Online Support for Online Graduate Students:

Fostering Student Development through

Web-based Discussion and Support

Dr. Martha Cleveland-Innes, [martic@athabascau.ca],

Sarah Gauvreau, [sastesco@hotmail.com],

Athabasca University, Canada

Introduction

Graduate students are participating in online graduate study in increasing numbers (Allen & Seaman, 2007). However, neither the graduate student experience nor the student characteristics are the same for online students as traditional face-to-face students (Cleveland-Innes, Garrison & Kinsel, 2007; Coleman, 2005; Edmonds, 2010; Mullen & Tallent-Runnels, 2006; Song, Singleton, Hill, & Koh, 2004). The opportunity for informal social and academic interaction (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991) that occurs in hallways and graduate student lounges is not readily available to online graduate students. This limitation means that a fulsome graduate student experience may not be readily available online, and must be carefully crafted.

While online graduate students, and their online learning experience, may be distinguishable from graduate students studying face-to-face, they also share the need for specific outcomes of graduate school. One of these outcomes is the development of a professional and scholarly identity as a researcher. Such an outcome is referred to as role-identity formation (Callero, 2003; Collier, 2001). It is plausible that this identity formation occurs, to some extent, during academic courses and formal leaning. However, the Canadian Association for Graduate Studies (CAGS) has identified the need for professionalism through activities which complement discipline-based formal learning (CAGS, 2008). This need, in combination with the unique needs of online graduate students and their required adjustment to online learning environments (Cleveland-Innes & Garrison, 2009), means that support services are of equal or greater importance for online students.

In response to this need, an online, web-based environment was created for students in a Masters program in distance education. The purpose of this support environment was to provide a central virtual location for research students to access resources, information, direction and advice regarding distance education research. This study reports on the student reaction to this web-based support environment.

Background information

The experience of online graduate students has developed ahead of the research required to ensure a fulsome, appropriate graduate student experience is available in these relatively new, virtual education environments. According to Deggs, Grover & Kacirek (2010), online graduate students identified “access, communication, and feedback as essential to maintaining their level of comfort” (p. 697). Students identified timeliness of teacher response as important feeling connected online; “this type of teacher responsiveness is critical not only on assignments but in all aspects of learning engagement” (Cleveland-Innes & Garrison, 2010, p. 12). Fostering a sense of online graduate student community can be enhanced via Web site’s with social networking features, opportunities to meet synchronously via teleconferencing and networking-related events (Exter, Korkmaz, Harlin, & Bichelmeyer, 2009).

Other aspects of the learning engagement normally include activities outside formal program requirements and course activities; informal academic and social interaction and activity. The same high level of support and engagement is required across the range of experiences for online graduate students as those studying face-to-face (Exter, Korkmaz, Harlin, & Bichelmeyer, 2009). Online students hold expectations about this extra-curricular activity and the support that will be available when needed (Deggs, Grover & Kacirek, 2010).

An important part of graduate school, the attitudes and skills associated with scholarly research are central processes and outcomes. An applied program, a central outcome of graduate study in distance education is to prepare some students for the role of practitioner-researcher (Jones & Cleveland-Innes, 2004). Development as a researcher, for graduate students online or face-to-face, requires training and experience; engagement in a socialization process that prepares students to act in the role of researcher is a key aspect of graduate study.

To foster this opportunity, a web-site was designed to increase time spent interacting with faculty and other graduate students to improve socialization opportunities. In this instance, socialization is more than straightforward social time; here socialization is a “process by which people learn the characteristics of their group … (and) the attitudes, values and actions thought appropriate for them” (Kanwar & Swenson, 2000, p. 397). Through this process, students take on new roles and practice the required behaviors and activities of that role. In other words, students to engage in ‘role taking’, the trying of new behaviors exhibited and modeled by others, and ‘role making’, the creation of new behaviors and actions based on new ways of knowing and thinking (Blau & Goodman, 1995).

