The Role of Subject Subculture in Teachers’ Networking in Online Communities

Anastasios Matos [tasmat@gmail.com], School Counsellor – Greek Secondary Education, Regional Centre for Educational Design [http://thess.pde.sch.gr/pekes/], Larisa, Thessaly, Greece

Abstract

In this study we trace the trajectory of one teacher’s participation in Dialogos, a digital community of practice, which has been operating for three years aiming to provide an environment for professional development towards innovation in teaching practices in the school-subject of Ancient Greek Language and Literature (hereinafter AGL-L), within the context of Greek secondary education. The case of the participant teacher we analyse here, reveals that the extent of networking in an e-community, degree centrality, developing a sense of belonging in the network and identity reconstructions, depend on socio-cultural and discursive factors, such as the school-subject culture group-members embrace (Grossman & Stodolsky, 1995). At the same time, analysis showed that meaning negotiation on the domain of interest, as well as the activity within a teachers’ digital community, is largely determined by whether community members enact identities, that are in contrast to the dominant community’s discourse about literacy.

Abstract in Greek

Σε αυτό το άρθρο μελετούμε τη τροχιά της συμμετοχής μιας εκπαιδευτικού στον Διάλογο, μια ψηφιακή κοινότητα πρακτικής που λειτούργησε επί τριετία, με σκοπό να αποτελέσει ένα περιβάλλον επαγγελματικής εξέλιξης προς την κατεύθυνση της ανανέωσης των διδακτικών πρακτικών στο μάθημα της Αρχαίας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας και Γραμματείας, στο πλαίσιο της ελληνικής δευτεροβάθμιας εκπαίδευσης. Η περίπτωση της συμμετέχουσας εκπαιδευτικού που αναλύουμε εδώ αναδεικνύει πως η έκταση της δικτύωσης σε μια ψηφιακή κοινότητα, η συνδεσιμότητα, η ανάπτυξη αισθήματος του «ανήκειν» στο δίκτυο και η ταυτοτική ανα-κατασκευή, εξαρτώνται από κοινωνικο-πολιτισμικούς και ρηματικούς παράγοντες, όπως η κουλτούρα για το γνωστικό την οποία υιοθετούν τα μέλη της ομάδας (Grossman & Stodolsky, 1995). Παράλληλα αναδείχθηκε ότι ο τρόπος διαπραγμάτευσης του νοήματος σχετικά με το πεδίο του ενδιαφέροντος της καθώς και η δραστηριότητα σε μια ψηφιακή κοινότητα εκπαιδευτικών, καθορίζονται σε μεγάλο βαθμό από το εάν τα μέλη της κοινότητας πραγματώνουν ταυτότητες, οι οποίες βρίσκονται σε αντίθετη κατεύθυνση με τους κυρίαρχους λόγους στο πλαίσιο της κοινότητας σχετικά με το γραμματισμό.

Keywords: teacher identity, digital community, networking, pedagogical discourses, subject-culture

“In ‘Dialogos’ you can keep teaching Ancient Greek with a hip-hop background or prompt students to draw information from anarchist websites … I have a different way of approaching this school-subject, so I will continue to teach it as I know and not according to the recommendations of some ‘knowledgeable’.” (Teacher, T15)

Teachers’ e-CoPs and discourses that affect connectivity

After a three-month period of his (silent and lurking) participation in the digital community of teaching practices named Dialogos (http://dialogos.greek-language.gr), teacher T15 (who is the author of the above forum post) felt that he could no longer endure being a member in the community. Mentors hold views about teaching methods and pedagogical practices, which – in his opinion – were in clear opposition to his fundamental principles regarding the teaching of AGL-L. As a result, he published his disagreement in a strong and ironic tone with the philosophy governing the principles of community and left the group. Hopefully this unpleasant episode didn’t cause any serious disruption in Dialogos, but depicted, in an explicit way, that as far as it concerns members’ interaction, participation and connectivity within the context of an e-community, there are some crucial factors to be considered, beyond those discussed in the relevant literature. Discourse is “the structured totality resulting from the articulatory practice [...] that partially restrains the meaning of certain nodal points ... but which is not subject to this fixation [...] since discourses are incomplete structures in the same undecidable terrain that never quite become completely structured” (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). Discourse is a particular way of talking about and understanding the world (or an aspect of the world) (Jørgensen & Philips, 2002).

Many factors have been identified playing a significant role in members’ high-level quantity of participation, and quality of interaction within e-communities, such as participants’ perceived sense of community (Shen, Nuankhieo, Huang, Amelung, & Laffey, 2008) and moderator’s active presence that fosters learners’ engagement, participation, and interaction (Tsiotakis & Jimoyiannis, 2016). Besides, the role of the e-community instructor / moderator is considered very important, as s/he is the key person to promote and foster online interaction and a sense of connectedness and, more specifically, his/her discussion design strategies influence the ways in which participants interact with each other and engage in discussions (Stuetzer, Koehler, Carley, & Thiem, 2013). In parallel, “digital habitat” (Wenger, White, & Smith, 2009) is a model that describes the necessary skills for implementing and maintaining a web presence, along with providing digital tools that enable moderators to facilitate groups coming together as an online community.

