Emergent Evaluation: An initial Exploration of a Formative Framework for Evaluating Distance Learning Modules

Palitha Edirisingha [pe27@le.ac.uk], Phil Wood [pbw2@le.ac.uk], University of Leicester, School of Education, No. 21, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RF, United Kingdom [http://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/education]

Abstract

Evaluation of student learning is becoming ever more important in higher education, partly because of increasingly performative structures within universities, and partly as the result of a developing interest in rolling development of curricula and teaching resources. Historically, for both face-to-face provision and distance learning, such evaluation has generally been captured by end-of-module questionnaires. Whilst these evaluative media may capture some reflections of student learning, they are often poorly focused, and rely wholly on summative perspectives which are captured at a point remote to the learning process itself. The current paper reports on an initial investigation centring on developing a formative framework for evaluating distance learning modules. It is distinguished from typical summative questionnaire evaluations by the collection of “live” feedback from students as they undertake a module, allowing for insight and feedforward to develop materials as students undertake the module. This is achieved by using a modified version of an approach called Lesson Study, a collaborative planning and evaluation tool which originated in Japan (Lewis et al., 2009).

Keywords: Lesson study, Course Evaluation, Distance Learning, E-learning, Action Research.

Developing an approach to evaluation of distance learning

The evaluation of modules in higher education is an important driver for change and curriculum development. The standard tool used in evaluating student experience is the summative questionnaire which students are asked to complete at the conclusion of a module. These questionnaires often cover a spectrum of issues including reflections on activities, tutoring, resources, and environments, but rarely cover student learning. The statements are often general in nature, e.g. “what was the quality of learning resources?” which lead to over-simplified responses which cannot pick up the nuance of experiences. As such, there are several issues with the accuracy and utility of summative questionnaires. Firstly, many students, especially on distance learning courses, do not bother to fill in the questionnaires, either because they are busy professionals, or because they are happy with their experiences so do not value the opportunity to share their views. Secondly, questionnaires are inherently retrospective, which leads to over-simplification of views, and leads to future developments being undertaken after the students have finished their learning. Finally, the analysis of questionnaire data is often reductive, leading to numeric summaries, with little explanatory or discursive insight into the complexities of the activities undertaken.

These restrictions are recognised within the literature already (Wachtel, 1998) and have led to the development of alternative approaches to gain a better evaluation of learning, whilst also developing the curriculum. For example, Ellery (2006) developed a multidimensional evaluation framework for use on a campus-based course on data analysis in social science research methods. The approach not only gathered information from students, but also captured lecturer perspectives to create a more complete picture of student experience and learning. Several methods were used to capture evaluative data that were then used to inform curriculum and pedagogic development. Benson et al. (2009) extended the idea of formative evaluation further by developing a participatory evaluation model, that again was multi-modal, based on the work of Jackson and Kassam:

“a process of self-assessment, collective knowledge production, and cooperative action in which the stakeholders in a development intervention participate substantively in the identification of the evaluation issues, the design of the evaluation, the collection and analysis of the data, and the action taken as a result of the evaluation findings.” (1998; p.3)

Here, students were involved in identifying the terms of evaluation before being involved in data capture and interpretation. This made them and lecturers joint investigators into their own work, and gave a sense of joint responsibility for improving modules and learning. However, in both cases, these alternative approaches were developed within campus-based contexts. In this investigation, we attempted to develop a model which could be used in distance-learning contexts.

Aims of the pilot study

This investigation was undertaken on a distance-learning MA in International Education course. The programme includes a 30 credit module on research methods, the second module of four which make up the first 120 credits of the masters course. We decided to focus on this module as it has been identified as one which students struggle with and which often leaves them with poor and incomplete understanding. In developing an evaluative process, we wanted to create an approach which allowed for:

- diagnostic and formative module evaluation;

- a clear link to curriculum development;

- a framework for distance learning review which is more than a performative activity;

- putting pedagogy (interpenetration of teaching, learning, curriculum and assessment and their interaction with teachers and students) at the centre of the process;

- emergence and trialling of new approaches as a standard element of our work.

