Interaction Equivalency in the OER and Informal Learning Era

Terumi Miyazoe, Tokyo Denki University, Japan,

Terry Anderson, Athabasca University, Canada

Abstract

In this theoretical paper, we overview the application of the Anderson’s 2003 Interaction Equivalency Theorem (the EQuiv) to the development and student use of formal online learning. The EQuiv theorem explains how the effective use of OERs, MOOCs and net-based video can be used to enhance institutional-created content at low cost and high efficiency.

Abstract in Japanese

本論文は、正規教育におけるオンライン学習の発達および学習者による使用状況を、テリー・アンダーソンが2003年に提唱したインタアクション等価説(Interaction Equivalency Theorem: 通称 the EQuiv)を用いて概観する。 Equiv により、教育機関が作成する教育コンテンツをOERs (Open Educational Resources: オープン教育リソース) 、MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses: ムークス)、そしてインターネット配信ビデオを活用しいかに安価かつ効率よく効果的に強化できるかを説明する。

Key Words: EQuiv, Interaction Equivalency Theory, OERs, MOOCs

Introduction

This paper aims to clarify issues and challenges that the field of education has encountered in the context of OER (Open Educational Resources) and increased emphasis on informal learning (Eraut, 2004). It is guided by insights from the Interaction Equivalency Theorem (the EQuiv) posited by the second author (Anderson, 2003). In the paper, we first provide an overview of the core concepts of the EQuiv. Next, we explain how the EQuiv framework can be used to analyze interaction designs for online and distance education. Furthermore, relying on the functionality of the EQuiv, the paper examines the major challenges and opportunities formal education is confronting due to the ever-growing availability of OER and informal learning opportunities they create (Anderson & McGeal, 2012). In conclusion, this paper explores the changing role of formal education in the new era of learning where large quantities of online educational resources and opportunities are readily accessible and in many cases completely free of cost to the learner.

Interaction equivalency theorem

Definitions and concepts

The Interaction Equivalency Theorem (the EQuiv) was originally posited by Anderson (2003). In this paper the definition of interaction provided by Wagner (1994) is used, which is the one Anderson adapted to develop his interaction arguments. That is, interactions are “reciprocal events that require at least two objects and two actions. Interactions occur when these objects and events mutually influence each other” (p. 8).

Historically, the Three Types of Interaction model (Moore, 1989) was the first systematic use of interaction as a defining quality and characteristic of distance education. This model defines critical interaction in educational contexts as having three essential components: learner–content, learner–instructor, and learner–learner interaction. As an extension of Moore’s model, the EQuiv was created with the purpose of providing “a theoretical basis for judging the appropriate amounts of each of the various forms of possible interaction”. For a detailed history of interaction theory, please refer to Miyazoe (2012).

The main features of the EQuiv are condensed into two theses:

- Thesis 1. Deep and meaningful formal learning is supported as long as one of the three forms of interaction (student–teacher; student–student; student–content) is at a high level. The other two may be offered at minimal levels, or even eliminated, without degrading the educational experience.

- Thesis 2. High levels of more than one of these three modes will likely provide a more satisfying educational experience, although these experiences may not be as cost- or time-effective as less interactive learning sequences.

Interpretations of the EQuiv in various contexts have formed the basis of a number of research studies and student thesis. Many of these are linked at the Equivalency Theory site at http://equivalencytheorem.info.

In accordance with the EQuiv formulation, Anderson had expanded Moore’s interaction model to all possible six components: student–content, student–teacher, student–student interaction, plus teacher–content, teacher–teacher, and content–content interaction (Garrison & Anderson, 2003).

