An Exploration of Tutor Feedback on Essays and the Development of a Feedback Guide

Anthea Wilson, The Open University, United Kingdom

Abstract

Feedback on student essays is a central aspect of learning in higher education, and feedback quality is important. An evaluation of existing tutor and student feedback was carried out to determine the relationship between tutor feedback summaries and students’ notes to their tutors, regarding their efforts in response to the feedback. An analytic framework was developed in conjunction with content analysis of these naturally occurring data. Categorising and mapping the categories of feedback longitudinally revealed diverse feedback patterns and trends of diminishing future-oriented feedback during the course. Personal qualitative engagement with the data also revealed examples of unclear feedback. Subsequently, a guide was developed in order to unpack the language surrounding academic writing skills. The guide was piloted with ten volunteer tutors. The study concludes that unpacking the academic language that is frequently applied to writing skills, will support conversations between tutors and students as well as amongst academics.

Keywords: academic essay; assessment; feedback construction; distance learning; content analysis

Introduction

The provision of appropriate feedback on assessed work to students in higher education has long been a topic of concern. Now that universities are ranked according to responses to the National Student Survey, student ratings of their feedback have acquired a new salience. It is possible, via the Unistats (n.d.) website to compare how many students responded positively to the statements ‘I have received detailed comments on my work’ and ‘Feedback on my work has helped me clarify things I did not understand’. In 2014, inspection on the Unistats website of a sample of 40 English higher education institutions offering health and social care courses indicated that receiving detailed comments usually, but not always, outscored the ability of feedback to clarify understanding. This reflects the finding of research (e.g. Sadler, 2010) showing that feedback does not necessarily lead to improvement and that more is not always better.

The Open University has a reputation for excellence in the assignment feedback provided to students (Gibbs, 2010); however, ongoing experience of Open University academics is that students do not always appear to be responding to, or even in some cases reading, the tutor feedback. As established by Hattie and Timperley (2007), an essential aspect of providing feedback is discovering how students have interpreted it. In the [organisation] distance-learning context, students typically do not contact their tutors to discuss the feedback on their assignments and frequently tutors are working somewhat in the dark with respect to how their feedback is received. This paper discusses some of the challenges raised by this situation typically experienced within the Open University distance-learning model and reports on an investigation of patterns of tutor feedback in the context of written assignments in a health and social care module.

A second stage of the project reported here is the testing of a tool or guide intended to support tutors to unpack the academic language surrounding feedback on academic writing in student essays. For example, what does it mean if an essay needs ‘more depth’ or a student’s writing is ‘too descriptive’? How can a student replicate ‘good structure;’ next time if it is not clear what they did well last time? The tool aimed to meet three outcomes for students: to understand the rationale for their marks; to know what to work on next time and how to do it; to feel motivated to take control of and continue their studies. This paper will discuss the issues raised by a pilot study with a sample of tutor volunteers.

Background literature

In Higher Education, the essay is valued for affording explicit presentation and evidencing of ideas (Andrews, 2003). Therefore, essays should allow students to demonstrate their level of understanding and tutors to assess this. The academic essay, however, occupies contested ground. Read, Francis and Robson (2005), for example, called into question the validity and reliability of essay assessment when they found wide variation between academics in the marking of the same student essays. Tomas (2013) identified flaws in criterion-based marking systems, observing that tutors commonly applied norm-referencing alongside criterion-referencing as a form of self-monitoring. Moreover, students recognise variation between markers and can become sceptical about the credibility of feedback they receive (Poulos & Mahony, 2008). There is also potential for miscommunication between students and academics. For example, we cannot assume that students will understand the language that academics and tutors use in guidance on academic skills (Higgins, Hartley & Skelton, 2002). Despite the many reservations, academic essays have been found to support deep learning approaches, extending opportunities for students to demonstrate their intellectual skills (Scouller, 1998).

For feedback on essays to be effective, both staff and students need to share an understanding of its purpose, whether for correction, behavioural reinforcement, diagnosing problems, benchmarking or longitudinal development (feed-forward) (Price et al., 2010). According to Price et al. (2010) in their study of three university business schools, both students and tutors aspired to give or receive forward-feeding developmental feedback, although in reality diagnosis and benchmarking predominated. This observation was partly attributed to the linkage of formative and summative assessment: summative assessment is more likely to demand that feedback provides justification for the marks. Moreover, there is evidence that tutors are just as likely to write their justifications for external observers as for students (Bailey & Garner, 2010; Tuck, 2012) and therefore their feedback is not only tailored to a student’s requirements. One can infer that in order to improve feedback effectiveness, a starting point is to ensure that all concerned share an understanding of the expectations of academic writing in a particular discipline (Itua et al., 2014).

