Online Learning: Strategy or Sophistry?

"Don't start from here."

James G Gallagher

"Top managers spend more time and energy on implementing strategies than choosing them. Strategies that are well chosen will fail because of poor implementation. Getting the organisational structures right for a particular strategy is thus critical to practical success."

R. Whittington; What is Strategy and does it matter? P112

Higher education is an industry and one that is currently experiencing the vagaries of a turbulent environment (Quote 1). Where once 'Say's Law' held sway and educational institutions thrived on the basis of predictable funding and student enrolment with little or no competition today, they face an uncertain future where the price of failure could mean closure. They are facing a crisis in both their external and internal environments. Externally they are confronted by massification of education and greater competitive pressures whilst internally they face the dilemma of increasing customer demands, diminishing resources and culture shock. "Although the government has dropped its target of 50 per cent of under 30-year-olds going to university by 2010, it remains committed to "moving towards" that figure" (Boone, 2006).

"Higher education is a mature industry in which there seems likely to be only slow growth in traditional, core markets."

Napier University Strategic Plan 2002-2006

How educational institutional management balances these opposing factors is the crux of survival. These institutions are today the equivalent of any business organisation. They are run on a business philosophy that is closer to market economics than to philanthropic ideals. Where the individual lecturer may hold to the ideals of education as a vocational choice and a right of everyone the institutions view it in terms of cost benefit analysis where resources are finite and competition for customers (students) is fierce and becoming stronger. For the sake of argument a distinction is made here between the terms consumer and customer. When the percentage figure of the population attending university was a single digit students were to a great extent passive consumers of the educational service. Today however, where government "Medium-term funding plans suggest that by 2008, the proportion of young people will rise slightly to about 45.5%."(Boone, 2006) attending university, students are far more aggressive and active in the pursuit of their educational purchases. They have become customers who are more discriminating in their choice of educational institution and mode of learning, and as such are voting with their feet.

Such a turbulent environment calls for institutions to change and adapt to meet these challenges. However, as Milliken, 1990, points out change for many of these institutions is not easy. Historically, the industry has been characterised by resistance and self-paced incremental change but the new market dynamic requires a faster, more aggressive market orientation.

One recent example of strategy aiming to harness these dynamics is Oxford University who announced - 25th March 2005 - that it would be seeking to increase the percentage of its students from abroad. It needed these high paying (£20,000 +) students to fund the salaries it must offer to attract the highest calibre academics so it could compete with America's Ivy League institutions.

In business in general, for the last quarter century or so, strategy has been viewed through Cartesian eyes, which sees a split between mind and body. Here the mind or "head" represents the creation of the mission, visions, and strategies and plans all of which are future oriented and geared to leading the organisation – the "body" to a more fruitful and secure future.

However, in their work Bartlett and Ghoshal indicate, that organizations are captured in a "strategic trap": "The problem is that their (manager's) companies are organizationally incapable of carrying out the sophisticated strategies they have developed. Over the past 20 years, strategic thinking has far outdistanced organizational capabilities".

"We recognise that we are and will be engaging with an increasingly diverse population of learners. We also recognise the need for greater innovation in curriculum design and assessment methods, and in the nature and utilisation of our infrastructure, to ensure that we support adequately the preferred learning styles of this more varied population of students."

Napier University Strategic Plan 2002-2006

Educational institutions, and in this example the Business School, are potentially facing an organisational trap stemming from the idea that a strategy based on online learning is a cure-all for the ills which confront these institutions, e.g. falling retention rates and cash flow. To some extent this view is augmented by Bonk, 2004 when he observed that, "many universities that fail to keep pace with technological advances will close" He tempered this view by saying that universities will close because of, for example, lower state funding or the inability of university bureaucracies to respond to rapidly-changing student learning demands involving technology. However, no matter what the causal base of institutional closure the dynamics of change appear to be racing ahead of Business School strategy with the result that there tends to emerge a pressure to view technologies such as Web CT as a panacea, providing a convenient, if ill defined basis for emergent strategy (Quote 2).

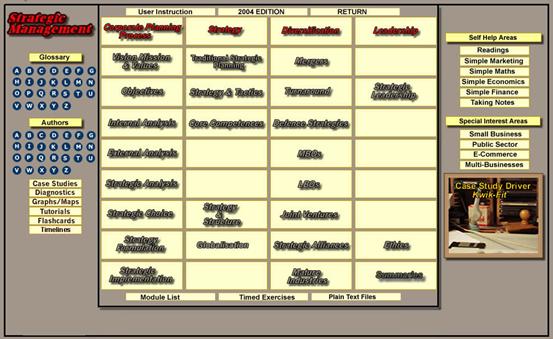

E-learning has been defined as "the use of network technologies to create, foster, deliver, and facilitate learning, anytime and anywhere" (Linezine, 2000). The bedrock of the institution's emergent e-learning strategy, WebCT (Figure 1 and 2 ), rests upon an interface that comprised four elements:

Communication Tools, Content Tools, Evaluation Tools, and Administration. In essence this caters for a coalition of three user groups:

- the student, (the customer and service user)

- the lecturer and (pedagogic provider)

- the institution, (administrative: communication and control)

each of whom has both a shared agenda and a unique one. Failing to appreciate the needs and dynamics of any element of this coalition will inevitably adversely impact on all.

