Reconsidering Moore's Transactional Distance Theory

Yiannis Giossos [ygiosos@ath.forthnet.gr]

52, Andromachis St.,

17671 Kallithea,

Athens, Greece

Maria Koutsouba [makouba@phed.uoa.gr]

Antonis Lionarakis [alionar@otenet.gr]

Kosmas Skavantzos

Hellenic Open University [http://www.eap.gr]

18, Parodos Aristotelous St.,

26 335, Patra, Greece

Abstracts

English

One of the core theories of distance education is Michael Graham Moore's Theory of Transactional Distance that provides the broad framework of the pedagogy of distance education and allows the generation of almost infinite number of hypotheses for research. However, the review of the existing studies relating to the theory showed the use of a variety of functional definitions of transactional distance that reveals an absence of consensus. The purpose of the present study is the theoretical processing of its fundamental concept "transactional distance", as well as the incorporation of the theory into the epistemological framework of realism. In particular, the absence of consensus is overcome through the work of John Dewey. On this basis, transactional distance was defined as "the distance in understanding between teacher and learner". Additionally, an attempt is made to position the Theory of Transactional Distance in the epistemological framework of realism. From this point of view, transactional distance is one of the results of teaching.

Greek

Μία από τις κύριες θεωρίες της εξ αποστάσεως εκπαίδευσης, είναι η θεωρία της "διαδραστικής απόστασης" του MichaelGrahamMoore. Η συγκεκριμένη θεωρία, έχει αποτελέσει ένα δημιουργικό παιδαγωγικό πλαίσιο για την εφαρμογή της εξ αποστάσεως εκπαίδευσης, ενώ παράλληλα, έχει επιτρέψει την διατύπωση ενός μεγάλου αριθμού ερευνητικών υποθέσεων. Παρόλα αυτά, μέσα από την επισκόπηση των ερευνών, παρουσιάζεται ποικιλία διαφορετικών λειτουργικών ορισμών της "διαδραστικής απόστασης", η οποία αναδεικνύει απουσία συναίνεσης σχετικά με αυτήν. Σκοπός λοιπόν της παρούσας μελέτης, ήταν η θεωρητική επανεξέταση της έννοιας της "διαδραστικής απόστασης" και η ένταξη της στο επιστημολογικό πλαίσιο του "ρεαλισμού ". Ειδικότερα η απουσία συναίνεσης σχετικά με τον λειτουργικό ορισμό της "διαδραστικής απόστασης" μπορεί να ξεπερασθεί με την συνδρομή του έργου του JohnDewey. Στην βάση αυτού, η "διαδραστική απόσταση" ορίσθηκε ως "η απόσταση κατανόησης μεταξύ διδάσκοντα και μαθητευόμενου ". Εντάσσοντας δε την θεωρία στο επιστημολογικό πλαίσιο του "ρεαλισμού", η "διαδραστική απόσταση" προσεγγίζεται ως αποτέλεσμα της διδακτικής διαδικασίας.

Keywords

transactional distance, distance education, realism.

Introduction

The first attempts at the creation of theoretical approaches in the field of distance learning started in the 1950s (Keegan, 2000: 81). As characteristically pointed out by Holmberg at the end of the 1980s, theoretical approaches provide the potential for hypotheses concerning (i) what one can expect from distance learning, (ii) under what conditions and circumstances and (iii) through which practices and procedures (Simonson, Schlosser and Hanson, 1999: 1). Keegan classifies the developed theories in four groups. The first includes the theories of independence and autonomy, the second the theory of industrialization of teaching, the third the theories of interaction and communication and finally, while the fourth aims at explaining distance learning through a combination of the theories of communication with the philosophy of education (Keegan, 2000).

One of these theories is the Theory of Transactional Distance by Michael Graham Moore that provides the broad framework of the pedagogy of distance education, allows the generation of almost infinite number of hypotheses for research (Moore, 1990a) and resulted in "a typology of all educational programs having [as a] distinguishing characteristic of separation of learner and teacher" (Keegan, 2000). Since then, several researchers focused their efforts to confirm Moore's theoretical model through empirical research. However, the results of these efforts were controversial (Gorsky & Caspi, 2005). Yet, the Theory of Transactional Distance is one of the core theories in the field and the theoretical discussion about it is valuable. Thus, the purpose of the present study is the continuation of the theoretical processing of the fundamental concepts of the Theory of Transactional Distance and its incorporation into the epistemological framework of realism.