Given this, graduate education is more than a “simple extension of coursework beyond the bachelor’s degree” (Gullahorn, 2003, p. 204). It requires emotional and social growth along with enhanced cognitive skills. For Van Maanen & Schein (1979), this includes the acquisition of a new socially–based identity and membership in an elite community (Anderson & Swazey, 1998). This is as much so for graduate students online as it is for those in traditional programs, where socialization occurs in the classroom and beyond.

For Gardner (2007), the graduate student experience involves socialization processes in five different areas:

- dealing with ambiguity in program guidelines and expectations;

- balancing graduate school responsibilities with those external to school;

- developing the independence required in the role of scholar;

- understanding the major cognitive, personal, and professional transition that is part of the graduate experience; and

- offering and receiving support needed during this transition.

How can these socialization opportunities be afforded to online graduate students?

This pilot study is a test of one possible answer to this question. The web-based support piloted in this study is to promote “students’ active involvement in the learning and discovery process (through) frequent interaction between faculty and students as well as among students in … informal settings” (Gullahorn, 2003, p. 204). By design, it provides a central virtual location for research students to access resources, information, direction and advice regarding distance education research broadly or the process of designing and implementing research on the topic of distance education and all its sub-fields. The objectives are as follows:

- Provide opportunity for students and faculty to develop a community of inquiry regarding research in distance education.

- Provide a source of advice, information, and encouragement in a moderated environment to student researchers.

- Provide peer interaction opportunities for participants.

- Allow identification and pursuit of special interests by participants.

- Provide students an opportunity to moderate and participate in informal online interaction.

Structure of the web-site

The READS web-site is hosted on an open-source platform called Moodle, a Learning Management System (LMS) used normally to develop and deliver courses. The READS Moodle site is only accessible to those currently registered in programs. The site consists of eight sections in which students can access information. The first section contains an introduction and the objectives to the site. This includes a sound file of Dr. Marti Cleveland-Innes formally introducing visitors to the site, a news forum, a general research discussion forum, a suggested additional resources forum and a welcome forum. The second section of the site incorporates the weekly discussion sessions, where students can engage in asynchronous conversations about topics of distance education and/or research. The third area focuses on research grant opportunities, where updated postings and newsletters for research grants are advertised.

The fourth section is the professors’ corners, where six faculty members maintain their own forums to share their research interests and assist students with similar research goals. The fifth, sixth and seventh sections act as a reference area, subdivided into categories: library & reference information, research ethics and conduct, research societies and journal and online magazines. Each provides links, documents and/or information to each subject.

The final section of the READS site is an area where terminated discussion sessions are situated. These are left open so students can retrieve pertinent information from past dialogues.

Research design

The research question guiding this phase of our research is: Are online graduate students interested in web-based support for extra-curricular activity and discussion with faculty and students? Our argument in support of this question is that extra-curricular activity, online or face-to-face, plays a role in the development of research and scholarly identity and expertise for graduate students.

A mixed methods approach was employed to collect data (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2007). This mixed methods approach, also known as multi-method design, allows for rigorous, methodologically sophisticated investigations. In this investigation, a mix of methods provides the opportunity to measure student activity via numerical counting; this provides a report of what the students actually do through quantitative measures. In addition, mixed methods allow one to ask the students questions that illuminate the numerical count of activity; what benefit does this activity provide and how can we continue and/or improve the activity options to provide further benefit.

The open-source LMS Moodle provides tracking opportunities to measure student activity. Student activity data comes from the reporting functions embedded in Moodle infrastructure. Reports were accessed regularly, and combined for reporting to administrators and the wider academic audience.

Text-based responses to open-ended survey questions represent the qualitative data; the voice of students participating on the site. This data were collected at two points of time over the two year trial; the first occurred four months after the site was opened and the second at the end of year one. Students were asked to reflect and respond regarding three general concepts related to participation on the site: perceived benefits in the activity, interest-level in discussion topics and further requests for online extra-curricular activity.

Findings

READS was first available to graduate students in August 2008 in a program that includes approximately four hundred Masters level students. The site was advertised to students on the main department web-page, and email invitations were sent to all program students. To access the site, a participant has to hold an identification code and password registered with the institution. While program students are the target for the support site, non-program students taking courses in the program also have access to the site.