However, this paper copes with some key factors that interfere in the case of digital communities’ development, participants’ social presence and interconnection that, more or less, are absent in the relevant research literature. In many cases digital communities for teachers’ professional development, despite the advanced technological tools, up-to-date design principles and knowledgeable community mediation leadership, that may incorporate, do not succeed to fully engage members in the community’s social life. Factors as (competing) discourses functioning within the online group and power relations have been previously mentioned (Tusting, 2005) as playing a crucial role. When we discuss about teachers’ communities of practice, we can’t miss Bernstein’s notion of pedagogic identities (Bernstein, 2000). Basil Bernstein explains that different discourses, culturally and ideologically defined, shape different pedagogic identities and represent different approaches on teaching practices, pedagogic reformation, school subject-culture, playing thus a crucial role in teachers’ social life within digital communities.

Within the Dialogos e-community, teacher T15 enacted an identity of non-participation with a type of minimum interaction that led him to peripheral and marginal position (Wenger, 1998). Nevertheless, teachers’ T15 non-participation, is not attributed to factors as being a newcomer or luck of experience, expertise or authority within the group. As Yanow (2004) have shown, issues concerning recognition and power are decisively important regarding members’ networking in a community of practice. Similarly, Blackler and McDonald (2000; p.848) argue that the “dynamics of power, mastery and collective learning are inseparable”. Nevertheless, this is not the case as far as it concerns teacher T15, as he is a qualified teacher (holds a PhD degree in classical humanities) and has a teaching position in a selected school that is connected with the University.

Instead of attributing teachers’ deficient networking in digital communities to factors like power and status, it’s better to interpret their (non) participation in terms of competing discourses functioning within the group, which contribute in shaping participants’ identities and, respectively, affecting level and quality of interaction within the community. In the case of Dialogos we study a digital community that has been operating for three years and consisted of twenty-six teacher-members. Its aim was to function as an environment for professional development towards innovation in teaching practices in the school-subject of AGL-L, within the context of Greek secondary education reformation. This means that community participants experienced a transitional phase, as well as pressure, because of the fact that many entered a procedure of pedagogic identities reconstruction. Within the Dialogos e‑community there was a “struggle” between conflicting pedagogic discourses in the arena of AGL-L teaching reformation, which, according to Bernstein (2000), caused teachers’ pedagogic identities re-shaping, because of the institutional demands for change, which brought about identity work performed discursively and depicted through the quality of mutual engagement. Research on language teacher identity during the last decade informs us that in the case of educational reforms, teacher identity is rather fragile and unstable in an effort to espouse a model of schooling based on “new” pedagogy (Clarke, 2009). Dialogos’ teachers had entered a process to select, negotiate, reject, or accept parts of the dominant discourse within the community, which affected members’ connectivity to the group.

It is well known that teachers belong to several communities at the same time (real and/or virtual), as well as that teacher identity is constructed in relation to a process of negotiating with dominant and/or subordinate meanings in circulation within communities (teachers’ unions, professional / scientific associations, school boards etc.). Although community’s members share common meanings, practices, narratives, rituals etc., it is rather usual that they – at the same time – enact identities which draw from competing and opposing discourses functioning in the community. As a result, teachers usually live with competing identities while Sfard and Prusak (2005) categorize these competing identities as designated identity, which is ascribed by the institution/community, and actual identity, which is generally derived from personal practice. Teachers need to reconstruct their identity to cope with new challenges in the workplace, while this process is very complex and involves institutional construction and personal reconstruction of identities (Liu & Xu, 2011).

Wenger’s notion about communities of practice focuses on meaning negotiation and changes brought about, mainly through practice (Wenger, 1998). Nevertheless, as it will be apparent in this study, homogeneity in members’ views is not achieved totally through doing things together; it is also rather difficult to orient themselves, reflect on their situation and explore possibilities, merely by mutual engagement in shared practice. In a community of practice, each member carries and (re)shapes a unique personal identity, and this very fact affects his/her social behaviour within the group, and more specifically the degree and quality of interaction with other members. At this point Bourdieu’s concept of habitus (Bourdieu, 1990) is very useful to understand the way that networking and interaction is connected with teachers’ pedagogic identities. Bourdieu’s concept of habitus consists of modes of thought that are unconsciously acquired, resistant to change, and transferable between different contexts (Mutch, 2003). Accordingly, conflicting predispositions about several pedagogic perspectives, such as school-subject culture, teaching practices, pedagogic reformation, that constitute the setting for pedagogic identities enactment, affect many aspects of community life, and most of all networking and development of collaboration among participants.