The Student

"This emphasis on learner-centeredness has implications for new, more flexible methods for students to access learning materials, methods which will increasingly be supported by communications and information technologies."

Napier University Strategic Plan 2002-2006

Ideally, the market should not be driven by technologies but rather end-user needs. Students want to learn; they want to broaden their horizons and they want to communicate. Simply put, they are today's investment capital; they are the means of future production and as such require access to the most effective and efficient learning available to further these objectives. E-learning, for the Business School, appears to fill the bill. It allows interactive, multimedia products and processes to be embedded in online learning environments such as Web CT and as such appears to allow strategic fluidity, particularly in relation to internationalisation, to develop (Figure 2).

Educational institutions are thus trying to provide their students (customers) with a single-point access to a range of course content, multimedia applications, and tools for asynchronous and real-time communication between students and tutors. The objective being the fabrication of a motivational and interactive environment geared to creatively engaging students in deeper and better learning (Gallagher, 1). However,

Encouraging independent learning is the backbone of e-learning. The institution is facing a situation that sees students having scheduling constraints that prohibit an over-reliance on time-dependent forms of education. It really does not matter whether these students are full-time undergraduate with part-time jobs or part-time or distance learning students with full-time jobs their needs are more similar than dissimilar. As Tony Bates of Canada's Open Learning Agency said, "There is an even greater myth that students in conventional institutions are engaged for the greater part of their time in meaningful, face-to-face interaction. The fact is that for both conventional and distance education students, by far the largest part of their studying is done alone, interacting with textbooks or other learning materials." The lesson to be taken from this is that e-learning is for all students not simply for distance or remote students and as such institutions should gear themselves to changing their attitude towards student needs.

At present the institution is developing the portal of Web CT and Web CT Vista (See Quote 3). Although, this is a vital communication and control component in itself it is deficient if it is not complemented with content and associated evaluation elements. To address this, the institution must not only provide the milieu through which ideas and solutions are generated but also materials that motivate students within an online classroom.

Students generally do not want nor do they care about the technologies behind the process. They do, however, expect their communications, information and services to allow them the flexibility to augment their personal learning profiles and modes of learning within the constraints of their life styles. These student demands are now placing an increasing burden and time demand on the lecturer.

If the institution achieves its strategy for e-learning then outcomes from this should be enhanced student retention, course completion, and overall enthusiasm for this innovative learning arena.

The Lecturer: Practical Experience Within A Business School

It is against this matrix of online learning that the lecturer strives to construct and develop inputs based on his own specialism. Over four academic teaching sessions the areas under examination were International Business and Strategic Management.

The empirical underpinning for this paper was two sets of questionnaires and semi-structured interviews undertaken with MBA/MSc students, full time, part time and distance learning over a two year period. The first questionnaire set covered case study use and effectiveness whilst the second addressed technology acceptance of the on-line, interactive system of instruction.

Students at their initial class session were provided with the portal to their course elements embedded in the institution's online matrix (see Figure 2). The objective for the lecturer, at its simplest level, was to create a paperless classroom. One where he did not have to spend hours beforehand photocopying handouts which he had forgotten to send to the print room. More esoteric was the objective of developing asynchronous and real-time communication between students and tutor where overtly the process of learning was abrogated to the student. Covertly, the lecturer's application architecture itself guided the learning process (Gallagher, 2).

Application architecture is perhaps one of the most difficult and yet one of the most easily over-looked areas when developing on-line multimedia strategies.

Architecture both covertly and overtly supports, directs, and communicates with the user of an application. Yet all too often in our application's construction we fall into the trap of making assumptions which are often spurious, lacking in clarity in both what we are trying to achieve and what our target market is, and what is really required thereof.

Pedagogical content is fundamental to developing longevity in multimedia educational applications. All too often producers of such applications are captivated by the technology of the delivery system, producing sparkling, colourful presentations with little regard to their content. This, however, inevitably leads to a one-dimensional, ineffective, single use application. Multimedia is the singer not the song. It stands or falls on the quality of its content. It is a tool which when combined with the right content provides a teaching and learning vehicle that significantly contributes to the learning process.