In the two years since the site was opened, 18,192 viewings of the site were made. Over this time a total of 447 student contributions were made to the site in the form of discussion forum postings or other information items. Figure 1 represents the main page of the site.

The most popular features, as indicated by student traffic, are the Welcome Forum and the Professors’ Corners.

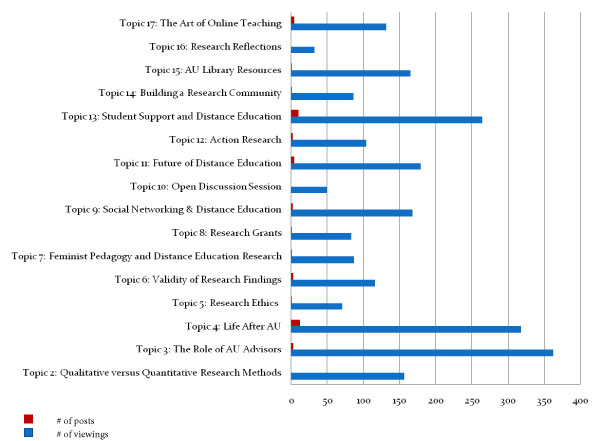

Weekly discussion forums offer graduate students a place to discuss current topics of research. An article, resource and/or introductory post from the site administrator is provided to initiate debate and dialogue. Forum topics are open for one week and then replaced with a new topic, encouraging students to participate in asynchronous communications. Here students could post their thoughts/opinions and reflect/respond to others at their convenience. A variety of topics were discussed with varying amounts of reading and posting. Figure 2 provides a list of topics discussed in the first year of operation, and visually represents the relationship between the number of viewings and number of postings.

Discussion forum activity is made up of more viewing than posting. There is no systematic relationship between viewing and posting but, in general, topics that received highest viewings had more postings. Table 1 provides activity numbers of discussion topics over two years during Fall and Winter semesters. Another noticeable pattern was the variation of activity by day of the week. Mondays were by far the most popular activity day on the site, with as many as 120 viewings per day on Mondays. Activity diminished after Wednesday, with the least amount of site activity on week-ends.