Outlining the evaluative framework and pilot data collection

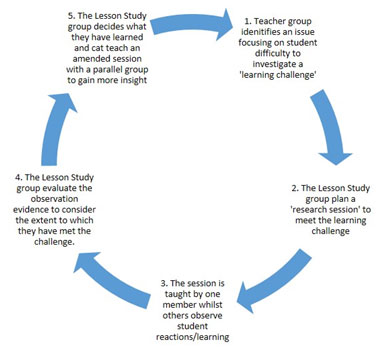

To develop a formative approach to module evaluation, we decided to attempt to use a variant of lesson study (Lewis et al., 2009), a framework which attempts to help teachers improve their pedagogy by working collaboratively to improve student learning. Lesson study has been a core feature of educational development in Japan for over 100 years. Since the end of the 20th century that it has moved beyond Japan, and is now a well-established method for pedagogic development in countries around the world. It is a collaborative form of action research (Wood et al., 2015), which cannot be undertaken by individual tutors. A basic cycle of lesson study is given in Figure 1, and begins with a group (as few as two will work) of teachers coming together to identify a learning challenge. The learning challenge is a specific element of learning that students struggle with, and often fail to understand well. Having identified such a challenge, the group then work together to plan a lesson which engages with the elements of that challenge to create a pedagogic experience which will help students gain a greater level of understanding. This requires the teacher group to spend time considering not only the teaching element of the lesson, but also the learning of the students. How will they engage with and make sense of the subject matter? How will particular activities be understood and completed?

Once the lesson is planned and resourced, one member of the group teaches the lesson, whilst the other members observe a number of students. The observations focus on trying to note how students react and make sense of the lesson material. Once the lesson has finished, the teacher group reconvenes to consider the evidence for student learning and the degree to which the lesson has helped them move forward in their understanding. If there is the opportunity, a second lesson can be taught again to a parallel group, making amendments to the original lesson where necessary, to maximise the level of pedagogic insight gained from the process.

Figure 1. A basic lesson study cycle

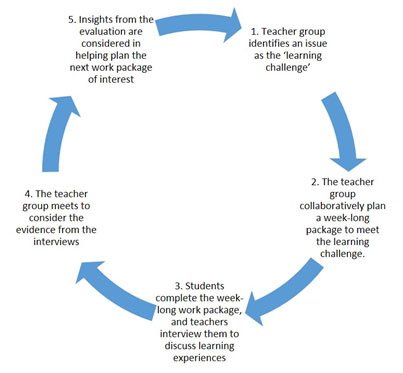

To date, lesson study has only been applied in face-to-face contexts, in large part due to the school-based context within which the vast majority of lesson study takes place. We decided that we would develop a modified version of this approach as the basis for developing and evaluating student learning as it occurred within a distance learning module. Our research was undertaken with three students who were undertaking the research methods module, and did so using an amended version of the cycle in Figure 1. A central element of the lesson study approach is the observation of the research lesson, an activity which obviously does not translate directly to a distance learning context. However, where appropriate, the use of discussion board dialogue might stand in place of this element of the cycle. We decided to use individual semi-structured stimulated recall interviews (Lyle, 2003) as the main source of evidence for approaches to, and levels of, learning in place of observations, and hence the amended lesson study cycle looked like that given in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Modified lesson study cycle for distance learning contexts

This cycle was used to investigate two areas of the research methods module which often cause problems in student learning:

- developing research questions;

- organisation, analysis and interpretation of data.

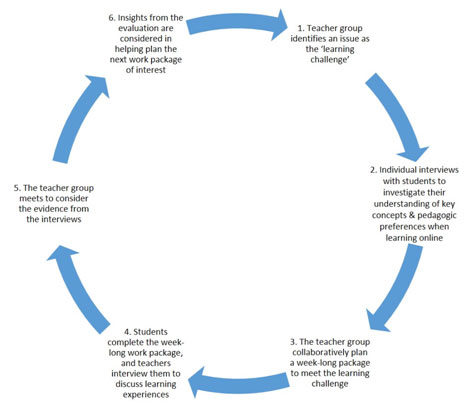

Having completed these two cycles of investigation, we decided to include an extra step in the process, based on research in lesson study at higher education level (Wood & Cajkler, 2016). In a final, third, cycle which focused on the development of critical writing in student work, we included a step before the first planning meeting which consisted of individual interviews with the three students to investigate their understanding of some of the key concepts of critical writing, and to ascertain the pedagogic approaches they preferred when learning online. This amended cycle is shown in Figure 3.