Moore's Theory of Transactional Distance

Since the beginning of the 1970s, Moore had started elaborating on elements of his theory. Characteristically, in 1972, Moore distinguishes two primary concepts pertaining to distance learning: distance teaching and learner autonomy (Moore, 1972). Although these two concepts are included in the later theory of transactional distance, the term 'transactional distance' is not employed at this early stage. Moore first used the term and idea of 'transactional distance' at the beginning of the 1980s. As the writer admits, the idea of 'transaction' was borrowed from the American philosopher John Dewey (Moore, 1993a), whose influence on Moore's work was manifold. However the rationale of the Theory of Transactional Distance emerged from an analysis of a large selection of program descriptions and of the literature and was based on Wedemeyer's work (Saba, 2003).

The first reference to the idea of transactional distance was made by Moore in one of his books where he points out that in independent studies (a term used in those days to refer to distance learning programmes) one observes a separation and a space between the teacher and the learner in the context of the study programme (Boyd & Apps, 1980). Moore names this distance transactional distance. The term does not refer to the geographical distance between the teacher and the learner but to the development (or not) of a transaction, in other words, the development of a particular form of interaction between teacher and learner because of their geographical separation. In the following years, Moore and his associates further elaborated the theory (Moore, 1990b; 1993; Moore & Kearsley, 1996). In particular, the content of the term "transactional distance" was determined with more definition and accuracy, while the Theory of Transactional Distance was elaborated and developed by Farhad Saba and Rick L. Shearer (1994), Yau-Jane Chen and Fern K. Willits (1998), Yau-Jane Chen (2001a; 2001b), Karen Lemone (2005) and Sushita Gokool-Ramdoo (2008). In its complete form, the theory appears in 1993 (Moore, 1993).

One of the principles of the theory is that the particularities of space and time pertaining to teacher and learner which characterize distance learning, despite the fact that there are multiple and ever changing learning contexts of distance education (Chen, 2001a), create: (i) particular behavioural models for the teacher and the learner, (ii) psychological and communication distance between them and (iii) insufficient understanding of each other. On this basis, Moore defines as transactional distance "the psychological and communication space" between the learner and the teacher: «It is this psychological and communication space that is the transactional distance» (Moore, 1993: 22). According to Moore, the development of the transaction is influenced by three basic factors: (i) the dialogue developed between teacher and learner, (ii) the structure that refers to the degree of structural flexibility of the programme and iii) the autonomy that alludes to the extent to which the learner exerts control over learning procedures.

Specifically, dialogue, in this case, is something more than mere communication and interaction between learner and teacher. In particular, this type of communication occurs within the context of clearly defined education targets, cooperation and understanding on the part of the teacher and, ultimately, culminates in solving the learner's problems. Obviously, Moore perceives dialogue as an element connected with the quality of communication rather than the frequency. Therefore, the objective is the quality and nature of the dialogue and not its frequency. Structure is approached by Moore from the perspective of course's rigidity (Zhang, 2003) or flexibility in terms of: (i) establishing educational goals of the course, (ii) teaching techniques employed by the course, (iii) assessment procedures and, finally, (iv) the extent to which individual needs are covered. It becomes obvious again that Moore perceives structure as a qualitative feature rather than quantitative. Finally, Moore defines autonomy as the extent to which the learner exerts control over learning procedures. Autonomy, in other words, is the degree of decision the learner has over issues such as educational goals, manner of teaching followed, rate of progress and methods of assessment.

Based on the above, Moore assumes that: (i) transactional distance and dialogue are in inverse proportion to each other, meaning that any increase in either leads to decrease of the other. (ii) Increase in course structure leads to reduction of dialogue and, consequently, increase in transactional distance. However, limitations are imposed on the reverse direction; reduction in structure does not result in increase in dialogue and, consequently, reduction of transactional distance throughout the whole spectrum. Moore stresses that if structure drops below a threshold, transactional distance increases. It should be noted here that Moore does not specify which this structure threshold is, under which transactional distance increases. (iii) Transactional distance and autonomy are proportional to each other, as increases or decreases in the one result in corresponding increases or decreases in the other (McIsaac, & Gunawardena, 1996; Giossos , Mauroidis, Koutsouba, 2008).