Numerous scholars have explored how to improve feedback on essay writing. Walker (2009), for example, claims that tutors need to pay more attention to explanations to qualify their positive or negative comments on the script. Structured feedback is also promoted as good practice. Part of the success of Norton’s structured Essay feedback checklist, for example, is attributed to helping steer students with greater precision and to help students understand assessment criteria (Wakefield et al., 2014). Further studies of feedback on student assignments have highlighted retrospective feedback (feedback on the specific content and skills demanded by the assignment) outweighing that which is future-altering (feedback on generic skills and content), and a deficiency in feedback on skills (Chetwynd & Dobbyn 2011). It has been argued that such imbalances may impair students’ chances to respond positively in developing their academic writing skills (Walker, 2009) as well as their broader learning strategies (Lizzio & Wilson, 2008), and therefore that much more attention needs to be paid to skills.

In addition to the technical and structural aspects of written feedback, there is also widespread recognition of the influence of the affective domain in feedback practices (Carless, 2006; Molloy, Borrell-Carrió & Epstein, 2013). Cramp, Lamond, Coleyshaw and Beck (2012) found that potent emotions associated with assessment can be disabling for students. Emotions such as fear of failure or a sense of actual failure can interfere with a student’s interpretation of feedback (Knight & Yorke, 2003), and awareness of this student vulnerability can also result in tutors delivering feedback designed to preserve a student’s dignity (Molloy et al., 2013). Moreover, it has been established that ‘first-year’ students particularly need to be supported in the emotional aspects of learning, such as when receiving and interpreting assignment feedback (Cramp et al., 2012; Poulos & Mahony, 2008). Barnett (2007) has offered further insights, suggesting that there is performance involved in the act of assignment writing. The ‘performance’ is two-fold: ‘reaching out to an audience’ (mainly the tutor) and the performance involved in using language to create academic arguments (Barnett, 2007 p.79). Barnett also discusses the element of personal investment in academic work, proposing that submitting an assignment is an act of proffering a gift. His suggestion that students are vulnerable to fear of rebuke and criticism in response to the ‘gift’ of an essay provokes further reflection on the transactional nature of assessment.

The context of the study

K101 ‘An introduction to health and social care’ is a core introductory undergraduate module for the Faculty of Health & Social Care at The Open University. As well as providing an overview of experiences and practices in health and social care and introducing theoretical concepts, K101 also has a role in developing study skills in a way that is accessible to a non-traditional audience. The continuous assessment strategy, involving seven written assignments over an eight-month period, was designed explicitly to provide frequent opportunities for students to practise academic writing and obtain both formative and summative feedback. Additionally, K101 is a component of The Open University’s social work degree, in which the professional body mandates that all tutors provide feedback to students on the standard of writing in their assignments. During a project aimed at providing targeted writing development support for K101 students who were particularly challenged by academic essay writing, it became apparent that the technical aspects of essay writing could not be separated from students’ personal struggles to understand the content of the module, the expectations of assessed work, and what it means to study at HE level.

We realised that K101 students might not always understand or be able to respond productively to the written feedback. It became clear that there was a chain of communication events, each of which was vulnerable to misinterpretation, from the intentions of the central academic writing the question (including the student guidance and tutor marking guidance) to the diverse understandings of the genre of essays in HSC and what constituted a good essay. Small-scale investigations of the student experiences of writing essays and tutor experience of supporting essay writing at the Open University (e.g. Donohue & Coffin, 2012), indicated that students, central academics and tutors could potentially make very different sense of the requirements of an essay task.

In 2011/12 the introduction of self-reflective questions in two K101 tutor-marked assignments (TMAs), aimed at encouraging students to engage with their tutors’ feedback and reflect their responses back to the tutor, provided an opportunity to evaluate an aspect of the student-tutor dynamic within this process. The questions, included in TMA02 and TMA07, focused on students’ perceptions of their responses to their tutor’s feedback. In both TMAs, students were asked to give very short answers to the questions ‘What aspects of your tutor’s advice from previous feedback have you tried to use in this assignment?’, ‘What have you found most difficult about this TMA?’ and in TMA07 only, ‘How do you view your progress since you started K101?’ The focus of the first part of this paper is on the observable distance-tuition interface between student and tutor. It analyses the tutor feedback and the insights students reflected back to their tutors. The second part summarises a pilot implementation of a tool to facilitate structured explicit and meaningful feedback in K101 essays.

Stage 1: exploring feedback practices and explicit student responses

Aims

This first stage aimed to evaluate the relationship between tutor feedback summaries on student essays and student responses to the self-reflective questions. Trends in retrospective and future-oriented feedback, and content and skills feedback were explored through the course.