Initially, the provision of online learning had the appeal of offering reducing class contact time between the lecturer and the student. It seemed to offer the student the ability to assess his/her progress through the embedded tests and quizzes. Furthermore, it allowed the student to access articles and case studies and associated flashcards with the ability to check their comprehension and direct them to appropriate theory if a problem were detected (Figure 3)

However, it soon became obvious to the lecturer that the provision of stand alone materials, at the minimum a bank of PowerPoint slides, and the provision of online support were not satisfying the wants and needs of the student body. Unfortunately, having surveyed the last two years' MBA classes it became apparent that the students were Power Pointed to death. Tufte (2003) rails against PowerPoint for diluting the sensible transfer of ideas between presenter and audience. Essentially, bullet points are fine but they need to be explained and the nuances and linkages drawn out. The conscientious lecturer does this but, it is all too easy to rely on the slide to provide the educational input rather than the more demanding discursive interchange within a classroom.

It became rapidly apparent that problems associated with online delivery manifested when cases studies were introduced (Figure 3). These highlighted the feeling that problems were inherent not in the case studies themselves but rather in the online teaching methodology. As Dede comments, "Although presentational approaches transmit material rapidly from source to student, this content often evaporates quickly from learners' minds. To be motivated to master concepts and skills, students need to see the connection between what they are learning and the rest of their lives and the mental models they already use…….most people don't know how to apply the abstract principles they memorized in school to real-world problems."

Case studies have no definitive solution. When trying to analyze a case study each person will arrive at his or her solution based on the intellectual and experiential baggage that they carry with them. Learning by doing; increased familiarisation with the application of analytical techniques and appreciation of their implications; exposure to a number and variety of cases and their solutions; will help hone analytical ability. Likewise, exposure to peer group solution generation and lecturer driven solutions will also enhance the learning process.

In other words, our students wanted a physical community through which to learn. The result for the lecturer was the adaptation of the delivery methodology stemming from the recognition of the need to teach in different ways, to become both an enabler and manager of student learning (Twigg, 2004). Although crystallisation of this came through the development of the case study interactive methodology it was apparent that its lessons were equally relevant to e-learning in general.

The test of a good 'lecture' lies with the instructor, the situation and setting. If the lecture produces an exciting and provocative learning experience for those participating in it then that is a good lecture.

Institutional e-learning strategy (Quote 4) was bounded by an institutionalised perception of online delivery but, practical application in the form of blended learning with its increased demands on lecturer resources became for the lecturer, the operating reality. Blended learning architecture demands more of the lecturer in that he has to develop the information systems, control systems and communication systems that are adaptive to the student body's needs. All of which had to be underpinned by content quality and robust architecture. Simply put quality learning requires quality knowledge objects. All too frequently obsolete materials and irrelevant examples are provided to students. E-learning demands architecture with embedded knowledge resources and repositories that are continually renewed and updated.

In seeking to achieve this electronic delivery the lecturer must produce not only the most effective and rewarding learning experience possible but also the most efficient. However, as Zawacki-Richter (2005), points out "A frequently encountered reason for the reserved attitude to media-based teaching is the high workload associated with it. Academic reputations on the road to a professorship are acquired more by publishing research results and attracting external funds than by good teaching. In contrast, 60% to 70% of the working hours of a member of the academic staff are taken up with teaching, without this being adequately appreciated in proportion. The motivation to invest even more work in teaching is at times correspondingly slight."

Lecturers may not have the motivation to devote the effort and time to climb the learning curves of the software packages and systems requirements to produce online, interactive deliverables if they are not perceived as route to academic advancement. This perception is dependant to a great extent upon the actions of the institution and its administrative systems. The reality is that WebCT augments and enriches the learning process but in itself is dependent on the lecturer for its efficacy.

The Institution

"We have identified the following as our main objectives for academic development in the planning period:

- to grow the university, and extend lifelong learning opportunities, through partnerships and flexible learning;

- to improve the quality of our academic activities and the support we provide to our students;

- to become more learner focussed;

- to develop new approaches to learning, teaching and assessment which will help us to widen access and support off-campus learning."

Napier University Strategic Plan 2002-2006

"If we anticipate a future where more students need more learning, there is only one way to meet this need without diminishing the quality of their learning experiences: we must change the way we deliver education."

Carol A Twigg

Efficiency -v- Effectiveness

"The exploitation of new technologies should make HEIs both more efficient and more effective."

Napier University Strategic Plan 2002-2006

The response of educational institutions (Quote 5) to the changing dynamics of their environment has manifested itself in two basic questions (Figure 4):

To some extent, the answers to these questions, lies in how the institution views its Production Possibility Curve. This curve (for this example is termed the education efficiency/effectiveness frontier curve) represents the frontier against which all institutions in the sector measure their performance.

Diagrammatically this may be shown (see Figure 5) as follows:

The shaded area shows the area the institution would like to move. If it moves horizontally towards the vertical axis its output will remain the same but its costs will diminish. It will in effect become more efficient. If it moves vertically towards the efficiency frontier its student base will increase whilst its costs remain the same. Thus the institution becomes more efficient as its unit costs are spread over a greater number of students.

