The Fragmentation Blog: Applying Constructionism to the Teaching of Literature

Luisa Bozzo [luisa.bozzo@unito.it], University of Torino, Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures and Modern Cultures, Via S. Ottavio 20, 10100 Torino, Italy [www.unito.it]

Abstract

Using Internet facilities to integrate constructionist activities in the English Literature syllabus makes the learning experience more effective in several ways. These activities entail a high degree of involvement of all students throughout the project, a heightened quality of the groups’ work and achievement, and a wide-range and long-lasting learning effect on all participants. The Fragmentation Blog is an instance of such effectiveness. Teachers guided a mixed-ability class of students in their last year of high school towards the production of a class blog on the theme of “fragmentation” in modern and contemporary English literature. The multi-disciplinary activity, making students co-operate in small groups to give a personal interpretation of their studies and to present their work outside the classroom, corresponds to Papert’s principles of constructionism, and has the features recommended by Herrington, Oliver and Reeves about “authentic learning”. The overall outcome was positively surprising and is encouraging enough to pursue the continuation and expansion of this kind of teaching practice.

Keywords: class blog, constructivism, constructionism, authentic learning, group work, teaching literature.

Introduction

In my ten-year experience as a teacher in the Italian Secondary School system, I have often observed that my colleagues’ practice is overwhelmingly based on instructional models. Though there is nothing wrong with it, I am convinced that integrating such models with constructionist-based activities may enrich and enhance the range of the students’ results. As is often noted, the main cognitive objectives of instructional models (knowledge, comprehension, application) are quite low in Bloom’s taxonomy and its revised versions (Bloom et al., 1956; Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001), as compared to the objectives activated by constructionism (analysis, synthesis, evaluation, creation). Therefore, supplementing instruction with construction in the syllabus entails the broadening of the cognitive objectives. After briefly introducing the basic theoretical foundations, this article presents and describes an instance of a constructionist-based activity, and discusses its results.

Constructivism, constructionism and authentic learning[1]

According to von Glasersfeld’s (1989) epistemological theory of radical constructivism,

1. knowledge is not passively received but

actively built up by the cognizing subject;

2. the function of cognition is adaptive and serves the organization of the

experiential world, not the discovery of ontological reality. (p.162)

In the constructivist perspective, knowledge is built on the basis of social and individual experience, through reflection, re-elaboration, and analysis of new experiences in the light of past ones. Thus, there is no such thing as “absolute” knowledge, but several differing perspectives may coexist, even in scientific disciplines. As a consequence, learning is seen, rather than an act of transmission of objective knowledge from teacher to learner, as an active process of acquisition of the propositions and of the strategies which are most apt for the achievement of one’s objectives; such process of acquisition is elaborated through a vast number of variables including dialogue, experience, and comparison with past experience.

The ideal features of a constructivist learning environment are: exposure to multiple perspectives; learner-centred approach; role of teacher as facilitator of the learning process rather than as instructor; cooperative activities which favour the social negotiation of meaning (Vygostky, 1978); opportunities to build one’s representation of knowledge; environment supportive of learners’ motivation and autonomous exploration.

Constructivism provides the basis for Papert’s pedagogical theory of constructionism, according to which “learning is most effective when part of an activity the learner experiences as constructing a meaningful product.” (1989, p.1).

Constructionist learning involves students drawing their own conclusions through creative experimentation and the making of social objects. The constructionist teacher takes on a mediational role rather than adopting an instructionist position. Teaching “at” students is replaced by assisting them to understand—and help one another to understand—problems in a hands-on way. (Wikipedia)

In Papert’s view, producing objects allows students to elaborate concepts and knowledge in various ways, while interacting effectively with their peers.

The theory of constructionism is supported and extended by Herrington, Oliver and Reeves, who advocate “authentic learning”. In their view, the activities which create authentic learning should have the following features:

Authentic activities have real world relevance, […] are ill-defined, requiring students to define the tasks and sub-tasks needed to complete the activity, […] comprise complex tasks to be investigated by students over a sustained period of time, […] provide the opportunity for students to examine the task from different perspectives, using a variety of resources, […] provide the opportunity to collaborate, […] provide the opportunity to reflect, […] can be integrated and applied across different subject areas and lead beyond domain specific outcomes, […] are seamlessly integrated with assessment, […] create polished products valuable in their own right rather than as preparation for something else, […] allow competing solutions and diversity of outcome. (2003, pp.60-61)

The blog

The tools of information technology provide an environment which is close to the ideal described in the previous paragraph. For instance, World Wide Web publishing facilities such as www.blogger.com allow anyone to publish their work on the net so that it is immediately and widely shareable and permanently available. For this reason, the proponents of the project established that the students prepare the final product of their work in an electronically publishable format.