Method

In this longitudinal evaluation study using naturally occurring data, random samples of tutor feedback summaries were systematically content-analysed for ‘content and skills’ feedback and their retrospective or future-altering orientations (Chetwynd & Dobbyn, 2011). Table 1 shows Chetwynd and Dobbyn’s (2011) matrix indicating four main feedback domains: retrospective on content or skills, and future-altering on content or skills, which has been applied to tutor marking guidance on an OU technology course. In addition, student responses corresponding explicitly to their tutor’s feedback were analysed according to the particular content or skills orientation. This was essentially a qualitative, interpretive process resulting in some quantifiable cohort data and individual student-tutor ‘cases’. The frequency with which the tutor sample commented on a particular feature, and the mode (whether retrospective or future-oriented) were mapped over time (per TMA) and against the students’ self-reflective notes. A further mode of engagement with the data involved the single investigator making personal judgements about the clarity, meaningfulness and navigability of the feedback.

Table 1: A feedback matrix, from Chetwynd and Dobbyn (2011)

Retrospective |

Future-altering |

|

Content |

||

Skills |

Analytic framework

Taking Chetwynd and Dobbyn’s (2011) matrix as a starting point, the ‘skills’ element was further subdivided during engagement with the feedback samples to take account of the range of writing skills being developed in the course and the clear distinctions being made by the tutors in their feedback. Note that tutors also provided comments on the script, but these were not included in the study because the purpose of the summaries was to draw together the observations of the scripts and present the tutors’ overall impressions of the work. The original ‘future-altering’ category was rebadged as ‘future-oriented’ in recognition of the limitations of the content analysis activity, namely that the explicit future effects of individual elements could not be determined and to recognise that all feedback was potentially future-altering. The final analytic framework applied eight ‘content and skills’ categories (see Table 2).

Table 2: Analytic matrix of content and skills categories in feedback

Content and skills |

Tutor retrospective (focused on the marked essay) |

Tutor future-oriented (framed as work for future assignments) |

Student Self-Reflective notes |

Study skills: self-organisation, study strategies, providing a word count (as good academic practice), signposting to/offering further resources or support |

|||

Referencing: all referencing skills |

|||

Cognitive skills: ways of handling content – interpreting/answering the question, defining terms, using concepts, and developing an argument |

|||

Content: use of evidence and course materials, including case material |

|||

Style: flow, signposting, clarity (beyond basic grammar issues), word contractions, and ‘voice’ (such as use of first/third person) |

|||

Structure: organisation of the essay, word count (whether the appropriate length), and paragraphing |

|||

Grammar and spelling: sentence construction and spelling |

|||

Presentation: layout and choice of font |

Sampling

Electronic tutor-marked assignments (eTMAs) were sampled by hand via the eTMA monitoring system, which itself had already randomly selected marked scripts for quality assurance monitoring. Rules applied during hand sampling were to select different tutors each time and to achieve a geographical spread across the UK. An initial sample of 52 students became depleted, due to some not submitting self-reflective notes, not downloading some feedback, or ceasing to submit TMAs. The final sample of 25 students (about 1.5 per cent of all course completers), each with different tutors, provided a complete data set for the purposes of the study. In total, the data comprised 125 samples of tutor feedback on five essays per student/tutor pair, and 50 samples of student self-reflective notes. Although there were seven TMAs altogether, TMA05 was omitted from the study because it was based on a team project rather than material related to the course content. The only element of TMA07 included in the study was the student self-reflective notes referring to previous feedback.

Selecting and coding the data

The text of the tutor feedback was interpreted and coded according to the eight content and skills elements, and further differentiated into retrospective and future-oriented feedback (see Table 2). The detailed attributes of the skills categories were developed inductively through working with the samples. The categories of students’ reflective notes were similarly documented. Counting of each category of feedback was conducted at the level of present or absent in each feedback summary. The number of times a tutor made a comment in the same category was not recorded, and seemed less relevant than recording which skills were mentioned and how they were framed. ‘Cases’ were created to map the ‘feedback journey’ of individual students and to determine any relationship between tutor feedback patterns and the student’s reflections.

Findings

With regard to clarity, meaningfulness and navigability of the feedback, there were notable variations in layout, organisation of feedback themes, and sentence composition. Some tutors had separated their retrospective and forward-feeding feedback on the page. In other cases, tutors had combined retrospective and future-oriented feedback into one paragraph or even within sentences. Surprisingly few tutors had actually cross-referenced their summaries to script comments, or signposted their script comments. Despite the great expertise in providing students with useful and constructive feedback, it was also apparent that there was scope at times for increasing the clarity of feedback summaries through improving the structure and by unpacking the jargon. For example, what does it mean if an essay needs ‘more depth’ or a student’s writing is ‘too descriptive’? How can a student replicate ‘good structure;’ next time if a tutor did not explain what exactly was good about the structure last time?

