & Hamre, 2009).

Teacher-student relationship is a complex construct. Traditionally, these relationships are defined by a three-dimensional model, which refers to positive aspects, negative aspects, and aspects related to the actual help students get from their teachers (not necessarily academic, might also be personal, emotional, etc.). These dimensions are often termed Conflict, Closeness/Satisfaction, and Dependency/Instrumental Help, respectively (Ang, 2005; Pianta, 1992). Like any other interpersonal relationship, teacher-student relationship is affected by a host of factors, including personal characteristics (of students and teachers) and contextual. Distance education is not a different kind of education, and what is known to be effective in education is also applicable to distance education (Simonson, Schlosser, & Orellana, 2011); therefore, teacher-student interactions and relationship are also crucial in distance education (Bergström, 2010; Santally, Rajabalee, & Cooshna-Naik, 2012; Shin, 2003; Xiao, 2012).

Traditionally, distance learning supports one-way communication from the teacher to the students. This holds true for many distance learning settings, starting from the old, television-based or mail-based distance teaching, and until today’s Massive Open Online Courses; therefore, power relationship might be inherently prominent in distance education (DePew & Lettner-Rust, 2009). A change in the practices of teaching and learning, i.e., implementing new pedagogies from distant, may help in levelling these relationship (Bergström, 2010; Lai, 2017; Shin, 2003).

Interaction and communication are key to the initiation and development of interpersonal relationship. As they are inherently different in distance education than in traditional settings of teaching and learning, interaction and communication between students and teachers have been a prominent field of study in the context of distance education (Bozkurt et al., 2015). Communicating and interacting from distance takes into account the idea of social presence – in some way, an extension of our understanding of physical presence – which is mostly situated in the context of behavioural engagement, that is, strongly associated with student-teacher relationship (Tu & McIsaac, 2002; Xin, Youjia, & Barbara, 2015). Furthermore, text-based communication – the basis of many configurations of student-teacher communication from distance – may have an important social role in learning and teaching (Lapadat, 2006). Therefore, the main purpose of this study is the investigate teachers’ perceptions of teacher-student relationship in distance teaching – in a configuration where synchronous web conferencing and asynchronous discussion groups take place – compared with traditional teaching.

Methods

Participants and Research Field

Participants were four experienced Israeli middle- and high-school teachers (three females, one male), 39-62 y/o, with 15-35 years of experience in teaching, and 3-5 years of experience in distance-teaching. Participants teach in an online school that offers courses on Jewish-related topics to Jewish schools in the United States. This service is used by small Jewish communities that cannot find, or cannot afford, teachers in their vicinity. These courses combine synchronous and asynchronous meetings. During the synchronous lessons – which normally take place every other week and last an hour – teaching from distance is done using Blackboard Collaborate™, with the school children taking the class from their school; using this software, teacher can use many features, like showing their presentation to students, take surveys, or engage the students with writing on a virtual board. The asynchronous meetings include online discussions, collaborative tasks, and consuming various resources. Often times, one course is given to children from a few schools. A typical course will have 10-15 students.

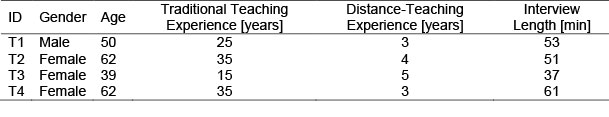

In addition to teaching in this online school, the participants also teach in traditional schools in Israel. This allows us to compare between their perceptions of teaching from distance and traditional teaching. See Table 1 for information about the participants.

Design

If order to better understand participants’ perceptions of teacher-student relationship in distance learning, we took a qualitative, within-subject approach, with data collected using semi-structured interviews. Interviews’ full scripts were qualitatively analysed using the conventional content analysis approach, where coding categories are derived directly from the text data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The themes were identified using an iterative process, in which both authors took part, moving from low-level codes to a coherent, high-level scheme (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008; Mayring, 2000), with basic unit of analysis being an interviewee’s statement. Overall, four main themes, under two categories, were identified, and they are presented in the Findings section.