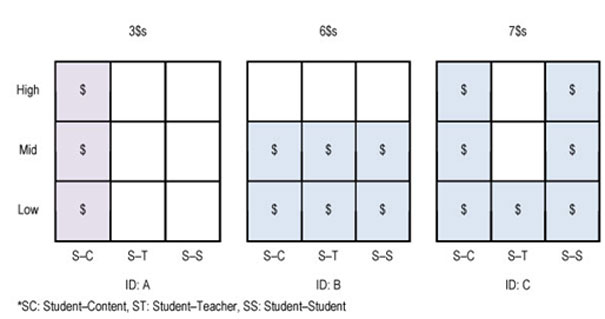

Figure 1 is an attempt to visualize the two EQuiv theses. The figure on the left represents Thesis 1 and its two main points: (a) in its extreme, a high level of one of the interactions (i.e., student–teacher, student–student, and student–content) is able to support insightful, meaningful formal learning, and (b) each interaction has the same value (equivalency = equal + value), which is denoted by using the equal sign. Additionally, the colored shading highlights the difference in the various intensity levels (high, middle, and low) of interactions: a deeper hue signifies a higher level of interaction intensity. The figure on the right represents Thesis 2, which is the following: more than one type of high-level interaction is desirable in order to increase learner satisfaction. The component of cost/time efficiency will be detailed in the next section.

It is important to emphasize that the main point of Thesis 1 is concerned with the effectiveness of learning (that is, the qualitative aspect of the educational interaction). By contrast, Thesis 2 is concerned with learner satisfaction and cost/time efficiency (quantitative). In addition, Terry Anderson originally meant for the cost/time concept to be applicable for both program providers (including institutions and tutors) and learners.

Figure 1. The EQuiv Visualization

EQuiv and cost/time issues

Interaction is expensive in any format and has time, financial and opportunity costs for learners, teachers and institutions. Instructional design refers to the entire process of achieving educational outcomes (Siemens, 2002) and thus includes consideration of interaction costs. By contrast, interaction design (ID) is focused on the specific course/curriculum design for learning. When we plan for an increased amount of interaction in an educational course (for example, a higher frequency of Q&A between teacher and students using an online forum or a higher frequency of socialization among students using social networking space), additional cost/time is required.

Figure 2. Cost/Time Issues in Interaction Design

In Figure 2, let us suppose that ID: A is the most efficient design (it has achieved the highest level of learning with the least cost/time), and ID: C is equally effective (it achieves the same high level of learning) and satisfactory (due to the variation of high-level interaction) for a specific purpose in a particular context. In many cases, the ID used could be ID: B, in which a moderate level of all the three interactions is implemented with the hope that the ID will satisfy the needs and expectations of the highest number of stakeholders. It is important that the EQuiv considers that the optimal ID will likely be different, depending on numerous variables in a specific context (Miyazoe & Anderson, 2010; Miyazoe & Anderson, 2012). However, ID: B and C could be less desirable if both effectiveness and efficiency are demanded.

The EQuiv in the contexts of OER and informal learning

We noted the effect of OER and informal learning potentials in the EQuiv when we discussed closed versus open systems in educational resource provisions:

“The conceptualization of the theorem clarifies further dimensions that need to be considered in the interaction design. One of these dimensions is the diversity of educational delivery contexts (i.e., closed vs. open systems). In a closed system, due to the limitations of cost and other resources, the designer may have to choose which possible interaction is the most important. In an open system, positive and accidental interaction Thus (e.g., a course teacher voluntarily adding new online resources or a student enhancing learner-interaction through watching Kahn Academy videos) to enhance the course) are possible. The cost and time issues are relative to the system chosen as the framework of the course design” (Miyazoe & Anderson, 2011, p.2).

These interaction surpluses are educational examples of new affordances that authors such as Clay Shirkey refer to as cognitive surplus or Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014) call a bounty. They provide more tangible goods, digital products and services all at lower and lower price. The availability of the ever-growing OER and informal learning opportunities relate to this opening of the traditional education systems, which notes the accidental interaction surpluses are increasingly important variables to be taken into the formal educational curricula and systems. Educational institutions are becoming networks of information and knowledge aggregation where partially open educational systems are digitally connected to each other. The Modes of Interaction model posited by Garrison and Anderson (2003) is useful to analyze the various types of learners with the new OER and informal opportunities alongside formal learning:

- Student–Content: Increasingly, students are being asked and challenged to both find and create content and to share this as OERs that can enhance and augment the content supplied by the course creators.