At this point it should be noted that after the appearance of the Theory of Transactional Distance a number of studies were carried out in an attempt to examine it empirically. In particular, there are eleven research studies (Bischoff 1993; Bischoff, Bisconer, Kooker, & Woods, 1996; Saba, 1988; Saba and Shearer, 1994; Chen 2001a, 2001b; Chen and Willits, 1998; Force, 2004) focused on a number of questions relating to Moore's theory affirming that the theory is a tool for analysis of practice (Garrison, 2000) and for generating questions for empirical testing (Moore, 1990). However, according to Gorsky & Caspi (2005) the results of these studies were controversial due to a tautology issue that emerged from the variety of functional definitions of transactional distance and dialogue that these studies used (Gorsky & Caspi, 2005). This variety in fact reveals the absence of consensus, an absence that the present study attempts to overcome through the continuation of the theoretical processing of the theory's fundamental concept "transactional distance". In the following section, "transactional distance" is approached through the work of John Dewey.

Reconsidering transactional distance in distance education

Besides philosophy and psychology, John Dewey also delved into education and was the representative of the American progressive movement in education. Dewey used the idea of transaction in quite a number of his works. In one of them, the writer supports that experience is the outcome of some sort of interaction of the individual with the environment (Dewey, 1938). Moreover, this interaction cannot be separated from the environment (or surroundings) in which it occurs. In particular, Dewey states that experience exists, because a transaction takes place between the individual and the surroundings (Dewey, 1938). In order to fully understand this statement, one must resort to a study that Dewey elaborated at a later time with his colleague Arthur Bentley. In this study concerning theories of knowledge within the framework of philosophy of science, Dewey analysed in detail the concept of transaction in conjunction with the manner in which the human mind can acquire the knowledge of the world outside the individual (Dewey & Bentley, 1949).

Dewey's position was that all philosophers, from Plato to modern ones, held the fallacy that knowledge is obtained through observation, an erroneous perception that Dewey characteristically referred to as 'spectator theory of knowledge' (Audi, 1999: 239). According to this view, knowledge was treated as a passive response to events, and the truth of these events was verified by the degree to which beliefs for events were in agreement with them. On the basis of this view, thinking about the world lies separately and independently from the world itself. At this point, it should be noted that the distinction between the mind and the world, or, otherwise, between mind and matter (mind-matter/res cogitans- res extensa) was made by Rene Descartes (1596-1650) and influenced western philosophy for a long period (Molivas, 2000).

Dewey expresses different and, to a great extent, opposite view. Particularly, for Dewey there is no distinction between mind and matter. The world is a "moving whole of interacting parts" (Wiberg, 2006:5). The mind constitutes one part of the entity of the world. Experience of the world is acquired through the interaction of man with his surroundings, an interaction which works in two directions: the environment influences the way man perceives it, and the way man perceives the environment influences the latter. In other words, Dewey did not view thinking as a product of human interaction with the environment but as a tool through which man controls and guides this interaction. Dewey refers to this type of interaction concerning knowledge as transaction, because at the time, interaction was defined as a simple relationship of action-reaction, applied only to a mechanistic relationship between entities (animate and inanimate) and which alluded to relationships of cause and result. Thus, the term interaction could not express the deeper process through which knowledge is acquired.

According to this view, knowledge is an activity of constructing concepts. At the same time, knowledge is an adaptive human response to the conditions of the environment that aims at the reconstruction of these conditions through the construction of concepts. Additionally, knowledge does not concern the way things are, but the relationship between actions, such as the construction of concepts, and the consequences of these actions. Concluding, according to Dewey, the use of the idea of transaction requires that man and his environment cannot be viewed independently form one another. Furthermore, the subject cannot be distinguished from the object, the soul from the body, the spirit from the matter, and the self from the other. There can be no ultimate truth or absolute knowledge.