Instruments

Interviews followed the Teacher Relationship Interview protocol (TRI; Pianta, 1999). This is a semi-structured interview which discusses teacher-student relationship with an individual student. At the beginning of the interview, the participant is choosing a current student of them, and later in the interview refers to this student. The interview is mostly focused on critical moments in the relationship with the student, and it does so by referring to specific incidents, rather than to general perceptions. Naturally, as deviations from the protocol are allowed, and as we wanted to get as much interesting insights from the interviewed teachers, we let them talk about their students in general (if they wished to), and they sometimes made comparisons between the two teaching settings and not referred to them solely separately.

At the beginning of the interview, the interviewee is asked to choose three words that tell about their relationship with the child, and to tell about a specific experience that describes each word. Next, the interviewee is asked to tell about times when she or he and the child “clicked” or were not “clicking”. Later on, the interviewee is asked, regarding that child, about challenging social and academic experiences, about their reaction to the child’s misbehaviour or help-seeking, and about doubts about meeting the child’s needs. Finally, the interviewee is asked whether she or he were thinking about the child when they are at home, about their relationship with the child’s family, and about satisfactory experiences with the child.

Procedure

Interviews were conducted via video conferencing, using Zoom™. Interviews were recorded and were later fully transcribed. As teacher-student relationship are highly personal and depends on the characteristics and on the educational agenda of the teacher, we took a within-subject approach, interviewing each participant twice - first, regarding a child from a class they teach face-to-face in Israel, then regarding a child from a US-based class they teach from distance. This way, we were able to compare between the two settings.

Table 1: Summary about the research participants

Findings

We found four main themes regarding teacher-student relationship, under two categories. The themes are fully described here below. For purposes of convenience and clarity, we will consistently use the terms distant classroom, distant student, traditional classroom, and traditional classroom student to refer to the different classes, students.

Points of Reference

Overall, it seems that there were very different attitudes towards the children to whom our participants referred regarding the two educational settings. This was evident by the motivational characteristics of the student and by the nature of the caring and closeness discussed, which are described by two themes.

Chosen Distant Students Are Academically Successful, Chosen Traditional Classroom Students Are Academically (or Otherwise) Struggling

Interestingly, when referring to the distant classroom students, all participants chose students who were academically successful, demonstrated either by their motivation to learn or by their high intellect:

“[He is] so intellectual, we often communicated assignments that have been turned in, so it was an interchange of ideas through the work that the student did.” (T1, M:50)

“Part of the online thing is they fill out a survey after every unit, and he always says ‘amazing unit! Can’t wait for the next one!’ […] It’s just this very nice dialogue about his usual enthusiasm about the course” (T2, F:62)

“She was just so enthusiastic […], she was so on target, she was very very excited and enthusiastic […].I hope she doesn’t get discouraged, and she doesn’t, she never gets discouraged, if a live session went badly she was still, she wasn’t bored, she didn’t get frustrated” (T3, F:39)

“She takes the work very seriously, she also initiate questions, if there is something she doesn’t understand, she’d write to me, she asks what she can do. If I’m asking to write what they did today, she writes to me […]. Yes, there are students like this.” (T4, F:62)

The last remark of T4 (“Yes, there are students like this”) emphasizes that not all students are like the one she was referring to, that this behaviour is not common among the students she knows. Hence, her chosen student was one who is uniquely enthusiastic about learning.

In contrary, regarding the traditional classroom student, participants chose a student who was generally struggling, or who was not motivated to learn. For example, while describing the term disappointment, which was one of the three words describing her traditional classroom student, one of the participants said:

“Many hours of conversations, meetings with teachers – did not bring about the expected outcome, mainly regarding her motivation and cooperation” (T4, F:62)

Similarly, another participant described her student as

“seemingly uninvolved with the course, not engaged” (T2, F:62),

and another one, regarding the traditional classroom student he was referring, was

“not sure that intellectually at that moment in his life he was actually able to […] handle the texts” (T1, M:50).

Interestingly, some of the chosen traditional classroom students were struggling non-academically, like in the case of one of the participants who mentioned, regarding her traditional classroom student, that

“she is really struggling with who she is” (T3, F:39).