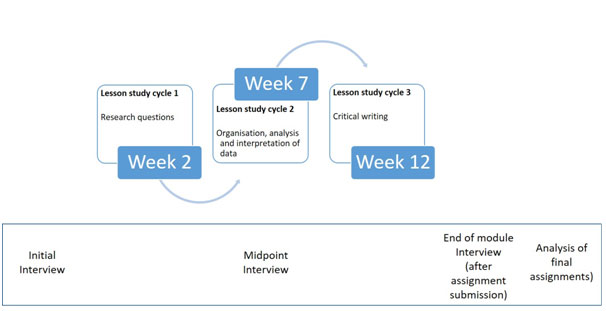

The module lasted for 16 weeks, with the three cycles of modified lesson study occurring at weeks 2, 7 and 12 (see Figure 4). In addition, general individual interviews were undertaken with the three students at the beginning, middle and end of the module, and the final assignments of the students were analysed. The intention of using this model was to help us to develop a deeper understanding of what students believed they were learning, but also how they were making sense of the module materials. As such, this gave us an opportunity to evaluate, amend and develop approaches as the module unfolded (hence the idea of an emergent approach). The approach also allowed us to gain ideas and insights from each other as tutors as we developed the module together.

Figure 3. Enhanced modified lesson study cycle for distance learning contexts

Figure 4. Overall schematic of data collection for emergent evaluation approach

Initial Results

This pilot study allowed us to gain a number of insights. Here, we focus on the reflections and advantages we gained as curriculum developers, and also consider some of the possible issues and challenges of scaling up the approach to larger groups.

At the beginning of the module, the initial interviews we completed gave us very useful insights into relevant prior learning of students. One student had completed a social research methods course at undergraduate level, and therefore felt that she had a relatively clear foundation on which to build her studies. Another student had come from a non-social sciences discipline, but had been involved professionally in small-scale research projects, so had some practical experiences of research involvement, but little theoretical perspective. This helped us understand the very different starting points from which students enter the module on research methods. The interviews also gave us opportunity to understand in some detail the learning practices students had developed in their first module, prior to research methods. Again, even though we only conducted interviews with three students, all had very different approaches to their studies, often based on prior learning approaches, but also practical, work-based constraints. By using the information from the initial interviews we were able to gain some critical and rich insights into prior learning and students’ approaches to their learning. These provided useful starting points for our collaborative planning sessions once the lesson study cycles started.

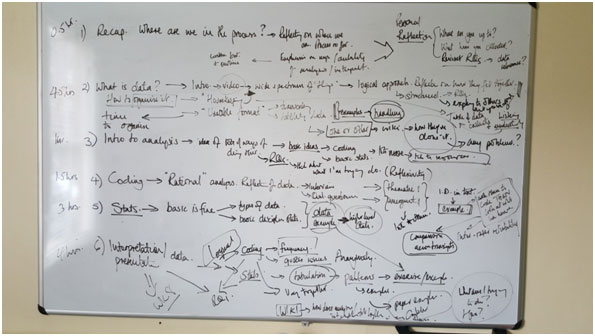

The first two modified lesson study cycles (see Figure 2) which focused on research questions and data organisation/analysis/interpretation, proved to be very positive experiences for the two researchers. The opportunity to discuss and build a week-long work package through discussion allowed us to develop a more critical and in-depth consideration of the content to be covered. During the second cycle, we were also able to use student stimulated recall data from the first cycle to inform our discussions. In the planning meetings we built out from some basic principles to create possible narratives and activities to create a coherent package for students. An example of board notes from the planning meeting for modified lesson study cycle 2 is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. An example of board notes from the planning meeting for lesson study cycle 2

In these meetings we considered how we thought the students would engage with the materials and how this would help them in understanding the issues and concepts covered during that week. These predictions were then considered again when we evaluated the week’s work package in the evaluation meeting, having interviewed students to understand their perception of their learning. As such, this approach gave us a lot of insight and further questions concerning the development of curriculum materials. As we evaluated one element of the work, it helped us consider the development of the next element, often in ways we had not envisaged, leading to the notion of an emergent process.