What is the significance of all these for distance learning and, mainly, for the functional definition of transactional distance in distance learning? We have already mentioned that Moore defined transactional distance as "the psychological and communication space" between the learner and the teacher (Moore, 1993: 22). However, based on the aforementioned argument, one could support that transactional distance in distance learning should be defined exclusively as "the distance in understanding between teacher and learner", and not as "the psychological and communication space between the two". The question that rises at this point is to what understanding refers to. Understanding refers to mutual understanding (co-understanding). In the vernacular, the phrase 'you don't understand me' or 'you're not following me' is commonly used to stress the lack of mutual understanding or common perception of ideas, emotions, situations, etc. Transactional distance, therefore, is nothing more than the lack of common or mutual perception of knowledge, thoughts, approaches but also needs (psychological and educational), emotions, etc.

Additionally, transactional distance is something that is experienced and perceived by the people themselves. There is no such thing as an abstract or intangible transactional distance, but a specific individual one. Moreover, transactional distance is experienced and perceived in different ways in different cultural and educational contexts as "individuality and disposition of distance learners differs from one cultural to another cultural setting" (Kawachi, 2003). For example, transactional distance is experienced and perceived differently between Greeks and Indians, or between undergraduate and postgraduate students.

Apart from the attempt to overcome the absence of consensus about the functional definition of "transactional distance" through the work of John Dewey, this theoretical processing also makes an attempt to position the Theory of Transactional Distance in an epistemological framework. Realism has been chosen in this case, for reasons that would be made obvious in the following section.

Towards an epistemological reconsideration of Moore's theory

In the quest of educational research there are various epistemological frameworks such as those of positivism and post-positivism (Gall, Gall & Borg, 2007). Studies following positivism try to verify empirically hypotheses and search for relationships between variables. On the other hand, studies following post-positivism try to interpret procedures instead of explaining relationships between variables. The Theory of Transactional Distance has been studied by a number of researchers in both ways. However, positivist approaches has been criticised both for its assumptions (Benz & Shapiro, 1998) and for the manner of its implementation in social research (Stockman, 1983) and consequently in educational research. As characteristically pointed out by Robson (2002), the quest for steady relationships between two variables is easy in the world of sciences because it is possible to create a controlled environment, a closed system, where these will be isolated. In the real world of humans, this is not feasible. People function in an open system that cannot be controlled. The world of humans, and consequently, that of education, is an open system in which input and output cannot, at any given time, be controlled. In other words, the effort to show a steady relationship between the variables of transactional distance and structure cannot lead to any concrete result. Yet, the search of relationships between variables is still valuable. In an attempt to overcome the problems that positivism faces, the epistemological framework of realism is proposed. But what is realism and how it can be related to Moore's Theory of Transactional Distance?

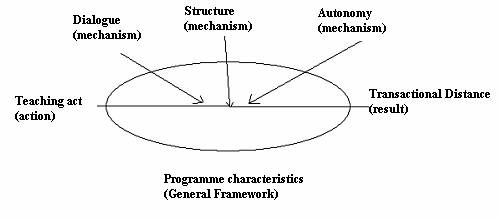

Realism is an epistemological framework that avoids positivism as well as post-positivism (Robson, 2002). In realism, science concerns with the discovery of scientific laws, which are considered to be patterns of an action or mechanism (House, 1991). In particular, according to the realistic view, science investigates actions, which, through mechanisms, produce results under certain conditions (Robson, 2002:32). From this point of view, transactional distance is one of the results of teaching (action) and structure, autonomy and dialogue are mechanisms of transactional distance. A first graphic representation of the above appears in Figure 1