Regarding Distant Students as Students, Regarding Traditional Classroom Students as Persons

Regarding the distant students, it was mostly about issues directly related to the material taught. For example:

“She knows that I care, she will always write ‘thank you for understanding, thank you for caring, thank you for letting me hand something in late, thank you for being so flexible’. So she, I think, she knows that I care and that my goal is for her to love class and to learn something” (T3, F:39)

However, regarding the traditional classroom student, these instances were not limited to school-related aspects of their relationship. Note how the same teacher refers to her traditional classroom student:

“Because of our respect for each other, we really cared about each other, we were very close, she could come to me… She was very concerned about a student who was having a really bad relationship with the administrator and she came and talked to me about it” (T3, F:39)

For another participant, this difference is prominent. Recall the importance of the phone call one teacher made to her distant student. Even this critical moment of their relationship was initiated by academic reasons:

“Yeah, also caring […]. He asked me a question and I wanted to tell him the answer, I wanted to give him some further insight and I thought it would be better for me to call and it ended up being a very positive experience and made a huge impact” (T2, F:62)

However, when the same teacher referred to her traditional classroom student, she mentioned other aspects of closeness:

“She and I walked together to my house. That was very deliberate on my part […]. And […] the conversation that became very personal about her life, her challenges, her family stuff, like that, and that was a really great conversation” (T2, F:62)

This difference is also prominent in the references of T4 (F:62) to the moment of “click” with her students. While this moment with the distant student was “when [the content] was really difficult for her for the first time”, the “click” with the traditional classroom student was “when she felt she could rely on me”. Consequently, these moments yielded very different routes of support, that were mostly academic for the distant student (first quote) and much more comprehensive for the traditional classroom teacher (second quote):

“We did one-on-one [via Blackboard Collaborate] together, and we talked, and since then I could tell her: ‘if there’s something that you don’t understand – let’s talk’” (T4, F:62)

“Then she shared with me more and more about what was going with her generally […], she noticed that I wanted to be part of her life, that I talked with people that has to do with her life out of school” (T4, F:62)

The fourth participants’ experiences of “clicking” with the students regarding to whom he chose to be interviewed, also demonstrate this difference. Regarding the distant student, the click started when the student “turned in an assignment where he was using an artistic representation”; although this moment made the teacher understand that the student “expressed emotions and spiritual connection”, the connection with the student was as strong as to push him more “to understand the text” (T1, M:50). When asked to describe a “click”-moment with the traditional classroom student, this teacher said: “We clicked over his illness, getting to know his special needs over a trip”, which barely has to do with the academic aspects of the learning experience.

Even when talking about relationship with the student’s family, these differences are prominent. While regarding her connection with the distant student’s family, T4 (F:62) told that “in this classroom I hold a meeting with the parents, and I write emails to the parents, if I notice that a student is not doing the assignments – I send an email, sometimes we send updates about what we did this week”. However, when she refers to her connection with the traditional classroom student’s family, she describes it as “intensive, like any teacher who needs to report, to ask, to stimulate, in the learning level as well”.

This distinction is also evident when teachers talk about their most satisfying moments with their students. Referring to the distant student, this satisfaction is, as above, mostly about academic issue. Note the emotional expressions of one of the teachers when she describes her satisfaction with her distant student:

“The most satisfaction is […] when I read her discussions. Her discussions are more creative because they are more emotional, but they are not emotional based on just emotion, but they are emotional based on what she read, what she absorbed, and what she employed from the readings, but they really give me a key to her soul, her passion, her passion comes through in her discussions and in her reflections, I love her reflection questions, I love her reflection questions, because that’s when […] she puts herself in the place of characters and how she would deal with the situation, and I get to see how […] personality really comes through” (T3, F:39)

Similarly, when another teacher talked about the most satisfying moment regarding her distant student, she said:

“She went through an amazing process. At the beginning of the year, she was very pressured, and now, as a student, I think she really feels comfortable with what she’s doing” (T4, F:62)

But when referring to the most satisfying moment regarding her traditional classroom student, she said:

“The fact that I could be with her together, along different stages […], this felt good, that she let me being a partner to what she went through” (T4, F:62)

Similarly, when T2 (F:62) referred to the most satisfying moment with the distant student, it was about “his engagement and his enthusiasm”, and regarding the traditional classroom student, it was about “accepting her for who she is and finding a way into her heart and mind”.