- Student–Teacher: Students gain a teacher-like presence from various sources (recordings of other teachers, MOOCs, etc.) other than the formal teacher even though the issue of responsibility, morality, integrity, accuracy, bias etc. can be confusing to students.

- Student–Student: Numerous online platforms for socialization are available, and students can achieve a high-level of interaction among peers within and beyond those enrolled in the course in various ways outside of the formal curricula.

- Teacher–Content: Teachers (or course developers) are able to collaboratively create and use content through tools like Wikis and OERs that allow them to both create and use multiple types of content.

- Teacher–Teacher: Numerous online resources and platforms allow teachers to interact and learn within networked communities of practice and to assess and recommend content and activities among the set of distributed teachers (Dron & Anderson, 2014).

- Content–Content: With digital networks, content itself is potentially interactive and can be designed to update and augment other content thus growing prolifically beyond the formal/informal distinction.

The current issues and challenges that formal education systems have/will face amid expansion of OER and informal learning will next be examined using the EQuiv framework of learning outcomes (Thesis 1), learner satisfaction and cost/time issues (Thesis 2).

Learning outcomes

In current formal learning environment OER and informal learning opportunities abound. Students can rely on a high-level interaction of many kinds from various resources without major limitation. In this context, Thesis 1 remains valid because its primary focus is on quality; the difference in material location (inside/outside of school) and learning mode (formal and informal) are peripheral to the issue. This also signifies that quality learning can occur even if formal education fails to provide the necessary intensity of interaction as the learner knows he/she has opportunity to access external means to supplement to any expected or required level of interaction. For example, a student in a formal course may access content from iTunes University, a MOOC, Khan Academy, an international network of students studying in the discipline or an online forum of professional interaction. In this sense, the realization of quality learning has become more dependent on each learner’s ability and their network literacy (Kjærgaard & Sorensen, 2014). This begins with choosing the best formal program that fits his/her needs and extend to creative augmentation of the best available OER and informal learning opportunities.

Learner satisfaction

As we saw above, Thesis 2 suggests that having more than one kind of high-level interaction is likely to be associated with higher learner satisfaction. With OER and informal learning opportunities, when a program provides only one kind of high-level interaction, students can gain a higher level of satisfaction by using other kinds of high-level interactions from outside sources. Take, for example, the flipped classroom in which students acquire both information and knowledge through searching for OER in order to complete tasks or assignments and then use the formal course time for topical discussion. Hypothetically, the student’s satisfaction level would be quite high, while costs are constrained. This has been shown in a number of recent studies of blended learning and flipped classrooms in a variety of contexts (Bishop & Verleger, 2013; Street, Gilliland, McNeil, & Royal, 2015; Butt, 2012). Therefore, like learning outcomes, an individual learner gains high satisfaction from any formal or fixed learning design depending upon his/her ability to obtain and effectively utilize an additional surplus. This could further be facilitated if the provider (course tutor, content designer, etc.) provides training in OER selection and a helpful resource bank for consultation, student recommendation and augmentation.

Cost/time issues

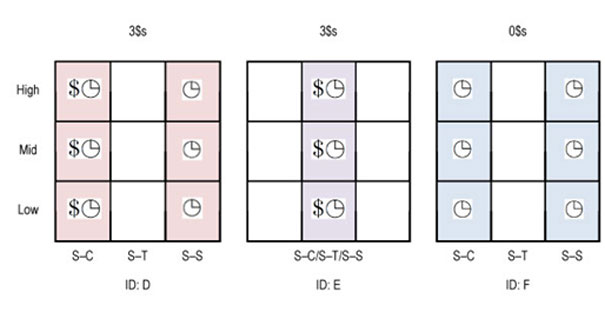

Since interaction has both cost and time components, the cost/time issues warrant an in-depth, complex analysis, particularly when OER and informal variables are involved. The dollar sign symbol represents cost; whereas, the clock symbol represents the time spent during an interaction.