Figure 1. Graphic representation of Moore's theory according to realism

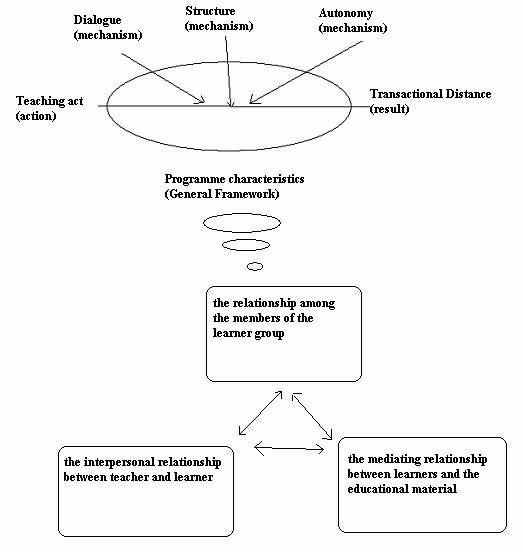

In addition, in order to investigate social systems, realism studies mechanisms at various levels: micro, macro, group, organizational, etc. Thus, in the case of Moore's theory, if transactional distance is defined as "the distance in understanding between teacher and learner", then it must be examined at the level of: (i) the interpersonal relationship between teacher and learner, (ii) the relationship among the members of the learner group, and (iii) the mediating relationship between learners and the educational material. According to this, the Theory of Transactional Distance may be illustrated as in Figure 2:

Figure 2. Final graphic representation of Moore's theory according to realism

Within the context of realism, the objective is to prove the existence of hypothetical mechanisms and not to find predictable regularities. In the case of Moore's theory, the objective is to prove that the mechanisms of structure, dialogue and autonomy actually work at every level. Additionally, the conditions under which these mechanisms are set in motion must be discovered. For instance, in Moore's theory, during the study of the mechanisms the fact that the relationship between learner and teacher occurs within a context of authority should be kept in mind. Similarly, the fact that transactional distance is perceived differently not only on the basis of the cultural and educational contexts of the people experiencing it but also on their socio-economic level should also be taken into consideration (Sayer, 2000:12). Finally, according to realism a phenomenon can be explained, but this does not necessarily means that it can be predicted since in open systems, such as in society and education, the complexity of the involved structures makes prediction impossible.

Conclusion

In the present study, an attempt was made to approach Moore's Theory of Transactional Distance and to discuss the continuation of the theoretical processing of its fundamental concepts as well as to incorporate it into the epistemological framework of realism. In particular, the absence of consensus that emerged from the variety of functional definitions of transactional distance that have been used in a number of studies was attempted to be overcome through the work of John Dewey. On this basis, transactional distance was defined as "the distance in understanding between teacher and learner". Additionally, this theoretical processing also made an attempt to position the Theory of Transactional Distance in an epistemological framework. Realism has been chosen in this case, being an epistemological framework that avoids positivism as well as post-positivism. According to this theory, science investigates actions, which, through mechanisms, produce results under certain conditions. From this point of view, transactional distance is one of the results of teaching (action) and structure, autonomy and dialogue are mechanisms of transactional distance. Thus, in the case of Moore' s theory, if transactional distance is defined as above, then it must be examined at the level of: (i) the interpersonal relationship between teacher and learner, (ii) the relationship among the members of the learner group, and (iii) the mediating relationship between learners and the educational material. As Moore's Theory of Transactional Distance is one of the core theories of distance education, the continuation of its theoretical processing is valuable as well as the verification of this theoretical processing.

References

[1] Audi, R. (1999). The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press.

[2] Benz, V. M. & Shapiro, J. J. (1998). Mindful Inquiry in Social Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications

[3] Bischoff, W. R. (1993). Transactional distance, interactive television, and electronic mail communication in graduate public health and nursing courses: Implications for professional education. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Hawaii.

[4] Bischoff, W. R., Bisconer, S. W., Kooker, B. M., & Woods, L. C. (1996). Transactional distance and interactive television in the distance education of health professionals. American Journal of Distance Education, 10(3), 4-19.

[5] Boyd, R. &. Apps, J. (1980). Redefining the Discipline of Adult Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

[6] Chen, Y. J. (2001a). Transactional distance in World Wide Web learning environments. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 55(4), 327-338.

[7] Chen, Y. J. (2001b). Dimensions of transactional distance in World Wide Web learning environment: A factor analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 459-470.

[8] Chen, Y. J., & Willits, F. K. (1998). A path analysis of the concepts in Moore's theory of transactional distance in a videoconferencing learning environment. The American Journal of Distance Education, 13(2), 51-65.

[9] Chen, Y. J., & Willits, F. K. (1998). A path analysis of the concepts in Moore's theory of transactional distance in a videoconferencing learning environment. The American Journal of Distance Education, 13(2), 51-65.