The author of this paper held the role of the e-moderator in the Dialogos digital community and noticed several cases of teacher-members that, against all expectations, remained at the periphery of the group with little or no interaction with mentors and peers, enacting a fixed identity steadily embedded in specific pedagogic discourses. To a large extent the reason of insufficient interconnection, has to do with the fact that members’ enacted identities imbued by discourses not in compliance with those that the community mentors espoused. In the context of the above considerations, in this paper we study networking and interaction of teachers participating in digital communities. More specifically, we will deal with the pedagogic identities of a female participant teacher (T21) in Dialogos, who intersected with a variety of pedagogical and didactic discourses and ideologies that were in circulation and negotiation within the community, which greatly influenced the degree and nature of her networking in it.

Digital communities as a context for teaching practices reformation

During the last two decades in the context of Greek school education system, dominant ideologies about raising quality standards and reformation of teaching practices, alleges the use of digital media as the most appropriate tool for the vision of educational change and renovation. In the similar vein, digital communities of practice, as environments for teachers’ professional development are considered as having great advantage (compared to one shot seminars) because they can greatly increase membership and access to common resources, information and knowledge (Hung & Chen, 2001). Environments for networked teacher development (e.g. Moodle, BSCW, Blackboard, WebCT, Eluminate, etc.), with their individual interactive units (e-mail, e‑mail lists, exchange of text messages, resource repositories, forums or videoconferencing tools), offer opportunities for collaborative teaching and learning and sharing of learning resources and, above all, they exploit the most modern views on professional development through digital media (Riel & Polin, 2004).

Participant teachers in Dialogos, through a process of rich interaction, had initially designed and then applied technology-focused teaching material (lesson plans mainly) to their classes in the school subject of AGL– L. Dialogos designers implemented the logic of affinity space (Gee, 2005) and digital habitat (Wenger, White, & Smith, 2009). Affinity spaces – according to Gee – are actual or virtual environments in which the collaborating team of people participate in a multifaceted and dynamic way, utilizing social interactive services and recourses, offered by generators through one or more portals. Digital habitat is an online environment that provides the feeling of a real and not virtual collaborative site. Participants are willing to offer varied content, which they co-create and they are connected through fluid locality, while learning is constructed and distributed all over within the affinity space. Besides, the design and study of the e-community was based on the premise that learning takes place in social contexts (Ferguson, Gillen, Peachey, & Twining, 2013), in a process that it forms and is formed through discourses (Gee, 2010), and that participants’ identity re-constructions are situated mostly in socio-cultural, institutional and historical contexts (Wertsch, 1991; p.8).

Talking about teachers’ professional development and reformation of teaching practices, discussion has to do not only with technical issues but mainly with the pedagogical and other discourses that imbue teachers’ identities. Especially in the case of the school subject of AGL‑L in the context of Greek secondary education, some points have to be highlighted because of their significance in teachers’ identity (re)construction.

The most important part of the AGL-L sub-culture that irrigates teachers’ practices, has to do with the alleged unity and un-ruptured continuity of both the Ancient and Modern Greek language, which is a source of Greek national pride. Besides, within the Greek society the view that if students learn ancient Greek grammar, syntax and vocabulary, they will be sufficient users of modern Greek language, is quite common, since, despite words’ meaning changes taken place over the centuries, the two forms of Greek language are identical (Mackridge, 2009; p.300). Aspects of AGL‑L teaching involved with the “language question” (Van Dyck, 2008), while the one side support that Classical texts have to be taught in demotic translation, and the other that consider language (meaning particularly the Greek language) as a “value” and “lament” for a decline in linguistic “quality” in Greece. It is indicative also that many Greeks – academics, politicians, educationalists etc. – claim that this “language decline” is due to the abolition of Ancient Greek lessons at the lower secondary education. As a result, there is a considerable dispute in the Greek society – not only between linguists – concerning the necessity of the reintroduction of the ancient Greek language as a compulsory school-subject, since only by studying the classical texts at the original form, students can understand the “roots” of Modern Greek and realize, through etymology, the “correct” and “true” meanings of Modern Greek words (Mackridge, 2009; pp.325-26).

The above described sub-culture for the school subject of the AGL-L permeates, to a grate extend, the pedagogic identity and practices of the Greek teacher who teaches this subject. The so-called “classical philologist” teacher within the Greek secondary schools enjoys a high status, as s/he is believed that contributes to the perpetuation of the “sacred” keystone of the Greek national pride and ensures modern Greece’s central place among the western world. In this sense, the pedagogical mechanism (Bernstein, 2000; p.114), that structures and organizes, through the process of re-contextualization, the school subject of AGL-L, suppresses problematization and denaturalization of the dominant teaching practices.