| Topic | Viewings | Number of Postings (excluding those made by admin) | ||

| As of Oct. 10, 2009 | As of February, 20, 2010 | As of April 11, 2010 | ||

Topic 2: Qualitative versus Quantitative Research Methods |

156 | 173 | 179 | 0 |

| 362 | 386 | 398 | 3 | |

| 318 | 345 | 358 | 12 | |

Topic 5: Research Ethics |

71 | 78 | 79 | 1 |

| 116 | 116 | 116 | 3 | |

| 87 | 90 | 92 | 1 | |

| 82 | 89 | 94 | 1 | |

| 168 | 170 | 174 | 2 | |

| 50 | 51 | 51 | 0 | |

| 179 | 181 | 185 | 4 | |

| 104 | 106 | 113 | 2 | |

| 264 | 266 | 268 | 10 | |

| 86 | 86 | 86 | 1 | |

| 165 | 166 | 168 | 1 | |

| 32 | 39 | 39 | 0 | |

Topic 17: The Art of Online Teaching |

71 | 71 | 73 | 5 |

| 131 | 200 | 206 | 4 | |

Topic 19: CDE READS Goes to Florida! |

52 | 58 | 0 | |

Topic 20: Historic Research in Distance Education |

75 | 86 | 2 | |

Topic 21: DE Research Topics to Avoid? |

60 | 73 | 2 | |

Topic 22: The Current State of Research in DE |

66 | 69 | 1 | |

Topic 23: A New Path to DE Research? |

30 | 34 | 0 | |

Topic 24: Review of Distance Education Research |

150 | 155 | 3 | |

Topic 25: Research Interests |

91 | 99 | 5 | |

| 93 | 104 | 4 | ||

Topic 27: Becoming Part of the Research Community |

86 | 91 | 6 | |

Topic 28: Taking the Next Step Towards Research |

84 | 92 | 6 | |

Topic 29: Organising Yourself as a Researcher Part 1 |

60 | 0 | ||

Topic 30: Organising Yourself as a Researcher Part 2 |

50 | 0 | ||

Topic 31: Organising Yourself as a Researcher Part 3 |

89 | 1 | ||

Topic 32: Creating a Research Question Part1 |

93 | 2 | ||

Topic 33: Creating a Research Question Part2 |

54 | 0 | ||

Topic 34: Creating Research Methodology |

58 | 1 | ||

Topic 35: Creating a Dissemination Plan |

26 | 0 | ||

Grand Total: |

2442 | 3400 | 3970 | 78 |

Findings from the collection of qualitative data were analyzed by two researchers. The text data was outlined as 50 complete concepts or ideas. Selective coding centred on the concepts of benefits, or lack of, realized from the site, interest in various aspects of the site and requests for new structures or activities. Coding yielded an inter-rater reliability score of 62%. Table 2 is a summary of the topics distilled from text-based responses, within each conceptual category:

Benefits (23) |

Interaction opportunities Students identified the value of discussing issues with peers, and the creation of documents and resources specific to their needs. The value of peer exchange was emphasized multiple times; “networking and connecting with others” was mentioned often. Interaction benefits span social support and professional development, with references to sharing research ideas with other students and getting advice from experienced researchers. Awareness of and access to valuable scholarship activity Students use the site to identify conferences and publishing opportunities of value. Students share articles and books of perceived value as well. The available information on any subject can be overwhelming. Students use READS to help them determine what valuable and credible information is. Clarification of expectations, responsibilities Questions were raised about expectations and what is acceptable and what is not; knowing the rules of “academic etiquette” was the phrase used. Another said the site makes him/her “feel more comfortable …. returning to school and doing research.” General support The need for, and benefit from, support during graduate school was noted many times. Students want assistance “balancing work, school and home life” and ways to make graduate school enjoyable. |

Interests (16) |

Facilitated discussions Students expressed interest in continued weekly discussions, in relation to research and other issues. Information resources Access to information about funding sources and research design evaluation is of great interest. There is interest in any network, journal, blog, presentation, etc. that relates to the field. Desired information on the following were noted: SecondLife, data analysis software, video, learning motivation, design-based research, teaching presence, publication peer review processes, adult learning, neurobiology and instructional design. |

Requests (11) |

Community boundaries Online interaction is readily available to students on a course by course basis. Thesis students who have finished courses are without this valuable, albeit temporary, community. Students report that READS provides the opportunity to continue this dialogue and ask for increased facilitation to create and sustain community for thesis students. Multiple questions were raised about who can participate and for how long. Looking ahead, students asked if they could continue to participate after the thesis project was complete, and after graduation. It was suggested that discussion formats that are longer than one week would garner more activity and generate more4 in-depth discussion. Description of site activities Students requested clear explanations of the purpose/reason for certain areas of the site. Some referred to the “professors’ corners” and asked for more activity and an understanding of how these areas would operate. |

A few comments noted that some READS discussion replicates course-based discussion.

Discussion

Student interest to the web-based research exploration and discussion site has been notable; high numbers of students are accessing the information and discussions available on the site. However, a small proportion of those visiting the site were motivated to interact with others. The population of students who are posting is uncharacteristic and dynamic; a few of the same students are posting but otherwise the group who posts is unique. In other words, a cohort of students within an integral community is not forming around the site.

This might give one the sense that this is not of interest to the students, and the idea of connecting to such an informal community is of little importance. However, the Welcome Forum on the site has the greatest number of viewings (n=1460) and the greatest number of posts (n=113). Students are willing to come to the site and make themselves known to others. This keen interest then dissipates; the next highest number of postings is 12, to the Life after University discussion forum, with 318 views.

None of the discussion topics generated a rousing discussion. Of 35 discussion topics over two years, nine topics had no postings and views from mid-30s to 60. There was one exception to this pattern. The topic “Qualitative versus Quantitative Research Methods” had 179 views but no posts. It is likely that, in this case, a failure to post had to do with confidence issues rather than lack of interest. In cases where there were relatively few views and no posts we assume limited interest, but acknowledge that these topics at times landed in weeks where academic activity may have taken precedence.