[10] Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Collier Mac Millan Publishers.

[11] Dewey, J. and Bentley, A. F. (1949). Knowing and the Known. Boston: The Beacon Press.

[12] Force, D. (2004). Relationships among transactional distance variables in asynchronous computer conferences: A correlational study. Unpublished Master Thesis, Athabasca University.

[13] Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P. & Borg, W. R. (2007) Educational Research: An Introduction. Boston: Pearson International Edition

[14] Garrison, R. (2000). Theoretical challenges for distance education in the 21st century: A shift from structural to transactional issues. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 1(1), 1–17 available at http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/viewFile/2/22

[15] Giossos, Y. Mauroidis, H. & Koutsouba, M. (2008) Research in distance education: review and perspectives. Open Education - The Journal for Open and Distance Education and Educational Technology 4(1) available at http://www.opennet.gr/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=13&Itemid=28

[16] Gokool-Ramdoo, S. (2008). Beyond the Theoretical Impasse: Extending the applications of Transactional Distance Theory International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 9(3) http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/541

[17] Gorsky, Α. & Caspi A. (2005). A critical analysis of transactional distance. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 6(1), l - 11.

[18] House, E. R. (1991). Realism in research. Educational Researcher, 20: 2-9

[19] Huang, H. M. (2002). Student perceptions in an online mediated environment. International Journal of Instructional Media, 29(4), 405-422.

[20] Kawachi, P. (2003). Support for Collaborative e-Learning in Asia. Asian Journal of Distance Education 1(1), 46-59.[www.AsianJDE.org]

[21] Keegan, D. (2000). Foundations of Distance Education. Athens: Metaixmio.

[22] Lemone, K. (2005). Analysing Cultural Influences on E-Learning Transactional Issues. In G. Richards (Ed.), Proceedings of World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education 2005 (pp. 2637-2644). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

[23] McIsaac, M.S. & Gunawardena, C.N. (1996). Distance Education. In D.H. Jonassen, ed. Handbook of research for educational communications and technology: a project of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology. (pp. 403-437). New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan

[24] Molivas, G. (2000). PhilosophyinEurope: The age of enlightenment, Patra: Hellenic Open University.

[25] Moore, M. G. & Kearsley, G. (1996). Distance Education: A systems view. New York: Wadsworth.

[26] Moore, M. G. (1972). The second dimension of independent learning. Convergence 5: 76-88.

[27] Moore, M. G. (1990a). Background and overview of contemporary American distance education. In M. Moore (Ed.), Contemporary issues in American distance education (pp. 12-26). New York: Pergamon.

[28] Moore, M. G. (1990b). Recent contributions to the theory of distance education, Open Learning, 5(3), 10–15.

[29] Moore, M. G. (1993). Theory of transactional distance. In D. Keegan (Ed.), Theoretical principles of distance education (pp. 22-38). New York: Routledge.

[30] Robson, C. (2002). Real World Research (2nd ed) Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell Ltd.

[31] Saba, F. & Shearer, R. (1994). Verifying key theoretical concepts in a dynamic model of distance education. The American Journal of Distance Education 9(1), 36-59.

[32] Saba, F. (1988). Integrated telecommunication systems and instructional transaction. The American Journal of Distance Education 2(3), 17-24.

[33] Saba, F. (2003). Distance Education Theory, Methodology and Epistemology: A Pragmatic Paradigm In M. G. Moore & W. Anderson (Eds.), Handbook of Distance Education (pp. 3-20). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

[34] Sayer, A. (2000). Realism and Social Science. London: Sage

[35] Simonson, M., Schlosser, C. & Hanson, D. (1999). Theory and Distance Education: A New Discussion, The American Journal of Distance Education 13(1), available at http://www.uni-oldenburg.de/zef/cde/found/simons99.htm.

[36] Stockman, N. (1983). Anti positivism Theories of the Sciences. Dordrecht: Reidel

[37] Wiberg, M. (2006). Freedom as a value of practice in ethical learning, Philosophy and Science Studies 4, available at http://www.think.aau.dk/Publications/philosophy-science/2006/4-freedom-learning.pdf

[38] Zhang, A. (2003). Transactional distance in web-based college learning environments: Toward measurement and theory construction, Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University.