Another aspect of the “language issue” that has to do both with the digital media and the teaching of AGL-L, was the appearance of the Greeklish phenomenon. Greeklish or Latin-alphabet Greek – that is, the representation of the Greek language with the Latin script – has been a feature of the Greek-speaking internet from the start. Greeklish became widely known in the 1990s (Androutsopoulos, 2000). The importance attributed to this phenomenon is evident from the fact that the Academy of Athens in 2011 issued a proclamation in which Greeklish was officially considered as a major danger to the survival of the Greek language. The Greeklish issue caused heated social and political debates as Greek graphemic system is considered inseparable from Greek language and intertwined with Greek national identity (Koutsogiannis & Mitsikopoulou, 2003).

Methodological points

I choose to study teacher’s T21 involvement and networking in the digital community, because I believe that she represents an interesting case that would shed light on the way in which teachers participate in digital communities. She is a highly qualified teacher (PhD candidate in classical literature) with a master’s degree in the same area. Besides, she has adequate digital literacy skills in teaching and participated in a number of training programs aimed at promoting and renewing teaching of her school-subjects. Thus, it was expected that the particular teacher would have a high level of networking and would be actively involved in the digital community, since at the time that she entered the group, she had a high level of experience and expertise. Most of all, it was expected that she would have enough power in the negotiation of meanings which were circulating within the community (Barton & Tusting, 2005).

In order to study T21’s social interaction within the community, I chose the case study methodology, because it enables focusing on one single person (Yin, 2002), while allowing the use of a variety of techniques to carry out the study in the natural environment of the person being studied. I followed the type of single-case design, since I was interested in T21 as a person who is placed in a digital community, which constitutes a context where pedagogic discourses irrigate pedagogic identities and, consequently, form social interaction. My methodological framework combines a mixed pattern of both qualitative and quantitative perspective, because I believe that in the case of studying connectivity and social interactions of a teacher community member, research is more fruitful when both the major research methods are utilized (Brannen, 2017).

The main purpose of the research in question was to try to determine (a) the extent to which T21 has been interconnected to the rest of the community-members (b) how and to what extent pedagogic identities enacted by T21, determine her social presence in the community. To get answers on the above research questions, I chose the methodological framework of ethnography, especially in the form of participant observation. As I have mentioned above, the role of the moderator gave me the opportunity to be “present” and have full experience of what happened within the e-community, both in the level of group and individuals. During my three-year immersion in the community’s life, I have been able to establish rich and comfortable social interaction, gaining teacher-members’ acceptance (Taylor, Bogdan, & DeVault, 2015). Besides – with the role of the person who supports the community’s digital platform, I had access to the discussions that took place in the electronic environment, so that I could elicit every useful verbal data in its written form.

At a first stage T21’s networking in the community was studied on the basis of the analysis of social networks (with the help of the UCINET 17 software – https://sites.google.com/site/ucinetsoftware/home) and reports from the Moodle environment (which was the platform for the digital community) aiming to study the social relationships she developed within the community. Based on the quantitative data (from UCINET and Moodle) our goal was to gain a full picture of her networking (through the analysis of the social network and her presence in the digital community). Then, exploiting data from interviews and posts, we aimed to shed light at the ways in which her professional identity as a teacher of Ancient Greek Language and Literature permeates and imbues the degree and nature of her community presence and networking.

With the help of social network analysis software, we focused on the following visualizations: (a) the average of the links that T21 has developed with other community members (mean), (b) the degree in which she is central / significant member in the group (coreness), (c) if she belongs in the core or the periphery of the community (d) her ability to transmit information to all other nodes on the network / how important T21 is within a network / How much she/T21 can be influenced by other members and how much she influences other members (closeness centrality) (e) visualization of her networked place in the social network.

Subsequently I analysed many qualitative data which I elicit from:

- Semi-structured interview given by the T21 teacher to the researcher as well as questionnaires she completed, before her participation in the online community.

- Data about her participation in the community, mainly through the collection of her online forum posts.

- Semi-structured interview given by the T21 teacher to the researcher after the completion of the online community.

With these interviews (duration 40’-50’), I asked T21 to construct narratives about her personal meaning that ascribes to the AGL-L school subject, her teaching practices, how she interprets the official attempts for the renewal of AGL-L, what her relationships were with other members within the community etc. In doing so, I sought to identify discourses she was already “embedded in” with regard to teaching, as well as to see whether her pedagogic identities affected her life and interconnection within the community. I then went through the process of classifying the data into autonomous and robust thematic categories in line with my research questions. The theoretical framework for the verbal data analysis belongs in the qualitative research paradigm, which is based on the blending of methodological patterns deriving from a wider social semiotics perspective as well as from different versions of discourse analysis (Ivanič, 2004).

Teacher’s T21 community presence and networking

Throughout the digital environment function, T21 entered the Dialogos community at an average of 52.6 times per month (she is ranked 14th in the total of 26 participants) and posted her thoughts to the various forums of the community at an average of 6.1 times per month (holding the 11th place).