The Project Fragmentation consists in the creation of a class blog containing the multimedia products of groups of students in their final year of high school. The multimedia products are the result of the class’s work over the whole school-year on the analysis of the theme of “fragmentation” throughout the British and American Literature of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.[2] The students were asked, as a final project, to give a personal interpretation of one or more of the topics analyzed in the course; they were given total freedom of expression both in terms of contents and form, provided their work was electronically storable as written text, images, sound and music, video, etc. The class blog, published online at the address http://5c2010projectfragmentation.blogspot.com, was eventually presented to the board of examiners of the school-leaving examinations.

The context

The project was carried out by the class English teacher, Ms L. Bozzo, and the class English mother-tongue consultant, Ms Kirsty Ramsbottom, with one class of twenty-two students from the Scuola Internazionale Europea Statale “Altiero Spinelli”[3] of Torino, Italy. The academic qualities, English language competence and overall study performance of the students were extremely heterogeneous, thus making the experimentation more challenging and interesting. Nine of the students were in the school’s foreign languages curriculum, and thirteen were in the science and math curriculum. Their English language proficiency level ranged from B1+ for the weakest to C2 for the best, according to the CEFR (2001) classification. Some students’ general commitment to class work and school activities was very high, whereas some others’ was bordering on dropping out.

The objectives[4]

The project has been devised with a configuration of objectives in mind, in compliance with the school’s curriculum and the subject’s syllabus.

First of all, the method, the level and the contents of the activity are such as to favour the motivation of all the students, the main goal being to interest and involve the whole class in a way that they may find the experience satisfying and self-empowering. The choice of an informal cooperative approach,[5] based on group work and peer teaching, aims at strengthening shared learning strategies, whereas the adoption of multimedia resources is meant to stimulate individual multiple intelligences,[6] by activating different cognitive styles;[7] formal assessment is kept to a minimum in order to neutralize students’ affective filter;[8] the expected result is improved academic performance and enhanced self-efficacy.[9]

The objectives concerning the syllabus are to reinforce the knowledge and understanding of the mainstream features of the Anglo-American literature and art of the twentieth century. The objectives concerning SLA[10] are: to develop the passive and active knowledge of the lexis pertaining to the chosen semantic areas, to improve one’s understanding of searched materials, and, most of all, to improve the ability to produce text and discourse in English to present one’s work in an engaging way.

The project also includes objectives about ICT competences such as manipulating images, sound and video from the Internet, creating presentations and videos with computer programs, publishing one’s materials online, using blogs. The expected outcome of working cooperatively is that students learn to negotiate on the contents and the tasks of their product, to compare and judge each other’s opinions, to contribute with their skills and competences to the carrying out of their work, to ask for help when they deem it necessary.

Finally, the project involves interdisciplinary and intercultural objectives. The former encourage students to develop the ability to research, select, create, assemble and present diverse materials such as text, music, images, and videos. The latter entail the understanding of the multi-faceted factors which contribute to the creation of the literature and culture of a definite age, in order to compare and contrast them with one’s own experience and time. The ultimate goal is to develop the students’ ability to comprehend the co-existence of different points of view in cultures, to provide them with some tools to discover and explore autonomously, and to acquire a critical, independent and ever-widening learning style.

The contents: a purposefully ill-defined task for competing solutions and diversity of outcome

As far as the contents of the final product are concerned, the students are free to choose the topic or topics which interested them most, provided they connect with the course’s syllabus (Ramsbottom, 2009). As Herrington, Oliver & Reeves (2003) state,

Problems inherent in the activities are ill-defined and open to multiple interpretations rather than easily solved by the application of existing algorithms. Learners must identify their own unique tasks and sub-tasks in order to complete the major task. (p.60)

A further reason for allowing a certain degree of freedom in the choice of the contents is the expectation that students refer to their rich, diverse cultural backgrounds and interests thus making their work more personal and therefore more meaningful.