Figure 3. EQuiv in OER and Formal Learning

The figures in Figure 3 represent three hypothetical cases of high-level interaction:

- ID: D (the left side) – The formal program provides high-level interaction Student Content (S-C), and high level Student–Student (S-S) is provided in some way (by the program or through learner initiative). This model is practiced in many commercial MOOCs. MOOC financial models are evolving but will likely focus on advertising and sale of auxiliary product.

- ID: E (the middle) – The formal program provides a high-level interaction of one kind, and the learner is committed only to this format. This format is offered for example, by purchase of a training package delivered via video, CAI or text.

- ID: F (the right side) – High-level quasi-cost-free interaction of two kinds are used at the learner’s initiative as for example, by engagement in a set-based Learn.ist cluster, supplemented by a local study group.

Following the EQuiv theses, ID: E is a design in which the educational institution is concerned and tasked with creating high quality; whereas, ID: D is a design that is focused on maintaining an equal level of quality learning, but provided by the institution creating high quality content and encouraging the student to find their own S–T and S–S support. However, we should note that a higher level of satisfaction is not cost-free: it consumes more time of the learner, which is not free but precious because learners in online and distance education are often persons with both employment and domestic responsibilities. Opportunity cost (Matkin, 1997) applies to everyone – time spent studying precludes engaging in other activities. In other words, in terms of time efficiency, with ID: E, students spend only 3 dollar-time units (DTUs) for one kind of high-level interaction to complete the formal requirements; whereas with ID: D, students spend 3 DTUs for high-level S–C interaction to fulfill the formal course requirements plus 3 DTUs for high-level S–S interaction outside but paying 3 DTUs for the formal part only; with the ID: F design, although it may be inexpensive for the active use of OER and others, the learner may have spent twice as much time, that is, 6 DTUs, though they may pay quasi-zero dollars in reality, to gain a level of learning similar to ID: E. In sum, there are visible and invisible costs and the learner could spend more (of either of these scarce resources) to gain the same, or worse, less. This invisible time-cost does exist all the time but the OER and informal learning opportunities make the extent of this invisibility more pervasive.

It is worth noting that the same argument also applies to the teacher experience. With no or low cost for additional interaction for the educational providers, those surplus interactions are more likely to be suggested as options rather than requirements. That is, the surpluses may appear to be cost-free, but in actuality, they are volunteer activities that consume the teacher’s time.

And when we go back to Thesis 2, more than two kinds of high-level interaction increase the level of satisfaction. On the other hand, the level of satisfaction depends on the time-cost efficiency as well, where satisfaction level differs learner to learner: for those who value time, even if ID: D and ID: E cost the same, ID: E may be more satisfactory. In the same way, those who value time prefer choosing ID: D over ID: F even if he/she has to pay because ID: D saves valuable time. In other words, in the OER and informal era, time-cost efficiency becomes even more critical in choosing the best formal learning experience. The quality-time-accessibility triangle posited by Daniel (2003), in reference to the external vectors of education and mega-universities, may now be re-phrased as both institutional vectors and the individual learner vectors of quality-time-cost especially in the places where the issue of accessibility is more attenuated by the Internet.

Discussion and further direction

From the EQuiv perspective, it seems apparent that formal education should and indeed must cost less if it hopes to survive in an era when alternative forms of free educational opportunities grow rapidly. However, time is money principle suggests that the time needed to achieve quality learning may remain consistent in this new era of learning. Additionally, this paper admits that there needs to be a higher level of a learner control over his/her learning design by creating necessary surpluses as well as reductions in order to produce learning at the highest level of effectiveness and efficiency. For this to be achieved, there needs to be a high quality of learning resources available and learner must have high levels of time management skills and network literacies. In sum, the ability to manage the cost and the time for learning is becoming extremely critical to both formal students and lifelong learners in this emergent world of network-enhanced learning.