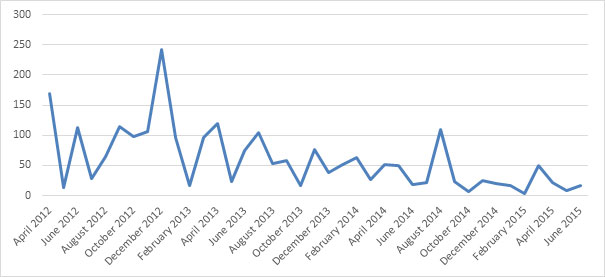

Figure 1. Frequency of teacher’s T21 entries in the community

The above graph that visualizes her presence in the digital community, shows that teacher T21 entered the online environment to read other members’ and publish or post her own messages at a varying pace (periods of frequent visits alternate with periods of diligent visits). After an initial period of very intensive presence, she kept relatively stable on average for the remainder period of her participation. In general, more intense activity is observed during periods when the teacher had to deliver teaching material or when her duties at school weren’t so heavy, thus allowing her to visit the platform and contribute with annotations to other members’ posts.

Interconnection index (Mean) of the teacher T21 with the other members of the AGL‑L community is 0,269 (she occupies the seventh place in the total of twenty-six members), meaning it was interconnected, discussed and related to the majority of the members of the community. If we analyse further the type of interconnection, we will find that the out-grade ratio is about 7.0 and rank her seventh in the total of twenty-six community members, while the index of the ties received by other members of the community (In Degree) are 6.0 and rank her tenth (in total of twenty-six). As far as it concerns teacher’s T21 place at the core / periphery of the community (coreness), she holds an index of 0,184, which means that she belongs to the core of the community, being a significant member as she occupies the eighth consecutive position (out of 26). Finally, her ability to receive or transmit information to and from other members of the network (closeness centrality) was estimated at 0.542 (how much she could be affected) and 0.464 (how much she could affect), with a maximum of 1,000.

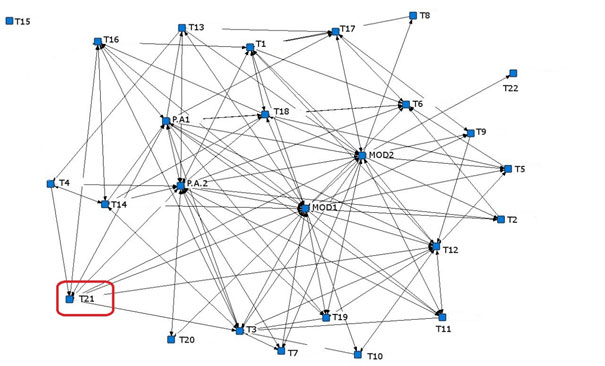

In the following graph there is a sociogram of the total social network that constituted the digital community of the AGL-Literature teachers. As it is depicted from the above data, teachers’ T21 networking was adequate, but in a lower degree than it was expected.

Figure 2. Visualization of teachers T21 place in the social network

Actual vs. designated identity and networking in the e-community

Before entering the e-community, teacher T21 enacts the identity of a teacher that “loves AGL‑L” and believes that this school-subject constitutes a high quality educational good and a “cultural treasure” which unfortunately is “at risk”. In her initial interview T21 states that she has chosen to participate in this program because of “her love for this school-subject, as this is what she studied and what she has been working on for years”. In addition, she argues that AGL-L is “rejected” and “challenged by a large number of younger teachers”, despite the fact that “they should try to reach its full potential”.

“[Ancient Greek school-subject] is what I studied and what I love most to teach … it’s a subject that I have been teaching for years and years. I think that it represents … a cultural treasure which we have undoubtedly rejected and, if anything, this is at least foolish … and - you know - this is what I want: as long as it depends on us [teachers] … to pass on this perception. And what worries me most is that … young children … OK … they stand with questioning against … the school subject of the Ancient Greek. What disturbs me most is that the questioning comes from my colleagues too and indeed from the special colleagues, that is, the philologists themselves. This is what is really bothering me.” (T21)

“I see …” (R)

“I do not see things that way. Nor do I see them stuck in the past and in a kind of a sterile love of antiquity. No! But, in any case, we can’t reject a treasure that all mankind tries to benefit from … in any case. Well, somehow, we are obliged to feel the need to take advantage of it.” (T21)

Interview, March 2012

It is clear that T21 embraces a culture concerning AGL-L that constructs a “sacred” image about the specific school-subject, which is also at risk from those who had the sublime task to protect it and maintain it unaltered in time: the younger philologists. T21 narratives about her life as a teacher, reflects the hegemonic ideology in the Greek educational context, about real or imagined enemies who threaten the core of the Greek language which, as mentioned above, has lexical, grammatical and syntactic continuity and match with its ancient form (Mackridge, 2009). As a result, a large number of philologists and many educational associations, oppose vigorously and fight every official attempt for reformations and changes, since they believe that the way that Ancient Greek is taught has to be retained as it was taught during the previous decades.