This difference in points of reference was brilliantly put by one of the participants, who said, referring to Ethan, his distant student, and Johnny, his traditional classroom student:

“I think of Ethan the person, I think of Johnny the student” (T1, M:50)

The Medium Is the (Complex) Message

Many references were done regarding the very nature of the online medium, comparing it with the traditional classroom setting. This allows us to highlight both benefits and challenges that are prominent in the online setting.

Communicating from Distant is Central to Teacher-Student Relationship

Interestingly, there was emphasis on communication means and practices only when referring to the distant student.

The very fact that the distant students were communicating with their teachers in a specific way was noted by the participants. For example:

“Immediately when she doesn’t understand something or something is going to be late or she really loved something, she will write it back to me, she will send an email, she will write it back to me, she will let me know how she feels, what’s going on in her life, why she can’t complete something on time, and how she loved this last assignment that she had” (T3, F:39)

Another participant mentioned that the distant student to whom she referred tends

“to talk too much so I need to limit his verbosity” (T2, F:62).

Particular references were also highlighting non-communication between the student and the teacher, for example:

“When there wasn’t assignments to be given in to be graded, there didn’t seem to be any communication, so it might be two weeks between communications […] He would turn in some work, I would grade it, but there was no interaction, there was nothing for us to really talk about” (T1, M:50)

Later in the interview, this teacher mentioned that

“as soon as the course ended, I have never heard from him since” (T1, M:50).

Contrary to that, when referring to the traditional classroom, no mentions at all were done to the ways students communicated (or not communicated) with their teachers.

Going further than merely mentioning the communication with their distant students, the participating teachers also mentioned the specifics – maybe even the mechanics – of this communication and how they impacted the relationship between the teacher and the student. For example, talking about a phone call she held with her student, one of the participants said:

“I think in terms of impact, the phone call I made to him happened in the very beginning of the year and I think that had a huge impact on him and our relationship, because maybe all our subsequent report that we had I think was built on that phone call” (T2, F:62)

Another participants specifically referred to the contribution of written communication with the student:

“It’s interesting that in the communication, in our written communication, I also get to know her, I mean, she also writes: ‘How are you? When will come to visit us? It was very nice’. That is, I feel that I can also get details from her that are not related solely to the learning, via our correspondence” (T4, F:62)

Note how another participant described his communication with the distant student to whom he was referring, and how detailed he was in telling about it:

“Informality. The tone of conversation was very light […], there was a comfortable, there seemed to be a rhythm to the conversation from early on in the engagement with the student” (T1, M:50)

Such a specific description is also brought by T2 (F:62), who mentioned that the writing of her distant student was “so immediate and impulsive that it brings him alive […], because so often there are exclamation points and five question marks, so he’s a real presence in his written communication”. Notably, she compared between his verbal and textual expressions, and said that

“verbally he is enthusiastic, but it’s almost more powerful in his [written] words […], somehow reading it is almost more powerful than hearing it” (T2, F:62).

Another participant, referring to the emails she was writing to her students, said that

“you got to invest that time in email, and you have to choose your words carefully in email too” (T3, F:39).

Similar reference to email-writing was done by her, however with regarding to the distant student about whom she was talking, while emphasizing the benefits of writings:

“The beauty of the online is that the only way that she can let me know how she feels is by writing to me, which she wouldn’t necessarily say, she might not be so reflective of an idea in a face to face […] Whatever comments she would make, maybe in a class discussion it would come out, but the fact that she commits it to paper, to writing, makes you think so much more profoundly than when you speak” (T3, F:39)

Focusing on the very communication may be understandable, as communication is the basis for developing and maintaining interpersonal relationship. As a result, teachers too may feel the need to keep some communication alive between classes. One participant mentioned that she emailed her students, explaining that

“because you don’t see [the students] often, you also feel like ‘I’ll better do it’” (T3, F:39).