The methods: a holistic perspective and a cooperative approach

The literature course leading to the final project uses a variety of teaching techniques, in a holistic perspective.[11] The project takes place at the end of the course, and is broadly based on the cooperative principles of positive interdependence, face-to-face interaction, individual responsibility, group monitoring and processing (Johnson & Johnson, 1999). In the project, students are asked to work in small groups; each group takes on responsibility for all the major decisions about membership, contents, forms, task assignment, timing, and self-evaluation. The heterogeneity of the class and of the groups is advantageous under several aspects, as Johnson, Johnson and Holubec (1994, p.154) underline, since diversity promotes the exchange of roles within the group, according to the varying degrees of competence in the various fields involved, and favours the exploration of new perspectives to perform the tasks. The roles of the teacher and the consultant shift from being the main sources of information and organizers of the activities to facilitating and monitoring the work in progress. Formal assessment is restricted to the very end of the project, and it is shared in the form of class discussion.

The organization: facilities, tools and project scheduling

Some stages of the project took place in the school’s premises – classroom and computer lab –, whereas the bulk of the work, that is the production of the blog posts, was left for the students to do at home.

The choice of the tools was mainly determined by thrift, since the project was unfunded. Therefore the tools were chosen among those available in the school’s lab and the freeware online. The hardware included personal computers with DSL Internet connection, projector, video camera, microphone, and scanner. The software included Windows Movie Maker, Microsoft PowerPoint, LEAWO Free PowerPoint to Video, VLC Media Player. The blog website was www.blogger.com.

The Project Fragmentation may be summed up in ten stages, which were carried out within the space of nine months, from September 2009 to May 2010, reaching its climax in April-May.

Stage 1: Planning

Early in September, the state teacher and the consultant prepared the project programme, on the basis of the students’ traits and needs, and in the light of previous years’ experiences. The elements which were taken into account were the national curriculum, time, the tools available, the textbook’s syllabus, the students’ and the teachers’ interests and competences. Immediately afterwards followed the selection, adaptation and/or creation of the materials. Kirsty Ramsbottom worked mainly on the contents, the materials and the methods of the course, while Luisa Bozzo worked on the planning and carrying out of the final project. The two teachers were in class and attended to the students’ progress throughout the course at all times.

Stage 2: Introduction of the project

At the beginning of the course, in mid-September, the final project was presented to the class with the aim of giving additional meaningfulness to the course, and students were encouraged to give their opinion, make suggestions, start collecting information and materials, and think about the type of product they would like to create. The students’ reaction was very positive from the very beginning.

Stage 3: Course Fragmentation

From September 2009 to April 2010, the students followed the course on the literature and art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.[12] The course dealt with the multi-faceted theme of “fragmentation”: the fragmentation of memory, of truth, of the self, of the perception of the world, etc. The didactic approach was purposefully varied: for instance, in some classes students created cubist pictures and wrote dada poems; in others they analyzed historical documents such as posters, photographs, videos and audio recordings; sometimes they listened to, analyzed and then performed songs. At regular times, teachers checked on the students’ preliminary research work on the preparation of their blog posts.

Stage 4: Project arrangements

In mid-April, one class was assigned to the project arrangements. Students were asked to fix the composition of their groups, the topic of their work, and the medium/media of their choice. Despite cooperative learning experts’ advice about the composition of groups,[13] teachers intentionally left students free to choose their group mates, on account of the fact that despite being academically heterogeneous the class was socially very cohesive; thus, students could group according to their topics of interest and to their home meetings agreements. The remainder of the lesson was spent on providing students with feedback and suggestions on their projects, and on establishing calendar and deadlines.

Stage 5: Projects realization at home

The most intense and productive part of the project was carried out autonomously by the groups, at home. Students worked for about ten-twenty hours each, and often resorted to the help and advice of experts on ICT such as relatives and friends; some also required their teacher’s guidance via e-mail and in person at school.

Stage 6: Projects realization at school

The first two classes in May took place in the school’s computer lab, featuring a pc per group and a pc and projector for the teachers. The activities included: collective creation of the blog’s cover page; sharing of the state-of-the-art of the groups’ work; group research of further materials on the Internet; group and class discussion of the contents and of technical difficulties; teacher feedback on each of the previous; teachers’ informal monitoring and assessment. At this stage, four of the students decided to split their group and go solo, because each had developed different ideas and wished to process them individually.