Teachers’ T21 identity constructions are imbued with the ideology that involves, on one hand perceptions about threats against the sacred role of the AGL-L school-subject, and, on the other hand, makes a direct connection between the Ancient Greek with the Modern Greek language and the dangers against language as a “value” which is caused because of the onslaught of the digital media. Drawing from her narratives we see that she is particularly acute in the Greeklish phenomenon, and even claims that she partly deals with the pedagogical use of digital media as a strategy, in order to make more effective shocks against the tendency of children to use them in written digital texts.

“... I think that the only way to oppose to the Greeklish whirlwind is to make full use of the new technologies in schools. Children have to learn to type in Greek, and they will do so, using the computer for school use … and you know something … at the beginning of the school-year … I asked my students in what type of keyboard [Greek or English] do they type their messages on facebook? Can you believe it? Not one kid responded to me that they wrote with Greek characters. Everyone … of course, in Greeklish.” (T21)

Interview, March 2012

Teacher’s Τ21 choice to engage with the digital community is an integral component of her professional identity construction as a teacher of AGL-L with a serious concern about the Greeklish threat, against the pure form of the Greek written language. Nevertheless, an interesting contradiction is detected within the content of her interview: on one hand – when enacting an identity of the classical philologist – she expresses her intense concerns and fears about her school-subject and the written form of Greek language that is threatened by the “new communication order” (Snyder, 2001). On the other hand, she legitimizes and justifies her engagement with the digital tools, through the need to use them in a way that defuses the threats that they cause against the “sacred” elements of her school-subject.

It is clear that teacher’s T21 identity and “sense of who am I” at the moment of her entrance in the digital community, draws on a traditional pedagogical discourse about the school subject of AGL-L and that she espouses the dominant subject’s culture in the Greek context. Nevertheless, the goal of the e-community function was to design teaching material (lesson plans), instilled by a new approach that would creatively transform the teaching of AGL-L. The main principles of this approach were (a) prioritizing knowledge about the ancient world and Greek antiquity instead of knowledge of the ancient Greek language, (b) teaching in a more creative way that would connect the ancient Greek past with the present, thus making students able to make critical arguments on the modern world’s problems, and (c) exploiting the logic of interdisciplinarity and multi-literacies as well as that of digital media.

Community members’ task within the e-community was to collaborate in design and construction of teaching material, which would be embedded in the philosophy described above. Teacher T21 was constantly present in the community designing and constructing her own material, as well as commenting and supporting her colleagues to do so. Nevertheless, her activity remained to an average, as she didn’t perform an identity of a fully interactive or much interconnected member and never change her position moving closer to the centre of the community (Lave & Wenger, 1991).

At the moment she joined the community, teacher T21 had a unique habitus (habitus is produced from “[t]he conditioning associated with a particular class of conditions of existence” (Bourdieu, 1990; p.53)), influenced by her immersion in her department’s (philologist) dominant culture. She espoused different subject-culture, compared to the dominant within the community, and held certain views about the nature of the AGL-L school-subject, teaching material, practices etc. New messages in the digital community though, attempted to instil dispositions not already present in her habitus, constituting an opposition between the actual and the designated identity (Sfard & Prusak, 2005). Despite the fact that according to (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990) “imposition of a cultural arbitrary” (pedagogic action) is often resisted, teacher T21, within the community fora kept a rather quiescent and consensual stance, while her lesson plans were harmonized to the community’s dominant views about AGL-L teaching.

Trying to find out if this kind of her involvement in the community (networking at an average degree and compliance with the dominant pedagogic discourse) stems from identity re-construction and/or habitus displacement, we make use of her narratives after the completion of the community function:

“Remembering this experience after all this time, I think that the most important of all was to find out exactly what ... what was the challenge for me as a teacher ... Designing a lesson plan that focuses in the knowledge of antiquity does not differ much from designing a lesson plan focusing in History. The REAL challenge was to make lesson plans for Ancient Greek that focuses on [ancient] language, and simultaneously escapes the logic of Hot Potatoes …” (T21)

“Did you get that?” (R)

“… not really … but some of my lesson plans had very good ideas.” (T1)

Interview, September 2015

Teacher T21 didn’t make any appreciable identity shift, inasmuch as she still embraces the same subject-culture about AGL-L, as before she got involved in the community. Her compliance with the dominant pedagogic discourse within the group, as well as the moderate networking and interaction degree with her colleagues, can be construed as a facet of her position as a “weak” subject (De Certeau, 1998). Weak subjects use tactics and manipulations, because they have not enough power to use strategies, so that they could re-organize state and order of things, the way that coincides with their interests.