Therefore, the non-continuous, non-communicative nature of distance teaching and learning negatively impacts the ability to develop relationship:

“I have one semester with this student, we met I think a total of five times online and that’s it, there’s no continuation… [Maybe if we] met more often over the course of one year [we could] develop more of a relationship […]” (T1, M:50)

“I really became a mentor to [the traditional classroom student]. I am not a mentor to [the distant student], I think that I might be if we had face to have, yeah, I think face to face really allows the student to have an ongoing relationship, much more spontaneous. And just the fact that you are there all the time” (T3, F:39)

Even more, this kind of fragmented presence in students’ school routine may make some teachers ponder about their relationship, as was clearly put by one of our participants:

“Our relationship […] was a very transactional relationship, as in: I was hired to present material, he was there to learn material, and we concluded our business. You know, I don’t feel like I miss the cab driver after I got out of the cab.” (T1, M:50).

Text-Based Communication May Promote or Hinder Teacher-Student Relationship

According to the participants, the way the learning is facilitated from distance may impact teacher-student relationship. Online, most of the teacher’s role is educational, while in face-to-face settings, other factors come into account:

“While online, you are net with the kids […], but when you stand in front of kids in the classroom, there is something very intensive and difficult in their anger and frustration, I think there is something very difficult, exhausting. Online, the work is much cleaner” (T4, F:62)

If not already clear, this teacher also emphasizes that online,

“there is no educational issue, it doesn’t exist at the personal or psychological levels, meaning that you don’t see a big picture of every child […]. When you’re a teaching in a classroom, it’s not clean, it’s not net, it’s a full educational engagement” (T4, F:62).

That is, the online environment may assist the teacher academically, and the reliance of digital communication has some clear benefits for teachers:

“If there’s a student who doesn’t do what she or he needs to, so I think it’s easier in the online, you don’t have to look for him during the break, there’s a very clear type of communication” (T4, F:62)

However, the other side of that coin—i.e., that this kind of communication is hindering learning and teaching—is also sometimes evident. Text-based communication may not easily transfer students’ feelings and may not allow teachers to best handle affective aspects of their teaching:

“Lots of the information you get from online students is by reading what they write, it’s not like in a classroom, where you can say, ‘ok, I see that he’s bored, so I’ll give him something to do’” (T4, F:62)

“Wondering if you give the [right] response to students is stronger in face-to-face, because you see the student. [You wonder:] Maybe I could have gone easier on her yesterday, maybe I shouldn’t get angry yesterday. You immediately see the results” (T4, F:62)

“Most of the communication [between us] is through the work they turn in, so it’s not that personal connection” (T1, M:50)

Another participant, referring to her distant class, put it clearly: “If I had face to face [with them], first of all seeing me all the time I could have built a better relationship with them” (T3, F:39).

Nevertheless, being afar from the students, focusing on academic-related issues solely, might have negative impact on teacher-student relationship. This may happen if students perceive the teacher as in charge only for academic aspects of the learning progress. As one of the participants told us about what happened when he wrote to his distant student, after hearing about his situation:

“I heard at some point after the course that he was significantly inalienable, I wrote to him once and the response I got was: ‘what are you writing me, you are not my teacher’ kind of thing, so I’m not sure that he ever had a sense that we were supposed to connect on a human level, like it was absolutely shocking to him that I would write to him three months later to ask him how he was feeling when I heard that he was feeling not well” (T1, M:50)

Finally, the two environments may impose different culturally-enabled behaviours. As one of the participant perceive it, although she wants to just talk with her students, it is ok to do so face-to-face, but it is often not ok to do so online:

“I think what happens online is the kids write you very honestly, they do, they write you back and they write honestly. On the other hand they aren’t as apt to ‘Hi, how are you doing…’, they aren’t as apt, they are much more practical. When you see the students day to day, they will come to you and they are much more likely to share something with you, ‘I really liked the class, can we stay after class, and talk about it?’. I don’t get that online as much, nobody will stay after they read something, nobody will spontaneously say ‘I have a question I really want to share with you’” (T3, F:39)

Another participant, referring to this lack of conversions outside the class context, mentioned that the student “don’t request” discussions beyond the class, and suggested,

“it could be kids don’t feel comfortable because it’s online” (T1, M:50).