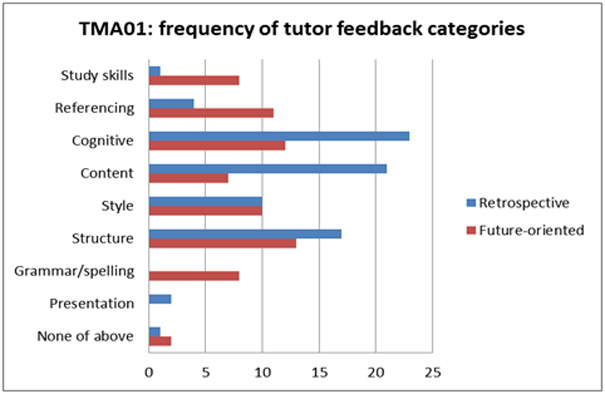

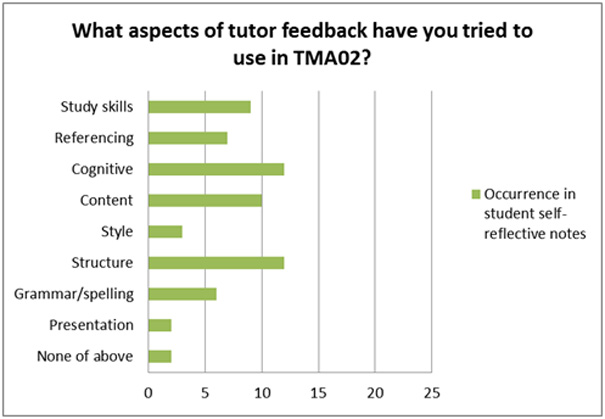

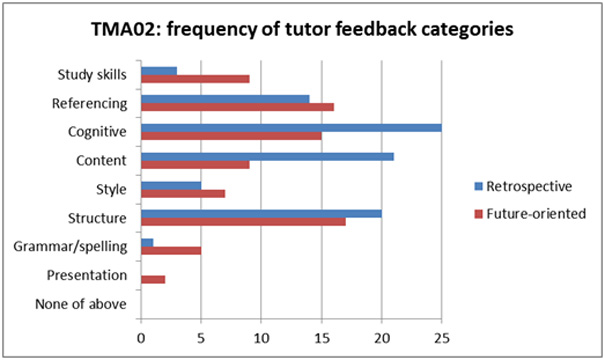

Application of the analytic framework revealed that retrospective tutor feedback mostly outweighed future-oriented feedback, particularly for cognitive skills and content. Tutors paid much more attention to future-oriented feedback in the early parts of the course than in the later TMAs. Student self-reflective notes submitted in TMA02 were generally well matched to the categories in tutor feedback on TMA01, as shown in the cohort charts in figures 1 and 2 and in the individual ‘cases’ represented in figures 6-9.

Figure 1. Number of tutors (max 25) referring to the analytic categories in TMA01 feedback

Figure 2. Number of students (max 25) referring to the analytic categories following TMA01 feedback

Figure 3. Number of tutors (max 25) referring to the analytic categories in TMA02 feedback

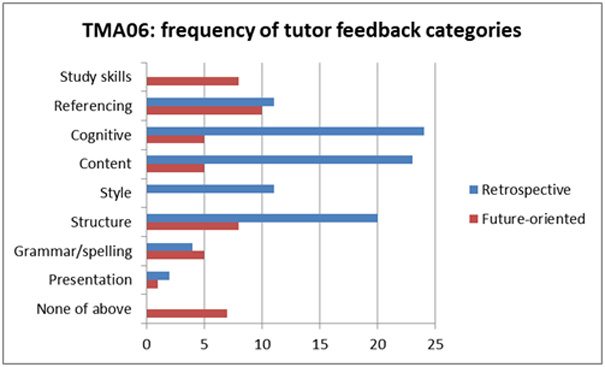

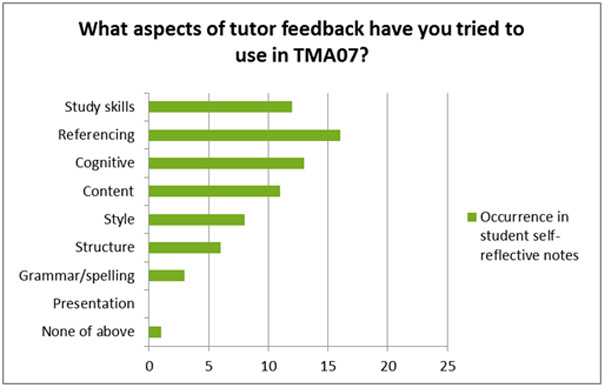

Figure 4 shows the contrasting patterns of feedback for the penultimate TMA. Future-oriented feedback was much reduced at this point and was completely absent in seven cases. At the end of the course, the most popular category reflected back by students was referencing, closely followed by study skills and cognitive skills (see Figure 5).