Increasing output whilst decreasing costs (the shaded area) will in any combination lead to increased efficiency/effectiveness.

Drucker commented that "Management is doing things right, leadership is doing the right things." This might usefully, if a little bit tongue in cheek, be rewritten as Strategy is about doing the right things whilst Tactics is about doing things right.

In the case of the educational institution the two basic questions (Figure 6) may be re-written as:

However, no institution will ever be 100% efficient/effective. This is an ideal rather than a reality. No matter how hard an institution strives to achieve 100% efficiency/effectiveness there will always be room for improvement! Nevertheless, as a relative measure it does allow the institution to compare its performance with that of its competitors in the sector.

A further way of viewing this situation is to place the institution in an organisational efficiency and effectiveness matrix:

The vertical axis measures the institution's effectiveness (are we doing the right things?) whilst the horizontal axis measures the organisations efficiency (are we doing things right?) (Figure 7).

Matrix Segments

Low Efficiency\Low Effectiveness

In this segment the institution displays both low effectiveness and low efficiency (Figure 8) a situation whereby the institution would tend to withdraw its resources. It is from this position that we take the starting point in the analysis and from which a new strategic thrust must emerge.

Low Efficiency\ High Effectiveness

If the institution shows high effectiveness and low efficiency (Figure 9) this may be indicative that it is capable of becoming with attention, more efficient as it is clearly in the area of business in which the institution wishes to be.

Management may see this area of activity as one that they wish to engage in but have not as yet achieved a sufficiently high enough market penetration. Alternatively, it may be indicative of an area of activity in which they are not sufficiently well equipped to undertake and may have to reconsider their position in terms of staying and investing or divesting and reinvesting the revenue generated.

High Efficiency\Low Effectiveness

Where the unit is placed in the segment showing high efficiency but low effectiveness (Figure 10) this may mean that management may wish to withdraw from this area even though it is cost effective because it does not fit the vision of where they wish to take the institution. However, a positive contribution is being made and as such may not be withdrawn if alternative opportunities do not provide as high a return.

Free Cash Flow released from withdrawals or surplus to operational requirements for those units may be redirected to support the development of other opportunities. In this instance from increased efficiency gains e.g. increased student numbers but same resources levels.

High Efficiency\High Effectiveness

In this segment the institution is positioned as being both high on effectiveness and high on efficiency (Figure 11). A situation that the institution aspires and one whose attainment must be carefully planned. If achieved then it should be 'milked' to provide the resources to develop other opportunities identified by management.

If any institution finds itself in the lower left segment of the Figure whereby it displays both low efficiency and low effectiveness in terms of the organisation's overall strategy then it should be considered for disposal or repositioning (Figure 12). A situation in which one could expect government policy to kick in and threaten to redress the balance by changing management.

On the other hand should the institution find itself in the upper right segment where it is achieving high efficiency and high effectiveness it is probable that it will increase its reach as it attempts to enter new markets.

Institutional efficiency has at its core a cost structure that has approximately 80% of the costs of universities being direct costs; consequently, controlling these is a prime concern.

A simple example here might help clarify the influences that act upon strategy and strategic choice.

A decade ago the ratio of administrative staff to lecturing staff was 1:1. Today it is 2:1. If the institution were to increase its revenue by 10% by recruiting more students then profit would rise by 10%. The appeal of this option for the institution is that it is simply doing more of the same and lecturing staff are doing what they always did but with greater student numbers. Students however, are facing larger class sizes and greater competition for resources and lecturing staff time. If it were to reduce its costs by 10% it would increase its profit by 38%. Lecturing staff however, would again be facing increased work and effort.

"It will be important for us to ensure that appropriate levels of support are provided to our students to enable them to fulfil their potential. We will monitor our progress in doing so through the Student Retention Project, the Student Satisfaction Survey and internal academic audit."

Napier University Strategic Plan 2002-2006

A further constraint on the institution is that Government policy only allows it to recruit domestic students to the level of its previous year e.g. 12,000 in 2005. This capping does not apply to non-domestic students. So university strategy (Quote 6) is pressured into seeking non-domestic students to mitigate the effects of cascading retention figures.

However, it can absorb students from the EU in its second year and students from China and India in the third year. These students counteract the non-retention shortfall of UK students. Moreover, these overseas students pay a higher fee base. Diagrammatically, this may be represented as shown in Figure 13.

The institution has suffered a nominal loss in student retention of around 37% Decay Curve 1 (Figure 13) However, the influx of students from the EU has allowed the institution to move across to Decay Curve 2 (Figure 13) in the second year of its course with a nominal loss in retention of approximately 20%. This is reinforced at the beginning of third year, (Decay Curve 3, Figure 13) then a further tranche of students, predominantly from China and India, join the course allowing a retention loss rate of approximately 10%.