Stages 7 and 8: Projects implementation and publication

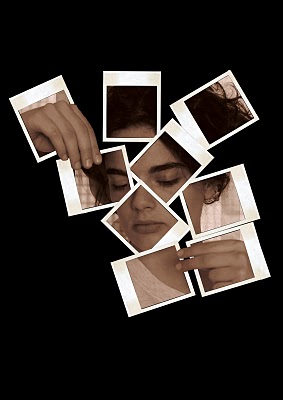

Students completed their project according to the feedback received in the lab sessions, and submitted it to the teachers for further advice and correction. Eventually, the posts were published in the blog.[14] Figure 1 and 2 provide two examples.

Figure 1. “Trying to Hold Myself

Together”

source: http://5c2010projectfragmentation.blogspot.hu/2010/06/fragmentation-by-eva.html

Figure 2. “Fragmentation”

source: http://5c2010projectfragmentation.blogspot.hu/2010/06/fragmentation-by-eva-luraschi.html

Stage 9: Project presentations

In the second half of May, in the school’s lab, each group presented their work to the class and teachers, explaining the reasons for their choices and the procedures they followed. Each presentation was followed by a class discussion on the quality of the work and by formal assessment by the teachers. This stage represented the acme of the activity, and most projects earned the appreciation and admiration of peers and teachers. The natural follow-up of the project was the students’ spontaneous dissemination of their experience among schoolmates, friends and family, to the point that other classes asked whether they could join in the project and blog. Unfortunately, their English teachers declined, making excuses about lack of time and of ICT competences.

Stage 10: Blog presentation at the final exams

In June, the board of examiners was shown the blog as a proof of the class’s global preparedness. They commented very positively and expressed interest in the methodology.

Monitoring and Assessment: seamless integration with the activities

The focus of the activity was on the process as well as the result. As Herrington, Oliver and Reeves advise, in authentic learning

Assessment of activities is seamlessly integrated with the major task in a manner that reflects real world assessment, rather than separate artificial assessment removed from the nature of the task. (Herrington, Oliver & Reeves, 2003, p.1)

Therefore, teachers carefully monitored every stage of the work, by providing students with feedback, encouragement and stimulus, when necessary. The assessment rubric, which had been given to the students in the early stages of the course, includes these criteria: interaction and cooperation within the group; pertinence of the topic; selection and assortment of the contents; depth and insightfulness of the research; technical quality of the product; ability to present one’s project and to interest the audience; linguistic fluency and appropriacy. The evaluation was discussed explicitly in class and marks were agreed on with the students. The overall results were well above the students’ average; marks averaged 8 out of 10; some groups achieved top marks, and all obtained at least pass marks.

Besides evaluating the students’ work, the experimentation is worth assessing in terms of achievement of the objectives and of professional enrichment for the teachers. In the teachers’ view, all the objectives were achieved to a greater or lesser extent. The students’ opinion, collected through informal interviews at the end of the project and a formal survey[15] in March 2011, supported such views. In spite of spending long hours and energy on the project, all expressed appreciation for the novelty and difference of the task and found it satisfying and pleasurable. In particular, all the students answering the survey (14 out of 22) confirmed enjoying taking part in the project and stressed its usefulness to consolidate their knowledge about English literature (Bozzo, 2011, question 5); the majority agreed with the project’s role in improving their language and ICT skills (questions 4 and 6).

The development and realization of the project, though modest, has undoubtedly been very rewarding and inspiring for the two teachers, in addition to being a source of learning on both the contents of the posts and the students’ styles and personalities. For a while, the class transformed into a learning community where everybody had a relevant role and nobody, not even the teachers, prevailed.

Results: upsides and downsides

The experimentation unfolded in an increasingly positive atmosphere, where the roles of participants merged into each other; in turns, everybody was informant, consultant, learner, assessor. Decisive factors are to be found in the initial contextual motivation provided by the background and in the harmony between teachers and between teachers and class. Another very important reason is the students’ high interest and appraisal of the project, which resulted in significant involvement and commitment on everybody’s part. In the survey (Bozzo, 2011, questions 7 and 9) students underlined their good and even very good opinion of the project and the approach in general.