The emergent evaluation approach allowed us to develop elements of the curriculum in real time, driven by student response and reflection, thereby helping us shape the content and approach of the module. This meant that we gained a deeper understanding of the complexities of pedagogies, with the chance to respond to need. In this way the evaluation became both diagnostic and formative rather than summative as often happens in module evaluation.

In the final cycle of modified lesson study we attempted to consider how a participative model (Wood & Cajkler, 2016) would work (see Figure 3). On this occasion, we started by asking the students to explain particular pertinent concepts such as ‘critical writing’ to gauge their understanding of core concepts for the week-long work package on assignment writing. We then went on to ask them what they believed they would gain from most in the week given the focus on starting their assignments. These reflections were extremely useful in helping us understand what activities would have most potential impact in taking their learning forward, and some of their ideas and reflections were incorporated into our discussions and curriculum development.

Reflections and initial insights

Using a modified approach to lesson study as the basis for emergent evaluation has proved to be a very positive experience. It allows for rolling renewal and development of materials, and moves away from the overly-general summative evaluations which are often too vague to help develop new pedagogic approaches. We believe that an emergent approach can offer useful insights and allow for curriculum development which is both well-grounded in an understanding of student needs, and also which helps programme tutors gain a shared perspective concerning the course they are responsible for. We also believe that lesson study, in a modified form, translates well from a face-to-face setting to one which supports development of distance learning pedagogies.

There were inevitable challenges, the most important being time. The three cycles of lesson study led to intensive work, with interviews leading to planning and package design and development within one working week before student use. This means that time was not only being made to complete the lesson study cycle, but also to complete a work package within a five-day window. This was intensive work, but did rely on a foundation of pre-existing module material, so that package development was in some cases a process of editing and reorienting rather than starting from scratch. Because of the intensive work required to develop a work package, and the multiple cycles used across the module, we envisage an emergent evaluation approach being used in a targeted manner, perhaps across two modules per year. In this way, it could be used as an integral approach to renewing and innovating on distance learning courses. To attempt to use it on a larger number of modules over one academic year would, in our opinion, be unsustainable.

The cohort involved in this pilot was small, with only three students being involved in the interviews, and five overall in the cohort. There is a question mark as to how well this model would scale-up, but we see no reasons why it should not work with larger cohorts.

Finally, there is a wider question mark over the degree to which emergent evaluation would fit within wider, increasingly performative, evaluation frameworks used by universities. We see this approach as being used instead of summative evaluations for the simple reasons that it gives more nuanced, more critical and in-depth insight into the learning and needs of students. However, as such it is working with the complexities of pedagogy and students; the use of summative statistics would be drastically over-reductive in this context, but is often the type of data that university quality assurance systems need.

We see emergent evaluation as focusing on developing the quality and focus of curriculum approaches through diagnostic and formative debate with students and other colleagues. This pilot has demonstrated that a great deal can be gained by working collaboratively through a modified lesson study approach, supported by more general periodic interviewing. The constant, iterative approach allows for immediate incorporation of lessons learned and allows us to gain a much more in-depth understanding of student learning patterns and needs.

References

- Benson, R., Samarawickrema, G., & O’Connell, M. (2009). Participatory evaluation: implications for improving electronic learning and teaching approaches. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(6), 709-720.

- Ellery, K. (2006). Multi-dimensional evaluation for module improvement: a mathematics-based case study. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(1), 135-149.

- Jackson, E. T., & Kassam, Y. (1998). Knowledge shared: Participatory evaluation in development cooperation. West Harford, CT: Kumarian Press.

- Lewis, C. C., Perry, R. R., & Hurd, J. (2009). Improving mathematics instruction through lesson study: A theoretical model and North American case. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 12, 285-304.

- Lyle, J. (2003). Stimulated recall: a report on its use in naturalistic research. British Educational Research Journal, 29(6), 861-878.

- Wachtel, H. K. (1998). Student Evaluation of College Teaching Effectiveness: a brief review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 23(2), 191-212.

- Wood, P., & Cajkler, W. (2016). A participatory approach to Lesson Study in higher education. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, 5(1), 4-18.

- Wood, P., Fox, A., Norton, J., & Tas, M. (2015). The Experience of

Lesson Study in the UK. In L.L. Rowell, C. Bruce, J.M. Shosh, & M. Riel (Eds.), Palgrave International Handbook of Action Research (pp.203-220). London:

Palgrave Macmillan.