Figure 4. Number of tutors (max 25) referring to the analytic categories in TMA06 feedback

Figure 5. Number of students (max 25) referring to the analytic categories in TMA07

Overall, the tutors appeared more inclined to give future-oriented feedback on referencing, study skills and essay structure. Content and cognitive skills, which are perhaps more heavily dependent on context, were less likely to be framed as points for future work than as retrospective justifications for the marks given. The following examples of ‘cases’ show differing patterns of tutor feedback and student responses in their self-reflective notes. They indicate the range of feedback patterns observed in the sample through plotting the categories of feedback observed in individual student-tutor pairs.

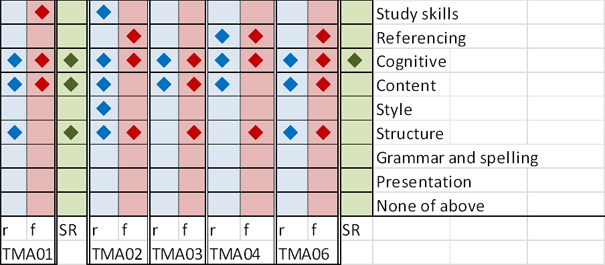

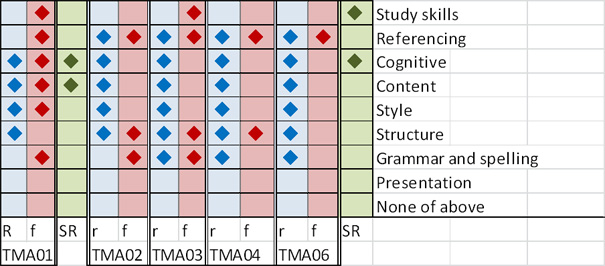

Figure 6. Student whose writing did not progress smoothly, yet who seemed to recognise the paramount need to develop cognitive skills (r = retrospective tutor feedback; f = future-oriented feedback; SR = student self-reflective notes after TMA01 and 06)

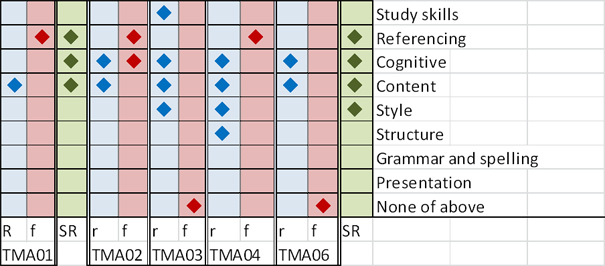

Figure 7. Student who made good progress and seemed responsive to retrospective feedback on content and skills (r = retrospective tutor feedback; f = future-oriented feedback; SR = student self-reflective notes after TMA01 and 06)

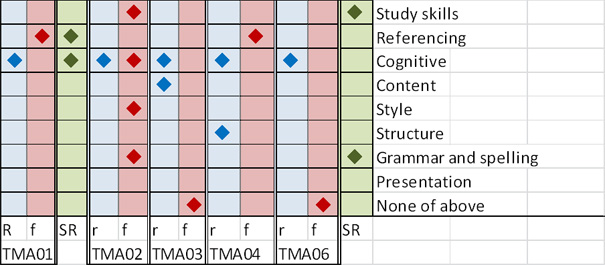

Figure 8. Very selective tutor feedback, where a student reflects superficial engagement with writing in TMA07, despite early engagement with cognitive skills (r = retrospective tutor feedback; f = future-oriented feedback; SR = student self-reflective notes after TMA01 and 06)

Figure 9. Very systematic feedback justifying the marks and focused mainly on referencing, structure and grammar in future-oriented feedback (r = retrospective tutor feedback; f = future-oriented feedback; SR = student self-reflective notes after TMA01 and 06)

The four sample cases shown here demonstrate a range of patterns within tutor-student pairs, and indicate a range of tutor practices. Qualitative engagement with the tutor feedback samples has reinforced this impression of variability and prompted an effort to introduce some practical measures to facilitate a more consistent approach. Personal impressions included concerns that lack of structure, use of jargon, or too much information (even if based on sound judgements about the essay) could be confusing, overwhelming or demotivating. It seemed judicious to offer tutors further guidance on how to develop more future-oriented feedback (Robinson, Pope & Holyoak, 2013), even though retrospective feedback also appeared to have a future-altering impact in some cases (see Figure 7, for example).

Stage 2: developing a tutor feedback guide

A feedback guide, which focused on the tutor’s feedback summary, was developed following the analysis of tutor feedback and the corresponding student self-reflective notes reported here. A list of ten principles was proposed, driven by a desire to meet three outcomes for students: to understand the rationale for their marks, to know what to work on next time and how to do it, to feel motivated to take control of and continue their studies. This closely reflected Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick’s (2006) principles of good feedback practice. Space on the feedback forms was premium, and tutors were requested to steer away from complicated sentence padding such as ‘You do need to focus on ensuring that...’. The guide also specified a consistent structure and urged tutors to double-check their own spelling and sentence construction. The recommended feedback sequence comprised motivational opening, retrospective feedback on strengths, retrospective feedback on weaknesses, and future-oriented feedback on how to develop skills in future work. The detailed attributes of the skills categories, which were developed inductively through working with the feedback samples discussed in Stage 1, informed the organisation and specific content of the guidance.