In this context of new learning, how does the formal education claim its raison d’être? The answer implied in this paper is to provide education that creates adaptable models of high-level interaction – but allows the learner to augment or choose adaptations that meet their time and money constraints and resources. In other words, select Thesis 1 and adhere to it. This minimalism seems to be the only way to survive in the ever-tightening world economy, constantly diminishing public support for higher education and increasing needs for life-long learning opportunity. Consequently, for learners who have acquired the skill of managing his/her learning, the formal educational system is losing its traditional status and authority as the only authentic education provider. It is time that we accept this change and re-create our institutions for service and success in a networked, lifelong learning context.

Resource-sharing

We have created a web site that collects references and resources for studies relevant to the EQuiv (http://equivalencytheorem.info). We welcome people who have a serious interest in the research regarding the EQuiv. We invite you to contact us at this website for further information sharing and collaborative research projects regarding the development of the EQuiv.

References

- Anderson, T. (2003). Getting the mix right again: An updated and theoretical rationale for interaction. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 4(2). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/149/230

- Anderson, T., & McGreal, R. (2012). Disruptive Pedagogies and Technologies in Universities. Educational Technology & Society, 15(4), 380–389.

- Bishop, J. L., & Verleger, M. A. (2013). The flipped classroom: A survey of the research. Paper presented at the ASEE National Conference Proceedings, Atlanta, GA.

- Butt, A. (November 8, 2012). Student Views on the Use of Lecture Time and their Experience with a Flipped Classroom Approach. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2195398 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2195398

- Brynjolfsson, B., & McAfee, A. (2014). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. New York: Norton & Company.

- Daniel, J. (2003). Mega-universities = mega-impact on access, cost and quality. Retrieved from http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/ev.php-URL_ID=26277&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

- Dron, J., & Anderson, T. (2014). Teaching crowds: Learning and social media. Edmonton, Canada: Athabasca University Press. Retrieved from http://www.aupress.ca/index.php/books/120235

- Eraut, M. (2004). Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 26(2), 247-273. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/158037042000225245

- Garrison, D. R., & Anderson, T. (2003). E-learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice. New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Kjærgaard, T., & Sorensen, E. K. (2014). Rhizomatic, digital habitat-A study of connected learning and technology application. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on e-Learning: ICEL 2014. https://http://www.researchgate.net/publication/262945019_Rhizomatic_digital_habitat_-_A_study_of_connected_learning_and_technology_application

- Matkin, G. W. (1997). The Basics of Course Financial Planning. In G.W. Matkin (Ed.), Using Financial Information in Continuing Education: Accepted Methods and New Approaches (pp. 65-83). Phoenix, AZ: American Council on Education/The Oryx Press.

- Miyazoe, T. (2012). Getting the mix right once again: A peek into the interaction equivalency theorem and interaction Design. Retrieved from http://newsletter.alt.ac.uk/2012/02/getting-the-mix-right-once-again-a-peek-into-the-interaction-equivalency-theorem-and-interaction-design/

- Miyazoe, T., & Anderson, T. (2010). Empirical research on learners’ perceptions: Interaction equivalency theorem in blended learning. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 2010/I. Retrieved from http://www.eurodl.org/index.php?p=archives&year=2010&halfyear=1&article=397

- Miyazoe, T., & Anderson, T. (2011). The interaction equivalency theorem: Research potential and its application to teaching. Proceedings of The 27th Annual Distance Teaching & Learning, Madison, WI.

- Miyazoe, T., & Anderson, T. (2012). Interaction equivalency theorem: The 64-interaction design model and its significance to online teaching. The 26th Annual Conference of Asian Association of Open Universities Proceedings, Makuhari, Chiba. (CD-ROM).

- Moore, M. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction. The American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1-7.

- Siemens, G. (2002). Instructional design in elearning. Retrieved January 21, 2013, from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/InstructionalDesign.htm

- Street, S., Gilliland, K., McNeil, C., & Royal, K. (2015). The Flipped Classroom Improved Medical Student Performance and Satisfaction in a Pre-clinical Physiology Course. Medical Science Educator, 25(1), 35-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40670-014-0092-4.

- Wagner, E. D. (1994). In support of a functional definition of

interaction. The American Journal of Distance Education, 8(2), 6-26.