Discussion

In this study, we explored teachers’ perceptions of relationship with students in classes which they teach from distant. Comparing these with their perceptions of relationship with students in traditional, face-to-face classrooms, we were able to identify the unique characteristics of such distant relationship. Overall, four themes arise, mostly referring to the way teachers refer to their students and to the ways by which they communicate.

Notably, teachers’ perceptions of the relationship with their distant students were mostly around academic-related issues, in contrary to the way they perceived relationship with their traditional classroom students. Part of this is explained, by our participants, by the close, intimate relationship that has been developed with the traditional classroom students, mainly a result of the frequent lessons and the physical proximity. Indeed, “ideal” teacher-student relationship are built on a continuous dialogue between the two, in a way that allows the teacher to know the student and allows the student getting guidance from the teacher (Pomeroy, 1999). While the distant communication serves as a “clean” channel, which helps teachers to focus on mere teaching and content delivering, with no disciplinary or personal issues interrupting, it is still not ideal for keeping a continuous dialogue between the lessons.

However, another explanation might be helpful here. Already 20 years ago, it was suggested that learning with technology increases students’ motivation and make them more academically engaged (McGrath, 1998), and similar findings have been repeatedly reported in recent reviews (Harper & Milman, 2016; Higgins, Huscroft-D’Angelo, & Crawford, in press). Therefore, it is possible that students’ motivation in the distant class was prominent comparing to the traditional class, which made the teachers choosing motivated students to be interviewed about in the first place. Furthermore, it was already found that teacher’s “presence” in online learning is perceived by students as contributing more to academic- and less to affective and motivational aspects of the learning (Shin, 2003). Due to the importance of affect and emotion in learning, our findings that teachers’ connection with distant students is limited to the academic aspects of learning, and that they perceive their distant students as merely students and not as whole persons, are bothering and should be further explored.

Another topic highlighted in this study is the importance of communication in distant teaching. Of course, communication is an integral, crucial component of teaching and learning and of teacher-student relationship in traditional settings (Civikly-Powell, 1999; Frymier & Houser, 2000), however it seems that communication has become even more important in distance educational settings (Trentin, 2000). These settings are usually characterized by fragmented and non-verbal communication, two factors that were frequently mentioned by our participants. Therefore, new strategies should be applied by teachers in order to compensate for the lack of immediacy and non-verbal cues, which are crucially important for the development of student-teacher relationship (Frymier & Houser, 2000; Richmond, 2002). Such strategies can be associated with the nature of the communication, rather to its frequency. For example, demonstrating self-disclosure (Song, Kim, & Luo, 2016), or encouraging non-verbal cues and student participation during synchronous videoconferences (Offir, Lev, Lev, Barth, & Shteinbok, 2004). Additionally, promoting better student-teacher relationship may be achieved by increasing teacher’s presence, for example by opening additional spaces that will help in breaking the boundaries formed around the distant classroom environment, or by the teacher keeping an ongoing caring, empathetic dialogue with the students (Lai, 2017; Murphy, Shelley, White, & Baumann, 2011; Sitzman & Leners, 2006; Velasquez, Graham, & Osguthorpe, 2013; Forkosh-Baruch & Hershkovitz, 2014). It is interesting to point out, however, to our recent findings according to which student-teacher communication via Facebook was associated with some improvement in students’ perceptions of student-teacher relationship but not with teachers’ perceptions of it (Hershkovitz & Forkosh-Baruch, 2017; Abd Elhay & Hershkovitz, 2019).

Conclusion and Recommendations

By taking a within-subject approach, this study points out to some important differences in student-teacher relationship between distance education and traditional settings of teaching and learning. Summarizing our findings, we can conclude that important differences between these two configurations were found regarding teachers’ perceptions of the students and regarding the ways teachers and students communicate. These findings deepens our understanding of teacher-student relationship in distance learning. Importantly, they may assist us in thinking of ways to promote better student-teacher relationship when teaching from distance.