In the survey, some students pointed out that some of the topics READS covers are also discussed in their courses, therefore it is redundant and they don’t participate. Furthermore, with many courses having a participation mark of 10%, many students concentrate in participating in their course forums, where they receive marks, rather than an external site.

Student feedback from survey data identified numerous benefits and keen interest. A more active site with discussion on student experiences as well as research topics was requested by participants. Many topics of interest were suggested on both personal and professional issues. Multiple students spoke of the value of the site and some listed various benefits.

Conclusions

The web-based support site for online graduate students has offered online students increased opportunity to develop as a student and a researcher. It provides increased engagement and connections to other developing research students and faculty researchers; support requested and required online (Cleveland-Innes & Garrison, 2010; Deggs, Grover & Kariek, 2010; Jones, 2009) However, the two-way interaction identified as so critical in web-based distance education (Gunawardena & Mclsaac, 2004) may be less critical than attention and validation. The opportunity to read what we were suggesting students do was of significant value to many, as evidenced in the thousands of hits on the site from a group of approximately four hundred students.

Findings in this study suggest that there is great interest in the information provided but less in participating in discussions. This lack of student postings was noticed by respondents. This issue may have a recursive effect; increased student activity will feed on itself and postings may increase exponentially.

Most remarkable is the number of viewings to the site. In a program with approximately four hundred students at any one point in time, 18,192 viewings of the site demonstrates significant interest in such web-based support. Students provided some postings and some of the resource material available on the site. This is a demonstrable case of peer construction. Timing and topic interest, as indicated by number of viewings, had an effect on student participation. While still in its pilot phase, the site is generating enough participation to warrant continuing the site, with some changes.

The most notable evidence is the interest in non-research related topics regarding the graduate student experience. This does not refute our concept of role-identity formation in graduate school, but supports it. A need for support in multiple areas can be attributed to adjustments made during graduate school; adjustments that may provide for new ways of acting, coping and knowing about oneself and one’s place or role in a field of study.

Role-identity formation evidence can be extrapolated from many comments and the types of interests identified. While students did not refer specifically to an evolving sense of identity, this is reflected in comments made, particularly regarding the benefits offered on the site and requests for further information and interaction. This preliminary assessment provides enough evidence to move to a second phase of the research, and evaluate role identity formation in longitudinal studies of READS participants.

There is a relationship between number of viewings and number of postings. As a general rule, topics that generated the greatest number of viewings also produced more postings. This is true of all topics with a few exceptions. For example, the topic regarding student faculty advisors garnered more viewings than most others but generated only 3 postings. A key finding is the interest among students to discuss topics of general interest – outside of the issue of research activity. Issues that are problem-based and of general interest to all students generated more activity than those focused on questions about research. This is in keeping with findings that suggest that online graduate students expect and respond to support in relation to the broader graduate student experience Graduate student development and skill building will complement discipline-based learning and are seen as “behaviours that can be learned, improved upon with practice, require reflection and benefit from on-going coaching” (Canadian Association of Graduate Study, 2008, p. 1). Our web-site is designed to offer this opportunity for online graduate students, particularly in the area of research skill and researcher identity, in parallel with academic program knowledge.

In sum, we set-out to support research skill and knowledge development, and thus role identity formation as a scholar and researcher, for graduate students in an online distance education Master's degree. The lack of postings on topics regarding research may be an indicator of developing identity; students do not have the confidence to discuss research with peers. It may be that students were looking for the support required by all graduate students on general student issues, as suggested in other research findings. Participation patterns and interviews with students posting to the site suggest that, while interests vary widely, students are looking for general support around usual student issues: relationships with faculty, career choices, access to financial and other student supports, academic resources and library information. Revisions to our web-based discussions will now include a more complex mix of topics related to graduate studies, as expected in historical and still more common face-to-face experiences, and the online learning environment.

References

- Allen, E. & Seaman, J. (2007). Online nation. Five years of growth in online learning. New York, N.Y.: The Sloan Consortium.