During the three years of teacher T21’s involvement in the digital community, she intersects simultaneously with multiple modes of thought about the domain of interest (design learning activities and lesson plans aiming to renovate the AGL-L school subject). Her actual identity confronted with the ambiguities of participating in new and different professional settings and discourses, which were reflected on the way she interacted and engaged in the community’s life.

As an epilogue

Unlike Wenger’s aspect that identity changes are brought about in a smooth way through practice, the case of teacher T21, indicates that identity reconstruction within teachers’ digital communities is resistant to change, while many times conformity and docility may conceal misunderstandings and disagreements. A main factor that acts upon diminished members’ interconnection and lack of vivid meaning negotiation about the domain of the community, is the fact that teachers – taking the position of “weak subjects” (De Certeau, 1998) – avoid to come in open conflict with the representatives of the dominant discourse and culture within the community.

Although the culture of Greek philologists is gradually being characterized as more open and tolerant – due to the competition between “modern” and “traditional” pedagogic discourses – in many cases teaching of their school-subjects is a value-laden task, which runs the risk of becoming moral indoctrination (Frydaki & Mamoura, 2008). Many of the Dialogos digital community members endorsed such a subject-culture about AGL-L, that made them see their online community life as something extrinsic to their “offline” life and meanings that espouse within the multiple contexts outside the project (Howard & McKeown, 2011). T21’s involvement in the digital community, reverberates vividly the fact that teacher-identity seems to a deck of cards that “might be turned up at any time, depending upon the who, what, and where of circumstance” (Rodgers & Scott, 2008).

Based on the T21’s case “teacher’s self” seems like an “ensemble” of stories performed in different social contexts (Holstein & Gubrium, 2000). This means that s/he enacts fluid and fragile identities that have been constructed in the context of her/his professional and other experiences, prior to participating in online communities but also evolving in relation to real situations, practices and available resources (Connelly & Clandinin, 1999). Fluidity of identity construction implies that the participation of each teacher in an online community signals for her/his situations of intense competition between their “identity baggage” since in the process of constructing a personal identity “s/he walk(s) a tightrope in both developing a personal teacher identity which sits comfortably with their own sense of self and maintaining a balance between satisfying the requirements of state and society and providing the source and impetus for change” (Samuel & Stevens, 2000; p.478). Consequently, in their endeavour to comply with or to resist what is considered “appropriate” within a community of professional development or to reconcile contradictory identities (Kelchtermans, Ballet, & Piot, 2009), they are experiencing “emotional labour” (Zembylas, 2003) which is expected to be quite intense, since they are called upon to reconsider the way they see their teaching practices, their teaching subject and therefore themselves.

Experience of teachers’ participation and networking in the Dialogos online community, made clear that in many cases teachers do not consider online collaborating groups as an integral part of their role as a teacher, unless dominant pedagogic discourses and cultures within the community echoes school-subjects’ culture they espouse (Howard & McKeown, 2011). Digital communities’ designers and moderators should consider that participants’ interaction, is constructed within specific cultural frameworks (Wertsch, 1991; p.8). Apart from that, networking has to be positioned and understood in terms of discourses with which members meet in multiple contexts.

References

- Androutsopoulos, J. (2000). Λατινο-ελληνική ορθογραφία στο ηλεκτρονικό ταχυδρομείο: Χρήση και στάσεις [Latin-Greek orthography in electronic mails: Use and stances]. Studies in Greek Linguistics, 20, 75-86.

- Barton, D., & Tusting, K. (2005). Introduction. In D. Barton, & K. Tusting (Eds.), Beyond communities of practice: Language, power and social context (pp. 1-13). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bernstein, B. (1971). Class, Codes and Control. Volume 1: Theoretical Studies towards a Sociology of Language. London: Routledge.

- Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Blackler, F., & McDonald, S. (2000). Power, mastery and organizational learning. Journal of Management Studies, 36(4), pp. 833–851.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The Logic of Practice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture (Vol. 4). London: Sage Publications.

- Clarke, M. (2009). Language teacher identities: Co-constructing discourse and community. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Collins, A. (1991). Cognitive apprenticeship and instructional technology. In Educational values and cognitive instruction: Implications for reform (pp. 121-138).

- Connelly, F., & Clandinin, D. (1999). Shaping a professional identity: Stories of education practice. London: Althouse Press.

- De Certeau, M. (1998). The Practice of Everyday Life: Living and cooking. Volume 2 (Vol. 2). University of Minnesota Press.

- Van Dyck, K. (2008). The Language Question and the Diaspora. In R. &. Beaton (Ed.), The Making of Modern Greece: Nationalism, Romanticism, and the Uses of the Past (1797-1896) (pp. 189-198). Ashgate Publishing.

- Ferguson, R., Gillen, J., Peachey, A., & Twining, P. (2013). The strength of cohesive ties: Discursive construction of an online learning community. In M. Childs, & A. Peachey (Eds.), Understanding learning in virtual worlds (pp. 83–100). London: Springer.