Above all, upon wishing to develop a strong relationship with their distant students, teachers should keep in mind two relatively simple ways of meeting this goal. First, implementing new learner-centred pedagogies is possible and recommended in distance education, just as it is recommended in traditional education, as it helps in breaking the traditional hierarchical relationship between teachers and student. Using the wide range of options enabled by today’s digital technology, it is easier than ever to change the way teaching from distance is done.

Second, teachers should recognize the need of continuous, supporting and caring communication with their students via various platforms. This way, the teacher and her or his students may be exposed to aspects of each other that are not normally present when the communication is focused solely on learning-related discussions. Consequentially, this may help in compensating for the absence of physical presence. Of course, these attempts should be responded by the students in order for them to assist in the construction of a well-connected learning community that will benefit both students and teachers.

Further research is needed for validating these findings, including studies that examine students’ perspectives of student-teacher relationship in such settings of distance education.

References

- Abd Elhay, A., & Hershkovitz, A. (2019). Teachers’ perceptions of out-of-class communication, teacher-student relationship, and classroom environment. Education and Information Technologies, 24(1), 385-406.

- Ang, R. (2005). Development and validation of the teacher-student relationship inventory using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. The Journal of Experimental Education, 74(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.74.1.55-74

- Bergström, P. (2010). Process-based assessment for professional learning in higher education: Perspectives on the student-teacher relationship. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 11(2), 33. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v11i2.816

- Birch, S. H., & Ladd, G. W. (1998). Children’s interpersonal behaviors and the teacher–child relationship. Developmental Psychology, 34(5), 934–946. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.934

- Bozkurt, A., Akgun-Ozbek, E., Yilmazel, S., Erdogdu, E., Ucar, H., Guler, E., Sezgin, S., Karadeniz, A., Sen-Ersoy, N., Goksel-Canbek, N., Deniz Dincer, G., Ari, S., & Aydin, C. H. (2015). Trends in distance education research: A content analysis of journals 2009-2013. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(1). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1953

- Civikly-Powell, J. M. (1999). Can we teach without communicating? New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 80, 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.8004

- Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113–143. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298563

- DePew, K. E., & Lettner-Rust, H. (2009). Mediating power: Distance learning interfaces, classroom epistemology, and the gaze. Computers and Composition, 26(3), 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2009.05.002

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Forkosh-Baruch, A., & Hershkovitz, A. (2014). Teacher-student relationship in the Facebook-era. In P. Isaías, P. Kommers, & T. Issa (Eds.), The Evolution of the Internet in the Business Sector: Web 1.0 to Web 3.0 (pp. 145-172). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Frymier, A. B., & Houser, M. L. (2000). The teacher-student relationship as an interpersonal relationship. Communication Education, 49(3), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520009379209

- Gregory, A., & Weinstein, R. S. (2004). Connection and regulation at home and in school: Predicting growth in achievement for adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19(4), 405–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558403258859

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72(2), 625–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00301

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2006). Student-Teacher Relationships. In G. G. Bear & K. M. Mink (Eds.), Children’s needs III: development, prevention, and intervention (pp. 59–71). Washington, DC: National Association of School Psychologists. https://doi.org/10.1300/J137v09n01_12

- Hamre, B. K., Pianta, R. C., Downer, J. T., & Mashburn, A. J. (2008). Teachers’ perceptions of conflict with young students: Looking beyond problem behaviors. Social Development, 17(1), 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00418.x

- Harper, B., & Milman, N. B. (2016). One-to-One Technology in K–12 Classrooms: A Review of the Literature from 2004 through 2014. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 48(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2016.1146564

- Hershkovitz, A., & Forkosh-Baruch, A. (2017). Teacher-student relationship and SNS-mediated communication: Student perceptions. Comunicar, 53(4), 91-100.