The Dean of Napier University Business School, George Stonehouse, commented that the greatest number of students, overwhelmingly domestic students, drop-out in the first year of their course (Figure 13:A). This figure is still high in second year but progressively diminishes over the remainder of the course. (Figure 13: B, C, D and E). Stonehouse's objective, increase the number of first year entry students selecting Napier University as their first choice to 60-70%, is to address A and B by identifying the causal factors for student drop-out. He discovered that only one-third of Napier University students made Napier University their first choice university. The remainder may have had Napier University as their reserve choice, which meant that when they entered first year they already had a perception of having failed once. This perception was compounded if the student was recruited through UCAS clearing. On the positive side he discovered that the academic attainment profile of those making Napier University their first choice was actually mirrored by both second preference and UCAS clearing students. So academic ability did not seem to be the issue.

The tactics employed by Stonehouse to achieve his objective of 60-70% of Napier University students selecting Napier as their first choice is predicated upon the creation of a virtuous circle where student retention is increased which is reflected in reputation and the ubiquitous education ranking, league tables which attracts more students with Napier as their first choice which leads to better retention.

The actions envisioned for achieving this objective are:

- No examinations in first semester of all years (diminish the perceived feeling of failure)

- Monitor attendance. Student feedback indicated that students prefer discipline in their studies. (Better lecture and tutorial attendance will lead to better performance – diminution of perceived failure.)

- Introduce a small piece of assessment early in the semester – multiple choice (reinforce success, pass-rate should be 90% plus – diminution of perceived failure).

- Institute formative assessment/submission of coursework (thereby avoiding student gross errors of judgement with correspondingly higher pass rate and diminution of perceived failure.)

It may be reasonable to assume therefore, that the institution faced with the dilemma of maintaining and enhancing its bottom line in accordance with market pressures would be unwilling to accept a reduction in its domestic student numbers especially, in light of subsequent government capping. However, the tactical actions taken to enhance retention may lead to a greater workload for staff e.g. formative marking with an increasing staff resistance as the perception is double marking. At the same time there would be recognition that value added lies with the higher paying overseas students. This market segment is directly influenced by league tables. Consequently, a university strategy of cost reduction through e-learning disseminated across all market segments, and through the enrolment of higher-value-added overseas students can only work if the domestic student retention is increased. If achieved the result would be a more profitable organisation based on a virtuous rather than vicious circle of attainment.

So, in terms of efficiency/effectiveness the institution can be placed in the first instance i.e. increasing shortfall in student retention and its reinforcement through subsequent capping in the LOW EFFICIENCY/LOW EFFECTIVENESS segment. However, with the introduction of increasingly high value added, non-domestic students the institution moves vertically towards the HIGH EFFICIENCY/LOW EFFECTIVENESS segment as its costs are spread over a greater volume of students. The question now however, is how does the institution enhance its effectiveness? Controlling efficiency is relatively transparent but controlling effectiveness is less so. The answer lies, to a great extent, in the quality of the product offering, its support and its associated longevity and these call for a different strategy from that employed in the navel gazing of internal efficiencies.

Strategy Implementation

The fundamental question for the institution, if online is the chosen option, is 'how can technology add value? The answer lies in the relationship between the areas of

- Efficiency,

- Effectiveness, and

- Reach

If we return to the case of University A (Figure 5) and reiterate the questions posed in Figure 4 the answer to both is probably no! University A (Figure 14) is not very efficient relative to its competitors – Universities E and H. It is neither doing the right things nor doing them right.

Furthermore, this highlights a further factor associated with the efficiency/effectiveness curve that is, that staff resistance increases the closer an institution drives towards the frontier. Simply put, face to face skills are not easily transferable to the online environment especially when they are driven by administrative necessity rather than market reality.

So what should University A do? How should it respond? If change is appropriate then in what direction should the university move?

It would seem appropriate for it to try and emulate E in Figure 13. However, strategically this might be redundant in that it is simply building on 'accepted' methodological practices that will probably lead to a catch-up strategy rather than a transgression strategy that leapfrogs its competition. Recourse to the urban myth of the traveller who stops a stranger and asks for directions only to be answered by "well, I wouldn't start from here" may help crystallise its choices and in particular the choice of the route to resolving its paradigm shift. Online learning may be the appropriate strategy to pursue. However, it is a strategy hedged with many pitfalls. As Dede comments, "…access to data does not automatically expand students' knowledge; the availability of information does not intrinsically create an internal framework of ideas that learners can use to interpret reality."

The education industry is vital to world growth. It is the backbone for all industrial effort and universal growth. Knowledge and learning are the prerequisites for the creation of future intellectual capital. Therefore, the institution recognised it is facing both a parochial and a global market (Quote 7) and must develop a strategy to accommodate both.