- Frydaki, E., & Mamoura, M. (2008). Exploring teachers’ value orientations in literature and history secondary classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 1487–1501.

- Gee, J. (2005). Semiotic social spaces and affinity spaces. In D. Barton, & K. Tusting (Eds.), Beyond communities of practice language power and social context (pp. 214-232). Cambridge University Press.

- Gee, J. (2010). How to do discourse analysis: A toolkit. Routledge.

- Gherardi, S., Nicolini, D., & Odella, F. (1998). Towards a social understanding of how people learn in organizations. Management Learning, 29(3), 273–298.

- Grossman, P., & Stodolsky, S. (1995). Content as context: The role of school subjects in secondary school teaching. Educational Researcher, 24(8), 5-23.

- Gudmundsdottir, S. (1990). Values in pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Teacher Education, 41(3), 44-52.

- Holstein, J., & Gubrium, J. (2000). The Self We Live By: Narrative Identity in a Postmodern World. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Howard, S., & McKeown, J. (2011). Online practice & offline roles: A cultural view of teachers’ low engagement in online communities.

- Hung, D., & Chen, D. (2001). Situated cognition, Vygotskian thought and learning from the communities of practice perspective: Implications for the design of web-based e-learning. Education Media International, 38(1), 3–12.

- Ivanič, R. (2004). Discourses of writing and learning to write. Language & Education, 18(3), 220–245.

- Jørgensen, M., & Phillips, L. (2002). Discourse analysis as theory and method. Sage.

- Kelchtermans, G., Ballet, K., & Piot, L. (2009). Surviving diversity in times of performativity: Understanding teachers’ emotional experience of change. In P. Schutz, & M. Zembylas (Eds.), Advances in teacher emotion research: The impact on teachers’ lives (pp. 215-232). London: Springer Publishing.

- Koutsogiannis, D., & Mitsikopoulou, B. (2003). Greeklish and Greekness: Trends and discourses of “glocalness”. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 9(1).

- Laclau, E., & Mouffe, C. (2001). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical democratic politics. Verso.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Liu, Y., & Xu, Y. (2011). Inclusion or exclusion? A narrative inquiry of a language teacher’s identity experience in the ‘new work order’ of competing pedagogies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(3), 589-597.

- Mackridge, P. (2009). Language and national identity in Greece, 1766-1976. Oxford University Press.

- McLoughlin, C., Brady, J., Lee, M., & Russell, R. (2007). Peer-to-peer: An e-mentoring approach to developing community, mutual engagement and professional identity for pre-service teachers. Paper presented at the Australian Association for Research in Education Conference. Freemantle, Australia.

- Mutch, A. (2003). Communities of practice and habitus: a critique. Organization Studies, 24(3), 383–401.

- Najafi, H., & Clarke, A. (2008). Web-Supported Communities for Teacher Professional Development: Five Cautions. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 8(3), 244-263.

- Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (1999). Building Learning Communities in Cyberspace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, a Wiley Company.

- Ribeiro, R., Kimble, D., & Cairns, P. (2010). Quantum phenomena in Communities of Practice. International Journal of Information Management, 30(1), 21-27.

- Riel, M., & Polin, L. (2004). Online learning communities: Common ground and critical differences in designing technical environments. In S. Barab, R. Kling, & J. Gray (Eds.), Designing for virtual communities in the service of learning (pp. 16–50). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Rodgers, C., & Scott, K. (2008). The development of the personal self and professional identity in learning to teach. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman Nemser, & D. McIntyre (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions in changing contexts (3rd ed. pp. 732-755). New York: Routledge.

- Samuel, M., & Stevens, D. (2000). Critical dialogues with self: developing teacher identities and roles - a case study of South African student teachers. International Journal of Educational Research, 33(5), 475-491.

- Sfard, A., & Prusak, A. (2005). Telling identities: In search of an analytic tool for investigating learning as a culturally shaped activity. Educational Researcher, 34(4), 14-22.

- Smyth, Κ., & Bruce, S. (2012). Employing the 3E framework to underpin institutional practice in the active use of technology. Educational Developments, 13(1), 17–21.

- Snyder, I. (2001). A new communication order: Researching literacy practices in the network society. Language and Education, 15(2-3), 117-131.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice. Cambridge University Press, UK.

- Wenger, E., White, N., & Smith, J. (2009). Digital habitats: Stewarding technology for communities. CPsquare.

- Wertsch, J. (1991). Voices of the mind: A sociocultural approach to mediated action. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Yanow, D. (2004). Translating local knowledge at organizational peripheries. British Journal of Management, 15(S9–25).

- Zembylas, M. (2003). Interrogating “teacher identity”: emotion,

resistance, and self-formation. Educational Theory, 53(1), 107-127.