The major advantages highlighted by the combined employment of the information technologies and the application of constructivist principles in the experience are: the heightened opportunities for cooperation, the social negotiation of meaning and the social construction of knowledge through the usage of shared computer resources; the independent creation of one’s network of knowledge by means of personal research instead of passively receiving others’ views; the multiplicity of the means of expression, which allows to organize, build and represent one’s knowledge through a creative process; the permanence of the acquired competences and knowledge, which may become lifelong tools.

However, the experience was not exempt from shortcomings. First of all, the careful planning of such types of activities may be very time-consuming on the teachers’ side. Similarly, the proportion between the energies employed and the resulting gains may seem imbalanced. In addition, objectivity and accuracy in the assessment of the very diverse processes and outcomes appear very difficult, if not altogether impossible.

The most worrying drawback to the project as it was designed was the fact that two of the groups were very late with their work and eventually presented a product which did not fully satisfy the requirements; a higher number of lab sessions and a stricter application of the principles of cooperativeness would probably have helped the teachers detect the problems and eased the students’ difficulties. Another mild source of trouble was some students’ low computer literacy – they all overcame their difficulties through peer help; however, the provision of suitable tutorials might have prevented such technical hitches. Finally, the time devoted to the final presentations was too limited; as a result, some extra sessions had to be scheduled in the afternoon, when unfortunately not everybody could attend.

Dissemination and discussion

In addition to the aforementioned advantages, the publication of the blog allowed students and teachers to present and discuss their work with a wider audience. All the students participating in the survey (Bozzo, 2011, question 8) – except for one who skipped the question – declared they had shown their work to someone else (friends and schoolmates 76.9 %, family 69.2 %, other teachers 23.1 %). Very sadly, one student commented as follows:

Just one thing: every time I tell about it to my new schoolmates they don't care. It's just one step beyond. Contemporary for the theme (fragmentation), for the culture background that it gave us and for the media you've chosen.

It might be then inferred that, despite a theoretical background dating back more than twenty years, the methodology is still so little widespread, in Italy at least, that not even young people have the conceptual tools even to show interest.

On instances of informal talks with colleagues, the state teacher and the consultant collected mixed comments. The positive feedback about the Project Fragmentation in itself and enthusiasm about the “innovative” character of the approach were counterpointed by objections about the feasibility of such experiences and the measurability of the results, and by teachers’ lack of confidence about their own competence and fears of loss of face.

When submitted to the judgment of mentors,[16] the feedback was very positive, even though they observed that the quality of certain posts was less than good. It is probable that excessive emphasis on processes misled teachers to overestimate some final products.

Though less than perfect, the project demonstrated the effectiveness of the approach. The results are good enough to encourage further experimentation in the light of the pros and the cons, and to spur further dissemination so as to share teaching experiences with colleagues and gradually convert the “non-believers”. To conclude with a student’s comment from the survey,

I really enjoyed this project. I think it's a good way to really get into the right mindset to deal with a school program in particular (in this case English literature).

References

- 5C 2010 Project Fragmentation (n.d.). Class 5C presents its final projects inspired by this school year's programme “Fragmentation” on XXth and XXIst century art and literature. http://5c2010projectfragmentation.blogspot.com

- Anderson, L.W. and Krathwohl, D.R. (ed.) (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

- Bach, G. (2005). Whole Person, Whole Language – Fragmented Theories: Common and scientific paradigms of holistic language learning. In C. Penman (ed.), Holistic Approaches to Language Learning, (pp.15-34). Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V.S. Ramachaudran (ed.), Encyclopedia of human behaviour, Vol. 4, (pp. 71-81). New York: Academic Press.

- Bloom, B.S., et al. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay.

- Bozzo, L. (2011). Survey on 5C Project Fragmentation. Unpublished document. See at Appendix 2.

- Council of Europe (2001). CEFR – Common European Framework for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Source/Framework_EN.pdf

- Cohen, E. (1994). Designing Groupwork – Strategies for the heterogeneous classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind. The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York: Basic Books Inc.

- Glasersfeld, E. von (1989). Constructivism in Education. In T. Husen & T.N. Postlethwaite (eds.), International Encyclopedia of Education, Supplement Vol. 1, (pp. 162-163). Oxford/New York: Pergamon Press. http://www.vonglasersfeld.com/114.