The key players however, are already abroad, seeing their market as a global rather than national or regional one and their course delivery is flexible, interactive, and online. According to Bersin & Associates the major changes in e-learning in 2005 were:

- e-learning has matured into a tool for training and informational resources

- training budgets increased, especially in leadership and management education

- e-learning has changed the economics of training

- training organisations are changing dramatically, and turning into learning services organisations

- e-learning expands well beyond courseware

- the learning management systems (LMS) market grows rapidly and starts to consolidate

However, there is a growing body of evidence that supports the case that e-learning, although one of the fastest growing services on the Internet today with revenues between 6 billion and 7 billion dollars (Bizreport, 2003) in 2003 and rising to in excess of 18 billion dollars in 2005 (IDC 2005) carries with it the problem, as Edwards points out, "that many students never complete their e-learning courses. Although there is significant variation among institutions - with some reporting course-completion rates of more than 80 percent and others finding that fewer than 50 percent of distance-education students finish their course...course-completion rates are often 10 to 20 percentage points higher in traditional courses than in distance offerings". This is a view supported by Earnhardt who also comments that: "completion rates for web-based courses tend to lag behind their traditional classroom counterparts, sometimes as much as 40%" (Phipps and Merisotis, 1999). So any strategy based on online delivery with its allure of mass markets and falling costs can only be sustained in the long run by achieving optimisation of efficiency, effectiveness and reach.

The institution, given the saturation of its home market, decided to move abroad. To this end it examined its geographically closed rivals to evaluate their market position (Figure 13). If, hypothetically, we were to place the institution on the education efficiency/effectiveness frontier curve at A we might find that, H one of its geographically closest competitors, though smaller in student numbers has developed an overseas 'masters' presence based on flexible, on-line delivery of its MBA and as such is 58% more efficient/effective. E on the other hand, the largest of all the institutions, is 217% more efficient/effective.

Clearly, other factors will contribute to the disparity between the education efficiency/effectiveness frontier positions of the institutions. But if A wants to compete then it must examine what allows H and E to be fundamentally more efficient and effective in their offerings to the market place and having done so develop a strategy that transgresses those of its competitors. If it does not do so then the warnings of Bonk may come to fruition in that the market will drive out poor performers rather than tolerating a series of differing levels of efficiency and effectiveness.

On April 24th 2005 the institution announced that it had entered a collaborative agreement to provide online degrees to students in five Chinese universities. A move supported by the Chinese Government with the aim of introducing five further Chinese universities each year for the next three years. However, the reality is that e-learning across national boundaries doesn't always work as smoothly as we'd like "Product standardisation can result in a product that does not entirely satisfy any customers. When companies first internationalise, they often offer their standard domestic product without adapting it for other countries, and suffer the consequences." Ghoshal and Bartlett.

The institution had already made first contact with overseas market having developed elementary market penetration of a number of foreign markets, notably Hong Kong (Quote 7).

"The main foci for our international activities are China/Hong Kong and Taiwan, Malaysia and Norway. Our strategy in south east Asia is based on opening recruitment and development offices in key markets (Beijing, China and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), and on developing alliances and partnerships with major university providers for local delivery of our programmes (e.g. Hong Kong University)."

Napier University Strategic Plan 2002-2006

In this case, where the institution had been involved overseas, it had now taken the step of increasing its reach by moving deeper into international involvement on to a more strategic alliance basis (see Figure 14). This in turn has exposed it to both a greater demand for involvement in these markets with its concomitant market knowledge requirements and a far greater strategic risk component.

"When customers in different countries want essentially the same type of product or service (or can be persuaded), opportunities arise to market a standardised product. Understanding which aspects of the product can be standardised and which should be customised is the key." Bartlett and Ghoshal. By diversifying the institution should find more growth opportunities outside the UK especially in emerging markets. The outcome from this may be that the institution investing internationally reduces not only its costs but also its economic risk cycle.

Here the domestic MBA undergoing revision, had been revised to be brought on-line, in compliance with university strategy. Students would be able to register, access course requirements, and receive coursework, quizzes and feedback on line whilst course materials would be supplied in wrap-around text format.

Adaptation of MBA provision was proposed and based on the Revised MBA Structure 2005 to be implemented in 2006 which noted that changes would:

- More fully meets the needs of the target market for the MBA programme which includes on-line provision for a new global market.

- Is more likely to result in a successful programme with increased student numbers thus helping achieve strategic objectives for the university.

- Allows us to put in place a structure which can be more readily adapted for the development of specialist MBA's.

- Is an intelligent response to the practical and resource difficulties associated with supervision of projects, likely to be exacerbated by the entry into global on-line provision.

Specialist MBA's

The removal of the current 30 credit Project module creates space within the Programme structure to incorporate specialist modules, allowing us to develop a range of specialist MBA's. This is another area of key market expansion. Currently Napier has received approximately £330,000 of ESF (European Social Fund) funding (matched) to support the development of MBA Programmes for such markets.