- Higgins, K., Huscroft-D’Angelo, J., & Crawford, L. (in press). Effects of technology in mathematics on achievement, motivation, and attitude: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633117748416

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Lai, K.-W. (2017). Pedagogical practices of NetNZ teachers for supporting online distance learners. Distance Education, 38(3), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2017.1371830

- Lapadat, J. C. (2006). Written interaction: A key component in online learning. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2002.tb00158.x

- Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.17169/FQS-1.2.1089

- McGrath, B. (1998). Partners in learning: Twelve ways technology changes the teacher-student relationship. Technological Horizon in Education, 25(9), 58–61.

- Murphy, L. M., Shelley, M. A., White, C. J., & Baumann, U. (2011). Tutor and student perceptions of what makes an effective distance language teacher. Distance Education, 32(3), 397–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2011.610290

- O’Connor, K. E. (2008). “You choose to care”: Teachers, emotions and professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.008

- Offir, B., Lev, Y., Lev, Y., Barth, I., & Shteinbok, A. (2004). An integrated analysis of verbal and nonverbal interaction in conventional and distance learning environments. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 31(2), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.2190/TM7U-QRF1-0EG7-P9P7

- Pianta, R. C. (1992). The student-teacher relationship scale. Charlottesville, VA.

- Pianta, R. C. (1999). Assessing child-teacher relationships. In R. C. Pianta (Ed.), Enhancing relationships between children and teachers (pp. 85–104). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10314-005

- Pianta, R. C., & Hamre, B. K. (2009). Conceptualization, measurement, and improvement of classroom processes: Standardized observation can leverage capacity. Educational Researcher, 38(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09332374

- Pomeroy, E. (1999). The teacher-student relationship in secondary school: Insights from excluded students. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 20(4), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425699995218

- Richmond, V. P. (2002). Teacher nonverbal immediacy: Use and outcomes. In J. L. Chesebro & J. C. McCroskey (Eds.), Communication for teachers (pp. 65–82). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., Spilt, J. L., & Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher-student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research, 81(4), 493–529. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311421793

- Sabol, T. J., & Pianta, R. C. (2012). Recent trends in research on teacher-child relationships. Attachment and Human Development, 14(3), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2012.672262

- Santally, M. I., Rajabalee, Y., & Cooshna-Naik, D. (2012). Learning design implementation for distance e-learning: Blending rapid e-learning techniques with activity-based pedagogies to design and implement a socio-constructivist environment. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 2012(2). Retrieved from http://www.eurodl.org/index.php?p=archives&year=2012&halfyear=2&article=521

- Shin, N. (2003). Transactional presence as a critical predictor of success in distance learning. Distance Education, 24(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158791032000066534

- Simonson, M., Schlosser, C., & Orellana, A. (2011). Distance education research: A review of the literature. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 23(2–3), 124–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-011-9045-8

- Sitzman, K., & Leners, D. W. (2006). Student perceptions of caring in online baccalaureate education. Nursing Education Perspectives, 27(5), 254–259.

- Song, H., Kim, J., & Luo, W. (2016). Teacher-student relationship in online classes: A role of teacher self-disclosure. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 436–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.037

- Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., & Thijs, J. T. (2011). Teacher wellbeing: The importance of teacher-student relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 23(4), 457–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y

- Trentin, G. (2000). The quality-interactivity relationship in distance education. Educational Technology, 40(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/44428577

- Tu, C., & McIsaac, M. (2002). The relationship of social presence and interaction in online classes. The American Journal of Distance Education, 16(3), 131–150. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15389286AJDE1603

- Velasquez, A., Graham, C. R., & Osguthorpe, R. (2013). Caring in a technology-mediated online high school context. Distance Education, 34(1), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2013.770435

- Xiao, J. (2012). Tutors’ influence on distance language students’ learning motivation: Voices from learners and tutors. Distance Education, 33(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2012.723167

- Xin, C., Youjia, F., & Barbara, L. (2015). Integrative review of social presence in distance education: Issues and challenges. Educational Research and Reviews, 10(13), 1796–1806. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2015.2276

- Yoon, J. S. (2002). Teacher characteristics as predictors of teacher–student relationships: Stress, negative affect, and self-efficacy. Social Behavior and Personality, 30(5), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2002.30.5.485