- Herrington, J.; Oliver, R. and Reeves, T.C. (2003). Patterns of engagement in authentic online learning environments. In Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 19(1), (pp. 59-71). http://www.ascilite.org.au/ajet/ajet19/herrington.html

- Johnson, D.W. and Johnson, R.T. (1999). Learning Together and Alone: Cooperative, competitive and individualistic learning. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. and Holubec, E.J. (1994). The New Circle of Learning: Cooperation in the classroom and school. Alexandria: ASCD.

- Krashen, S.D. and Terrell, T.D. (1983). The Natural Approach: Language acquisition in the classroom. Oxford: Pergamon.

- Papert, S. (1989). Constructionism: A new opportunity for elementary science education. [abstract]. National Science Foundation. http://nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward.do?AwardNumber=8751190

- Ramsbottom, K. (2009). Programma Project Fragmentation A.S. 2009-2010. Unpublished document, see at Appendix 1.

- Skehan, P. (1998). A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning. Oxford: OUP.

- Slavin, R.E. (1995). Cooperative Learning: Theory, research and practice. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wikipedia the Free Encyclopaedia (nd). Constructionism (learning theory). Last retrieved on 27 December 2007 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constructionism_%28learning_theory%29.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Kirsty Ramsbottom for being extremely supportive throughout the project and for suggesting many of the ideas in it. Naturally, I am very indebted to all the students from class 5C 2009-10, without whom nothing of this would have been possible. I wish to thank Prof. Donatella Abbate Badin, Prof. Virginia Pulcini and Daniela Salusso for their careful reading and comments on the paper.

Appendix 1: Project Contents

Programma Project “Fragmentation” a.s. 2009 – 2010

Expressions of personal experience in the 20th century in literature, art, music and film

MODULE ONE: Background to the 1st World War

- Film clip from YouTube – diary excerpt “the horrors of the trenches”

- Poems – Wilfred Owen “1914” and “Dulce et Decorum Est”

- Wartime propaganda – Song – Marie Lloyd, “When you’ve got the Khaki on”

- Coming home – devastation, uncertainty, injury

- Homework – students write a letter from the trenches

MODULE TWO: Art and Music in the postwar period – broken images

- Picasso, Braque – looking at pictures – group work

- Stravinsky, Leger – experimentation with expression

- New Movements – Group work

- Futurism, Surrealism, Dadaism, Suprematism, Vorticism

MODULE THREE: Modernist Poetry

- The Second Coming by W.B. Yeats

- The Hollow Men by T.S.Eliot

- Film Clip – Control by A.Corbijn

- The Mythical Method – piecing together the broken world

- What do we mean by MODERNISM? Worksheet

MODULE FOUR: The Beat Generation

- On the Road by J.Kerouac

- Howl by Allen Ginsberg

- Film Clip – Easy Rider

- Post-modernism – chaos and optimism

MODULE FIVE: The 1960s

- Youth Protest and Rebellion

- Antiwar protests and songs

- A Taste of Honey – Shelagh Delaney

- Pop Art

- Film clip – Woodstock

MODULE SIX: Post Colonialist Writers

- Things Fall Apart Chinua Achebe

- Derek Walcott

MODULE SEVEN – sampling and mixing from the past

- 24 hour party people (film)

- 1990s and Rave Culture

- Trainspotting – Irvine Welsh

- New Age Travelers

- The new poets – Hip-hop/Rap

MODULE EIGHT: Personal experience today

- Blogs, YouTube, Social networking

FINAL PROJECT – YOUR interpretation of “fragmentation”