Ancillary advantages would also occur in that by dropping the project element from the MBA programme failure rates associated with language problems of overseas students, tasked to produce an individual, research based, piece of work will be negated and pass rates should increase. Likewise, the increasing trend in plagiarism that has manifested itself in MBA projects in recent times, will also be ameliorated. The result should be a far more attractive product for the overseas market. However, in the event, the dropping of the project element was opposed by lecturing staff and subsequently not approved.

It is possible to hypothesise that adaptation and market penetration call for a systemic approach to strategy where domestic characteristics are not subsumed by an expansionist strategy geared to overseas markets and the allure of high return on investment. In the case of the MBA home market perception of these changes e.g. project dropping, wrap-around texts, and focus on administration could easily be construed as a watering down and an inferior product offering and as such adversely affect the take-up rates in the domestic market. But more damaging is the claim by many online producers that their product is on-line. In reality they often only provide one leg of the tripartite user groups components - Institution (administration) as the sole driver and this cannot create repeat custom and longevity for without fully addressing the student and lecturer components it is a recipe for disaster in both the home and overseas markets when the efficacy of the claims are challenged by the reality of the offering.

Uncertainty, however, favours market leaders especially in young (overseas), fragmented markets facing turbulent economic conditions. It is possible therefore, to view these market adaptations as a precursor to developing further and deeper structural changes as opportunities unfold for the institution.

Conclusion

At one stroke it would appear that the university has solved its problems. It had committed to a new delivery programme based predominantly on non-domestic students which at first sight appears to hold out the allure of increasing ROI and which leads to both higher efficiency and effectiveness. However, a cautionary note must be sounded. In terms of the education efficiency/effectiveness curve, elements such as staff resistance will increase the closer the institution tries to move towards the frontier. Assuming old dogs will teach themselves new tricks is naïve in the extreme. Lecturers like students need support to develop. Likewise, technology is not static and the rate of change is ever increasing. The simple fact is that increased effectiveness and efficiency requires increased commitment, effort, and acceptance of change, the more so when a new online architecture is called into play and reach is extended. The danger from this is corresponding risks of strategic rigidity and vulnerability to disruption.

Providing students with an online environment does not guarantee they will use it effectively. Indeed it is becoming increasingly apparent that only a minority of students use anything beyond the basic course materials, while the majority will only interact with online environments immediately prior to formal deadlines. If anything, it was found that students on the Napier MBA e-learning course, having received the blended learning format, still demanded greater direction from the lecturer. In essence, they did not automatically take responsibility for managing their own learning programme. Furthermore, student contact did not materially diminish, if anything it increased.

Throughout this paper, the phrase 'pedagogic challenges' has been avoided. Generally, it is used to describe situations that arise in the course of learning, teaching and assessment and associated requirements for professional development. However, in this instance the pedagogic challenges have not been addressed directly as they would shift the focus too far from the issues of strategic choice and implementation of the online strategy. This choice – online learning – is predicated on a cause and effect relationship that at first sight has an appealing rationality but, which after careful consideration, may have its foundations embedded in sand. No matter how well the strategy is envisioned, if it is formulated on a top down basis there is little chance of successful operational implementation unless the operational level inputs are encouraged and developed. Likewise, implementation cannot succeed unless all involved in the use of online –administration, lecturer and student - are committed to it and supported in its application.

Drucker commented that: "There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all." Although it would be wrong to adhere fully to this observation nevertheless, experience of developing online materials has led to the flagging up of problems, particularly those associated with pedagogical issues that simple cost benefit analysis cannot detect or account for, no matter how efficient they are. It would be strategically wrong to implement an online strategy based on the delivery of flexible materials which are constructed and implemented predominantly from an administrative view point. If this is done the institution will indeed have a strategic system which communicates with both the student and the lecturer and controls their administration very efficiently but its focus will be product and process oriented not customer focused. Furthermore, if the content materials of its e-learning systems are not effective for achieving the set objectives the strategy fails. Stonehouse, in identifying retention as the tactical issue has in fact flagged up the strategic flaw of ignoring who the customer is and what that customer's demands are. Simply put, poor pedagogic materials and supporting architecture can only lead to customer dissatisfaction. Consequently, Mintzberg's observation may not be too far off the mark when applied to Business School online learning, when he said "ultimately, the term 'strategic planning' has proved to be an oxymoron."

By and large, universities have not yet begun to realize the full potential of e-learning to improve the quality of student learning, increase retention, and reduce the costs of instruction. The fear is that they see only in terms of return on investment and lose sight of the huge strategic impact of intangibles and intellectual capital measures.