- Anderson, M.S. & Swazey, J.P. (1998). Reflections on the graduate student experience: An overview. In M.S. Anderson (editor), The experience of being in graduate school: An exploration. San Francisco, CA.: Jossey–Bass, pp. 3–14.

- Blau, J. & Goodman, N., eds. (1995). Social roles & social institutions. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Callero, P. L. (2003). The sociology of the self. Annual Review of Sociology, (29), 115-133.

- Canadian Association for Graduate Studies, (November, 2008). Professional Skills Development for Graduate Students. Retrieved from http://www.cags.ca/media/docs/cags-publication/Prof%20Skills%20Dev%20for%20Grad%20Stud%20%20Final%2008%2011%2005.pdf

- Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, R. (2010). Higher education and post-industrial society: New ideas about teaching, learning, and technology. In AECT 2010 proceedings. New York, N.Y.: Springer.

- Cleveland-Innes, M. & Garrison, D.R. (2009). The role of learner in an online community of inquiry: Instructor support for first time online learners. In N. Karacapilidis (editor), Solutions and innovations in web-based technologies for augmented learning: Improved platforms, tools and applications. p. 167-184. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

- Cleveland-Innes, M.; Garrison, R. & Kinsel, E. (2007). Role adjustment for learners in an online community of inquiry: Identifying the needs of novice online learners. International Journal of Web-based Learning and Teaching Technologies, 2(1), (pp. 1-16)

- Coleman, S. (2005). Compelling arguments for attending a cyber classroom: Why do students like online learning? Retrieved from http://www.worldwidelearn.com/education-articles/benefits-of-online-learning.htm

- Collier, P. (2001). A differentiated model of role identity acquisition. Symbolic Interactionist, 24(2), (pp. 217-235)

- Creswell, J. & Plano-Clark, V. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

- Deggs, D.; Grover, K. & Kacirek, K. (2010). Expectations of adult graduate students in an online degree program. College Student Journal, 44(3), (pp. 690-699)

- Edmond, K. (2010). Discovering the needs of online graduate students: A doctoral research study. Paper presented at the Canadian Society for the Study of Higher Education conference, Ottawa, Ontario.

- Exter, M.E.; Korkmaz, N.; Harlin, N.M. & Bichelmeyer, B.A. (2009). Sense of community within a fully online program: Perspectives of graduate students. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 10(2), (pp. 177-194)

- Gardner, S. (2007). “I heard it through the grapevine”: Doctoral student socialization in chemistry and history. Higher Education, 54(5), 723-740, DOI: 10.1007/s10734-006-9020-x

- Gullahorn, J. (2003). Graduate study. In A. DiStefano, K.E. Rudestam, & R.J. Silverman (editors). Encyclopedia of distributed learning, (pp. 203–207). Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage.

- Gunawardena, C. N. & McIsaac, M. S. (2004). Distance education. In D. H. Jonassen (editor), Handbook of research for educational communication and technology (2nd ed., pp. 355-396). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Jones, W.P.L. (2009). Distance education in the digital age: College students in virtual academic programs. (Doctoral disseration). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database. (3383846).

- Jones, T. & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2004). Considerations for the instruction of research methodologies in graduate level distance education degree programs. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 5(2). Retrieved from http://tojde.anadolu.edu.tr/tojde14/index.htm

- Kanwar, M. & Swenson, D. (2000). Canadian Sociology. Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

- Mullen, G. & Tallent-Runnels, M. (2006). Student outcomes and perceptions of instructors' demands and support in online and traditional classrooms. The Internet and Higher Education, 9(4), (pp. 257-266)

- Pascarella, E. & Terenzini, P. (1991). How college effects students. San Francisco, CA.: Jossey-Bass.

- Rourke, L. & Kanuka, H. (2007). Barriers to online critical discourse. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 2, (pp. 105–126)

- Song, L.; Singleton, E. S.; Hill, J. R. & Koh, M. H. (2004). Improving online learning: Student perceptions of useful and challenging characteristics. Internet and Higher Education, 7, (pp. 59-70)

- Van Maanen, J. & Schein, E.H. (1979). Toward

of theory of organizational socialization. Research in Organizational

Behavior, 1, (pp. 209-264)