Appendix 2: Survey 5C blog fragmentation

Questions |

Suggested Answers |

Students’ Answers |

Percentage |

2. Do you remember working for the Project Fragmentation Blog last schoolyear? |

Yes, very well |

11 |

78.6 % |

Yes |

3 |

21.4 % |

|

Only vaguely |

0 |

0 % |

|

No |

0 |

0 % |

|

Total |

14 |

100 % |

|

3. Did you like working at the blog project? |

Yes, very much |

8 |

57.1 % |

Yes, rather |

6 |

42.9 % |

|

Not much |

0 |

0 % |

|

Not at all |

0 |

0 % |

|

Total |

14 |

100 % |

|

4. Do you think the project blog was useful to improve your English language? |

Very useful |

1 |

7.1 % |

Quite useful |

9 |

64.3 % |

|

Not very useful |

4 |

28.6 % |

|

Useless |

0 |

0 % |

|

Total |

14 |

100 % |

|

5. Do you think the project blog was useful to consolidate your knowledge about English literature? |

Very useful |

6 |

42.9 % |

Quite useful |

8 |

57.1 % |

|

Not very useful |

0 |

0 % |

|

Useless |

0 |

0 % |

|

Total |

14 |

100 % |

|

6. Do you think the project blog was useful to improve your multimedia and computer skills? |

Very useful |

5 |

35.7 % |

Quite useful |

6 |

42.9 % |

|

Not very useful |

3 |

21.4 % |

|

Useless |

0 |

0 % |

|

Total |

14 |

100 % |

|

7. Give a mark (from 2 to 10) to the overall effectiveness of the project fragmentation blog activity. |

10 |

1 |

7.1 % |

9 |

4 |

28.6 % |

|

8 |

7 |

50.0 % |

|

7 |

2 |

14.3 % |

|

6-2 |

0 |

0 % |

|

Total |

14 |

100 % |

|

8. Have you ever shown your work or the blog to any of the following? |

Schoolmates |

10 |

76.9 % |

Friends |

10 |

76.9 % |

|

Family |

9 |

69.2 % |

|

Other teachers |

3 |

23.1 % |

|

No one |

0 |

0 % |

|

Other |

0 |

0 % |

|

Total |

13 |

92.9 % |

|

9. In general, do you consider computer/multimedia/internet activities like the project fragmentation blog as effective teaching techniques? |

Very effective |

9 |

64.3 % |

Quite effective |

5 |

37.5 % |

|

Not very effective |

0 |

0 % |

|

Ineffective |

0 |

0 % |

|

Total |

14 |

100 % |

|

10. Feel free to add any comments about the project fragmentation blog.[17] |

The Best English prof. ever! Grande Prof |

||

Just one thing: every time I tell about it to my new schoolmates they don’t care. It’s just one step beyond. Contemporary for the theme (fragmentation), for the culture background that it gave us and for the media you’ve chosen. |

|||

Project fragmentation blog is very effective because is an innovative and interesting way of teaching English literature |

|||

I really enjoyed this project. I think it’s a good way to really get into the right mindset to deal with a school program in particular (in this case English literature) |

|||

Interesting project but in my opinion not very useful to improve my English. thanks to it I learned new things about English literature |

|||

It was good mostly because it was new!!! |

|||

Total |

6 |

42.9 % |

|

[1] As for the contents of this paragraph, I am indebted to Caterina Poggi’s materials “Paradigmi di Apprendimento Supportati dalle Tecnologie” from the course DOL – Diploma on Line per Esperti di Didattica Assistita dalle Nuove Tecnologie, www.dol.polimi.it.

[2] The Project Fragmentation course’s programme outline, by Kirsty Ramsbottom, is in this paper’s Appendix 1.

[3] The website of the school, www.istitutoaltierospinelli.eu, provides information concerning the school’s special organization and programme.

[4] For the organization and some of the contents of this paragraph I am indebted to Carmel Mary Coonan’s materials produced for the University of Venice course LADILS 2009-10 – Corso di Perfezionamento – Insegnamento delle LS.

[5] A description of the cooperative learning approach may be found in Slavin (1995).

[6] For the theory of multiple intelligences, see Gardner (1983).

[7] An overview of theories and models of cognitive styles is provided in Skehan (1998).

[8] The Affective Filter Hypothesis is presented by Krashen and Terrell (1983).

[9] Self-efficacy is defined by Bandura (1994) as a person’s belief in their own competence.

[10] Second Language Acquisition – there were no English native speakers in the class.

[11] A holistic language learning approach is aimed at providing a rich learning environment through a variety of methodologies and techniques (Bach, 2005).

[12] See in this paper’s Appendix 1.

[13] Several authors, among which Cohen (1994), recommend that groups are as heterogeneous as possible, and therefore suggest that teachers find ways to take decisions about group composition.

[14] The blog posts, most of which are videos, are visible at http://5c2010projectfragmentation.blogspot.com

[15] See in this paper’s Appendix 2.

[16] A report on the project was submitted to the staff of the Italian course DOL – Diploma on Line per Esperti di Didattica Assistita dalle Nuove Tecnologie, www.dol.polimi.it.

[17] Students’ language mistakes have been deliberately maintained.