Principles – The feedback summary should:

- Be clearly structured, and written in clear, simple language.

- Contain a prominent motivational element.

- Be appropriate for the stage of the student journey.

- Be meaningful to each individual student.

- Signpost to script comments where appropriate.

- Include ‘retrospective’ feedback on the submitted work: strengths and weaknesses.

- Include ‘future-oriented’ feedback.

- Provide feedback on both content and skills.

- Flag appropriate events and/or resources.

- Make the implications clear if a student is failing.

The bulk of the document featured examples of wording for the feedback summary, for example, ‘you showed your understanding of the question partly by defining the important terms’ (cognitive skill), or ‘You achieved a good balance in length/word count between the different elements of your answer’ (structure). Future-oriented feedback included: ‘Try to adopt a more formal writing style, by bringing in more of the specialist language and the concepts discussed in the module’ (style), and ‘When you plan your essay, try linking some K101 source material (e.g. video, a resource, or discussion in the Block) to each part’ (content).

The tool was piloted in 2013/14 and feedback gathered from ten tutor volunteers. All pilot tutors enthusiastically embraced the principles and adjusted their feedback practice to varying degrees. Participants were asked to fill in a questionnaire and return it after they had marked the final TMA. Table 3 displays the questions posed and representative tutor comments. Salient issues arising out of the pilot included layout of the document, the degree to which the feedback suggestions should go beyond phrasing for writing skills to suggesting motivational openings/closures and links from strengths to weaknesses, and the degree to which the suggested structure and phrasing should be formally adopted or remain as a staff development aid.

Table 3: Tutor participant responses to the pilot questionnaire

Please comment on the scope and content of the guidance. Is there anything you would change, add or remove? Is there anything you particularly liked or disliked? |

Phrases and sentences that are quite relevant and focused on performance so that feedback can be made very tailored to students as individuals. I liked this. It was good to have some examples of phrases that could be used in feedback, particularly when commenting on TMAs in lower grade bands, as it can sometimes be difficult to think of supportive phrasing! It would be helpful to have a few suggestions on how to move from the strengths paragraph to the opening of the weakness paragraph. |

Please comment on how the tool is presented. Would an alternative format work better? |

I think it is fine but would make it easier to follow by using better layout. Actual content was very helpful. |

Is the style suitable for a K101 Associate Lecturer audience? |

Yes I think it is pitched at the right level and encompasses the knowledge, understanding, core values and skills that I have found in the module so far. |

How easy was it to apply the guidance? |

Very, I’m using it on my next cohort too It would be good to have some help with feedback to students who are consistently unable to take feedback on board. I did not find it that easy to adapt from my previous style in TMA 1 and TMA 2, however along with the pilot guidance careful reading of the marking guidance was very helpful and TMA 3 was the changing point and by TMA 4 I had found the style and pitch easier to put into practice. I occasionally found it difficult to address all aspects of feedback for individual students (i.e. structure, clarity etc) as I didn’t want the negative paragraph to look quite so long and detailed in comparison to the positive one. I therefore selected a couple of points to comment on in this paragraph, which occasionally meant I felt that the justification for the grade wasn’t quite so obvious. |

To what extent does it represent a change to your usual practice? |

It is a much more structured format than I used to use I identified where I was using phrases that included reference to style or structure without properly explaining what this was Quite a big change. My usual practice was to provide feedback on the introduction; main body; and conclusion of the student’s essay. |

Is there anything in your students’ work or communications with you to suggest the impact your feedback has had? Do you think this is at all associated with your use of the tool? |

I was quite heartened and humbled to see that quite a few students actually put my advice and supportive comments into action. I credit this to clear guidance and I was helped to supply this by using the tool. |

Has your monitor identified any issues associated with the use of the tool? |

I noted that she was using the same phrases from the tool and I think she was influenced by the tool in balancing the feedback. |

Discussion

Students value feedback that is clear and has future applicability (Price et al., 2010), and such clarity should benefit students of all abilities. The investigation reported here has indicated that even within a system that has a reputation for excellent feedback practices, it is possible to identify areas for improvement, with these two qualities in mind. This is the first time that the tutor feedback summaries have been systematically analysed according to their specific skill or content focus and their retrospective and future orientations, although there have been similar investigations of written tutor feedback in distance learning (Chetwynd & Dobbyn, 2011; Fernández-Toro, Truman & Walker, 2012). It should be emphasised that the feedback summaries were not the only source of information for students, and some student comments may have been in response to tutor or peer input beyond the TMA feedback summaries. A limitation of this study is that it was unable to take account of all sources of feedback available to the students, and that Stage 1 relied solely on naturally occurring data rather than engaging directly with the individuals concerned, which would have supplied further insights.