Online delivery brings not only new opportunities, but also new challenges. Strategy will lead structure but it will be found that only those individuals and organizations with the flexibility of mind and body to change and adapt to the challenges have a chance of profiting by them and even then only if they see beyond the headline profit figure. As de Geus, 1997 puts it "strategy is something you do rather than something you have".

Bibliography

[1] A'Hearn, F.Et al, Industrial Coll of the Armed Forces Washington DC. 2004 Education Industry, Seminar Report 2004 Accessed February 2005. http://www.stormingmedia.us/73/7315/A731534.html

[2] Bartlett & Ghoshal: Transitional Management, 4th edition McGraw Hill, 2004

[3] Bartlett & Ghoshal Text, Cases, and Readings in Cross-Border Management, third edition, McGraw Hill

[4] Bates, T & Epper, R. Teaching Faculty How To Use Technology, Jossey Bass, 2000

[5] Bersin & Associates Webzine, January 2006, Accessed February 2006 http://www.efmd.org/html/Knowledge/publ_detail.asp?id=040929kicm&aid=050208nlfp&tid=3&ref=ind

[6] Bonk, C The Perfect E-Storm: emerging technology, enormous learner demand, enhanced pedagogy, and erased budgets The Observatory on Borderless Higher Education, 2004. Accessed, Jan. 2006. http://mypage.iu.edu/~cjbonk/part1.pdf

[7] Boone, J. Education Correspondent, The Financial Times Limited 2006 OECD identifies threat to attempts to boost graduate numbers Published: September 13 2006

[8] Dede, C. Distance Learning to Distributed Learning: Making the Transition by Learning & Leading with Technology, vol. 23 no. 7, pp. 25-30, copyright (c) 1996, ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education),

[9] de Geus, A. The Living Company, 1997, Harvard Business School Press

[10] Drucker, P. Accessed 10 October 2006 http://www.quotationspage.com/search.php3?Search=&startsearch=Search&Author=Drucker&C=mgm&C=motivate&C=classic&C=coles&C=poorc&C=lindsly

[11] Earnhardt, C.C. Air Force Inst of Tech Wright-Patterson AFB OH School of Engineering and Management, Cross-Sectional Study on the Factors that Influence E-Learning Course Completion Rates, http://www.stormingmedia.us/02/0235/A023524.html

[12] Master's thesis Aug 2002-Mar 2004 Report date March 2004: Cross-Sectional Study on the Factors that Influence E-Learning Course Completion Rates

[13] Edwards R & Flexible learning for adults. In G Foley (ed)

[14] Nicoll K Understanding adult education and training. St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen and Unwin. (2000)

[15] Gallagher, J. (1) Interactive Case Study Experiences Applied To The Managed Learning Environment, Internet Business Review, Vol. 1 Nov 2004

[16] Gallagher, J. (2) WebCT And The Managed Learning Environment: The Educational Institutions Future Or Merely A Lick And A Promise? The Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE) Washington, USA: November 2004

[17] Hall, D. and Saias, M.A. (1980) Strategy Follows Structure, Strategic management Journal 1(2): 149-163

[18] IDC. Analyse The Future, http://www.idc.com/ (2005) Accessed 01/23/2006

[19] Linezine.com (2000) LiNE Zine http://www.linezine.com/ Accessed 10/1/2005

[20] LOD: Outsourcing of Learning and Training An International Survey, SRI Consulting Business Intelligence, 2005

[21] Mathews, E. A.; Air Force Inst of Tech Wright-Patterson AFB OH School of Engineering and Management Masters Thesis March 2004: A Study of Course Design Factors that Influence E-Learning Course Completion Rates, http://www.stormingmedia.us/25/2513/A251324.html

[22] Milliken, F. J. Perceiving and interpreting environmental change: An examination of college administrators' interpretation of changing demographics. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 42-63 1990

[23] NLII Viewpoint, Fall/Winter 1997

[24] Phipps, Ronald A., What's the Difference? A Review of Contemporary Research

[25] Jamie P. Merisotis. on the Effectiveness of Distance Learning in Higher Education. Washington, DC: American Federation of Teachers and National Education Association 1999

[26] Phipps, R. A.; Assuring Quality in Distance Learning What's the Difference? Wellman, J. V.; A Review of Contemporary Research on the Effectiveness of Merisotis, J. P Distance Learning in Higher Education. Washington, DC: American Federation of Teachers and National Education Association 1997

[27] Tufte, E.R. 2003, The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint, Graphics Press LLC, Cheshire , Connecticut

[28] Twigg C. A. Using Asynchronous Learning in Redesign: Reaching and Retaining the At-Risk Student: JANL Volume 8, Issue 1 - February 2004

[29] Whittington, R. What is Strategy and Does it Matter? (1993) Routledge Series in Analytical Management

[30] Zawacki-Richter, O (2005) Online Faculty Support and Education Innovation – A Case Study, European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning http://www.eurodl.org/materials/contrib/2005/Zawacki_Richter.htm