The analytic framework developed from Chetwynd and Dobbin’s (2011) original work seemed well suited to the task and to the writing skills focus that prevailed in K101. One of the most difficult aspects of the content analysis was in determining whether an element of feedback was focusing on content or cognitive skills. In the framework, cognitive skills were defined as ‘ways of handling content’, and tutors quite often combined their feedback on content and cognitive skills. This difficulty was usually resolved by determining the actual focus – was it about the inclusion of particular content, or how the student engaged with it, or both? This natural coupling of cognitive skills and content often meant that they were mentioned together in a sentence.

Longitudinally mapping the relationship between tutor feedback and student’s responses to the feedback documented in their self-reflective notes, revealed a range of patterns. The trend in diminishing future-oriented feedback over the course is interesting, although it is difficult to determine its significance without further investigation. Tuck (2012) reported that tutors could be disheartened by seemingly fruitless efforts to create dialogues with students in the marking process, especially when tutors believed that students were only really interested in their grades. According to Tuck, tutors would adopt divergent strategies in response to poor student response, from writing more feedback to resorting to a more superficial, sketchier engagement. The lower level of future-oriented feedback towards the end of the course could also simply be a feature of high energy levels at the beginning when tutors invest early effort to instil good writing practices in their students.

It is possible that students with a highly internalised locus of control may be better able to respond to retrospective feedback in the absence of future-oriented feedback, as they tend to be less reliant on a tutor in bridging the gap between their current performance and their desired goals (Fernández-Toro & Hurd, 2014). Further research into this relationship between locus of control and feedback responsivity would be valuable. A better understanding of the relationship between personal characteristics and student engagement with educational feedback could enable further tailoring of feedback to individuals.

The intended purpose of the feedback guide in this study was to facilitate clarity and meaningfulness. It can be argued that opening up the language can facilitate dialogue, which is highly desirable for feedback to be effective (Nicol, 2010). If students are unable to interpret usefully the written feedback they receive, they will be unable to act on it productively (Carless, 2006; Sadler, 2010). Clarity of language and meaning is also important amongst academics during conversations about students’ written work, if we are to achieve common understanding of a ‘well written essay’. Bailey and Garner (2010) warn that standardised institutional proformas can lead to unhelpfully formulaic approaches to feedback. One of the challenges is to find a balance between proformas that depersonalise feedback relationships and structured guidance that liberates academics and students from unhelpful jargon.

Conclusion

As an evaluation of the observable relationship between tutor feedback summaries on student essays and student responses to the self-reflective questions, the study succeeded in identifying patterns and trends in retrospective and future-oriented feedback, and content and skills feedback. Although the necessary resources were not available at the time, the study would have been greatly enhanced if the individual students and tutors were asked to share their personal experiences of the processes of giving, receiving, and responding to the feedback studied here. Widening the scope of the study to include other sources of feedback would also have been informative.

Development of the analytic framework proved to be valuable in defining the characteristics of an academic essay and the skills demonstrated within. Qualitative engagement with the actual feedback and the analytic categories led to deeper insights into how language can lack transparency of meaning, especially in cases where ongoing dialogue may not occur. Pressing on in attempts to improve clarity of verbal communications regarding the quality of student writing is especially important with a ‘widening participation’ student body. Moreover, students of all abilities should benefit from clarity in feedback.

The longitudinal perspective provided in Stage 1 of this paper has offered an insight into tutor feedback trends, both as a cohort sample and individual tutor-student pairs. The decline in future-oriented feedback over time is worthy of further investigation, as it may result from tutor fatigue or demotivation if students do not appear to be responding. Also, accepting that future-oriented feedback can be more challenging to write, supportive devices such as the feedback tool discussed in Stage 2 could be part of the solution. As dialogue is clearly an essential mechanism in feedback processes, a tool that unpacks the meaning of academic concepts frequently applied to writing skills is suggested to be an aid in conversations between tutors and students as well as amongst academics.

References

- Andrews, R. (2003). The end of the essay? In Teaching in Higher Education, 8(1), (p. 117).

- Bailey, R. and Garner, M. (2010). Is the feedback in higher education assessment worth the paper it is written on? Teachers’ reflections on their practices. In Teaching in Higher Education, 15(2), (pp. 187-198). doi: 10.1080/13562511003620019

- Barnett, R. (2007). A will to learn: Being a student in an age of uncertainty. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Carless, D. (2006). Differing perceptions in the feedback process. In Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), (pp. 219-223).

- Chetwynd, F. and Dobbyn, C. (2011). Assessment, feedback and marking guides in distance education. In Open Learning, 26(1), (pp. 67-78). doi: 10.1080/02680513.2011.538565

- Cramp, A.; Lamond, C.; Coleyshaw, L.; Beck, S. (2012). Empowering or disabling? Emotional reactions to assessment amongst part-time adult students. In Teaching in Higher Education, 17(5), (pp. 509-521). doi: 10.1080/13562517.2012.658563

- Donohue, J. and Coffin, C. (2012). Health and social care professionals entering academia: Using functional linguistics to enhance the learning process. In Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice, 9(1), (pp. 37-60). doi: 10.1558/japl.v9i1.37

- Fernández-Toro, M. and Hurd, S. (2014). A model of factors affecting independent learners’ engagement with feedback on language learning tasks. In Distance Education, 35(1), (pp. 106-125). doi: 10.1080/01587919.2014.891434

- Fernández-Toro, M.; Truman, M. and Walker, M. (2012). Are the principles of effective feedback transferable across disciplines? A comparative study of written assignment feedback in languages and technology. In Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(7), (pp. 816-830). doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.724381

- Gibbs, G. (2010). Does assessment in open learning support students? In Open Learning, 25(2), (pp. 163-166). doi: 10.1080/02680511003787495

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. In Review of Educational Research, 77(1), (pp. 81-112). doi: 10.2307/4624888

- Higgins, R.; Hartley, P. and Skelton, A. (2002). The conscientious consumer: Reconsidering the role of assessment feedback in student learning. In Studies in Higher Education, 27(1), (p. 53).

- Itua, I.; Coffey, M.; Merryweather, D.; Norton, L.; Foxcroft, A. (2014). Exploring barriers and solutions to academic writing: Perspectives from students, higher education and further education tutors. In Journal of Further & Higher Education, 38(3), (pp. 305-326). doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2012.726966

- Knight, P.T. and Yorke, M. (2003). Assessment, learning and employability. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Lizzio, A. and Wilson, K. (2008). Feedback on assessment: Students’ perceptions of quality and effectiveness. In Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(3), (pp. 263-275). doi: 10.1080/02602930701292548

- Molloy, E.; Borrell-Carrió, F. and Epstein, R. (2013). The impact of emotions in feedback. In D. Boud & E. Molloy (eds.), Feedback in higher and professional education: Understanding it and doing it well, (pp. 50-71). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Nicol, D. (2010). From monologue to dialogue: Improving written feedback processes in mass higher education. In Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), (pp. 501-517). doi: 10.1080/02602931003786559

- Nicol, D.J. and Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. In Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), (pp. 199-218). doi: 10.1080/03075070600572090

- Poulos, A. and Mahony, M.J. (2008). Effectiveness of feedback: The students’ perspective. In Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(2), (pp. 143-154). doi: 10.1080/02602930601127869

- Price, M.; Handley, K.; Millar, J.; O’Donovan, B. (2010). Feedback : All that effort, but what is the effect? In Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(3), (pp. 277-289). doi: 10.1080/02602930903541007

- Read, B., Francis, B., & Robson, J. (2005). Gender, ‘bias’, assessment and feedback: Analyzing the written assessment of undergraduate history essays. In Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(3), (pp. 241-260). doi: 10.1080/02602930500063827

- Robinson, S.; Pope, D. and Holyoak, L. (2013). Can we meet their expectations? Experiences and perceptions of feedback in first year undergraduate students. In Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(3), (pp. 260-272). doi: 10.1080/02602938.2011.629291

- Sadler, D.R. (2010). Beyond feedback: Developing student capability in complex appraisal. In Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), (pp. 535-550). doi: 10.1080/02602930903541015

- Scouller, K. (1998). The influence of assessment method on students’ learning approaches: Multiple choice question examination versus assignment essay. In Higher Education, 35(4), (pp. 453-472).

- Tomas, C. (2013). Marking and feedback provision on essay-based coursework: A process perspective. In Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(5), (pp. 611-624). doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.860078

- Tuck, J. (2012). Feedback-giving as social practice: Teachers’ perspectives on feedback as institutional requirement, work and dialogue. In Teaching in Higher Education, 17(2), (pp. 209-221). doi: 10.1080/13562517.2011.611870

- Unistats. (n.d.). The official website for comparing UK higher education course data. Retrieved 22 December, 2014, from http://unistats.com

- Wakefield, C.; Adie, J.; Pitt, E.; Owens, T. (2014). Feeding forward from summative assessment: The essay feedback checklist as a learning tool. In Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(2), (pp. 253-262). doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.822845

- Walker, M. (2009). An investigation into written comments on assignments: Do students find them usable? In Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(1), (pp. 67-78). doi: 10.1080/02602930801895752

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank colleagues in the writing scholarship group in the Faculty of Health & social care and Jim Donohue who provided feedback in the early stages of the project. I am also grateful to my colleague Amanda Greehalgh for initial input into the feedback guide. Additionally, I have to thank the individuals who showed interest in the feedback guide at the EDEN Research Workshop in October 2014. I am grateful to Volker Patent and Jutta Crane for their help with the German translation of the abstract.